New Armchaired & Dangerous: Cannibalism!

"It is the horrifying reminder that we are part of a food chain & that we are meat!"

Hey,

I’ve had cannibals on the mind. I wrote a wee essay about Hannibal earlier, and have actually just wrapped up watching the finale. The show ends in the most beautiful and tragic place. I don’t want to give away any spoilers: but all the unspoken things become very spoken.

And so maybe it was no surprise that the latest episode of Armchaired & Dangerous would focus on cannibalism. For a podcast about conspiracy theories, this is a bit of a left-turn — but to be honest, this was never going to be a podcast just about conspiracies. It’s Armchaired & Dangerous — and what’s more dangerous than a cannibal?

Listen here to Armchaired & Dangerous: Cannibalism

As usual, here is the companion newsletter to the podcast — where you can read about what my guests had to say. Sign up if you haven’t already:

For this episode, I interviewed a biologist Bill Schutt who wrote a book about animal cannibalism, and then zoomed (again) with Nico Claux, a man who used to eat people.

Enjoy.

David.

Cannibalism. The act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. When a human does it — it usually makes the news:

Amazingly, there are no laws against cannibalism in America — it’s legal. The catch is that it’s pretty much impossible to legally obtain body parts. But I think while most of us aren’t doing it… we do think about it. We can’t help it!

Cannibalism is cemented in our pop culture.

From fictional cannibals like Hannibal Lector to very real ones like Jeffrey Dahmer — we’re all weirdly drawn towards the idea of cannibalism. Of course cannibalism happens all the time in nature: it’s perfectly normal. Female praying mantis’ love to bite off their partner’s heads. Very nutritious.

But when it comes to humans, most of us don’t have a taste for it. Most of us.

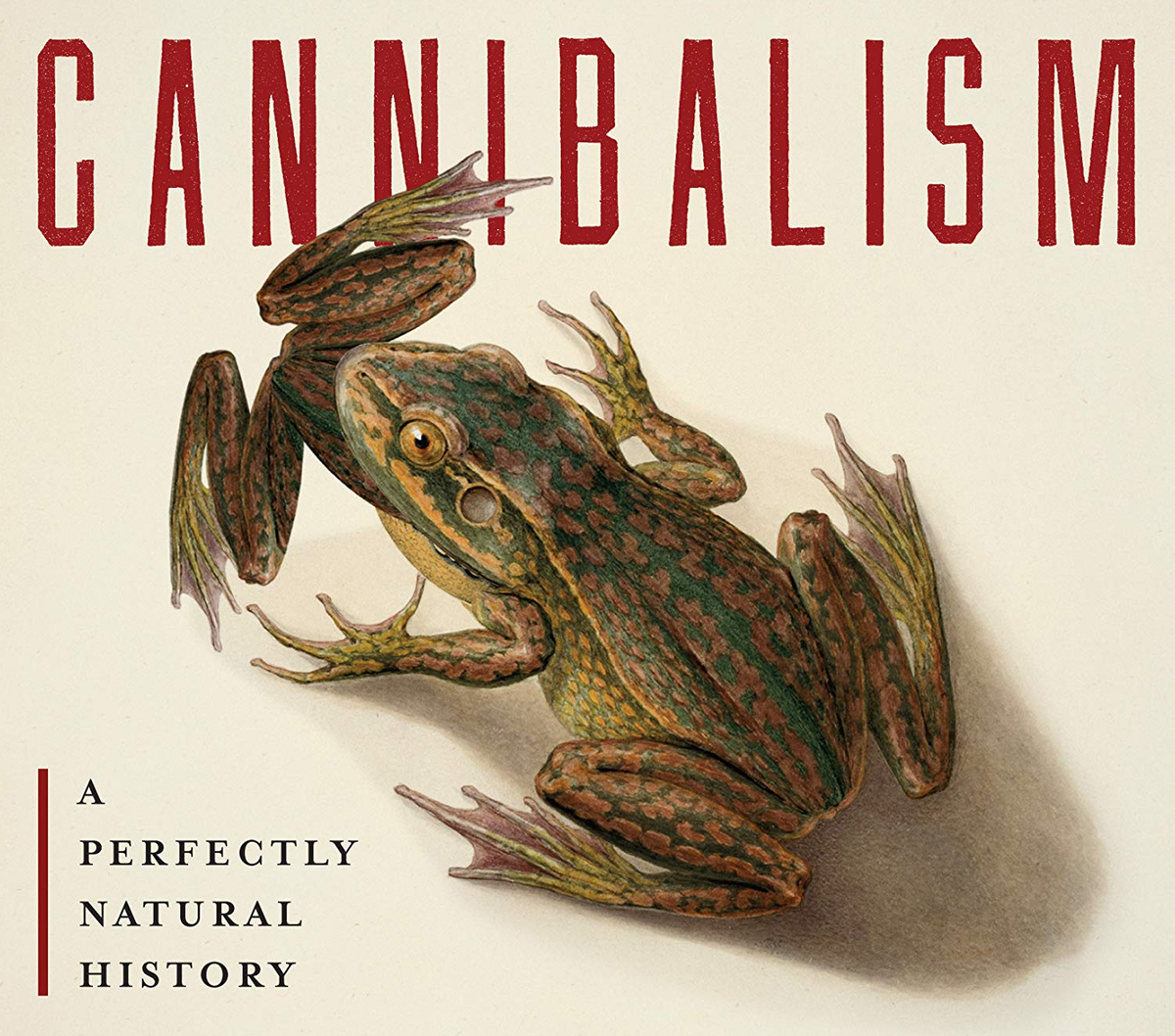

An interview with biologist Bill Schutt

Hi Bill. Now — a lot of your book, Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History, focusses on cannibalism in the animal kingdom. What surprised you the most when you dug into this topic?

The thing that was the most surprising was how widespread it was. When you think about animal cannibalism — even if you are not a scientist — you think of praying mantis’, or black widow spiders. But it was just so far beyond that in every group of animals you could think of!

Once you get into fish — all fish eat eggs or young of their own! It’s kind of like indiscriminate cannibalism: if you lay 5000 eggs or more and you’ve got these little things flying around. You aren’t going around going “oh that’s Jerry! That’s Sally!”

They are like raisins. It’s an easy way to get a meal.

If you’re a lion you take over a pride and there is a female with a cub you eat that cub — so you can mate with her quicker and pass on your genes! And it goes on and on.

And then there’s sand tiger sharks: they have in-utero cannibalism. So they lay eggs internally, they are inside the animal. And they develop at separate times. And there are two ova-ducts that a set of eggs develop in. And so on each side one shark is going to hatch first. And what it does is, it starts to eat the other eggs. And when they hatch, it eats the other sharks. And so at the end two sharks are born, they already know how to hunt. You have this sibling cannibalism — and to me, that was wild. Especially as these sharks live off the coast of New York where I live!

When it comes to humans eating other people, you talk about a few scenarios in your book. Like famous incidents where people are driven to cannibalism in disaster starvation scenarios. But I guess in general, why do some cultures consider it’s OK to eat people throughout history and others do not?

Culture is king, and it depends on where you are. If you are a member of the Wari’ in South America or the Fore in New Guinea, then you are raised to think that when your loved ones die, you consume them. And this has led to some serious health problems.

But when the anthropologists first got into South America and they met up with the Wari’ and went “oh wait what, you eat your dead?” and the Wari’ — of course this is paragraphing — went “what do you do with your dead?” and the anthropologists were like “well we bury them!” and they were like “are you out of your mind, how could you put your loved ones in the ground with the worms, why would you not incorporate them into yourself?” So it depends on where you are — and that is the main difference between animals and humans: we get to choose what is right and what is wrong.

Why is eating humans in the west considered bad?

This started with the Greeks! Homer and his pals chose cannibalism as a way to go “this is what the others do, this is what the bad people do. We would never do this!” and this snowballed. It went to the Romans, and from the Romans it went to Shakespeare and to the Brothers Grimm and Daniel Dafoe and Freud and the early anthropologists.

So you got this snowball effect, where what comes out of it is the knee-jerk reaction you and I have — or maybe not you — when we hear the word “cannibalism”. Like “oh my God it’s the worst thing in the world”.

It’s because it’s been engrained for thousands of years. It’s the ultimate taboo.

There is this amazing chapter in your book where you experience the form of cannibalism which is probably the only “acceptable” form of it in America. You meet a woman in Texas who takes mothers’ placentas and prepares them in some way so they can be consumed.

It was completely unexpected. The whole thing was surreal. I write fiction as well, and I don’t think I could have done a better job of putting together a bunch of really interesting characters, real sweethearts.

I was a JFK assassination buff and I had never been to Dallas before, so I went down to Dealey Plaza and there was a massive windstorm, so there was no power. And I go into a place and here is this guy in a chef’s hat and apron talking about going to Walmart to go pick up onions — as well as baby wipes to put down, so his wife could carve up this placenta!

So he was like “how do you want it? We can make it in a taco?” So I go into this liquor store in Texas and try and find the most Texas looking person I could find and told them I had to find a unique pairing for the evening! They basically ran away from me.

I mean this is the last vestiges of cannibalism — this is about what’s left of it. And if you consume your placenta after you give birth — there is this idea that somehow you will rebalance the hormones you lost when losing your placenta. So there is this thought that it cures the baby blues for example. But the person I worked with basically came out and admitted this was the placebo effect which is very powerful.

A conversation with Nico Claux - a (reformed) cannibal

When did you first became interested in this idea of cannibalism, or having this interest in dead humans?

When I was 12, I was at my uncle’s place and I saw a magazine — a French photo magazine. And in that magazine was an insert, six pages showing the victim of a cannibal case in Paris, by a man dubbed the Japanese cannibal. He had killed and eaten a dutch student in Paris. He had taken photos of the victim, and as a young kid I was fascinated by that magazine. I would peek and look through the pages.

A couple of years before that my grandfather had died under very difficult circumstances. It was after we played a badminton game — he had a stroke and one side of the family accused me of being the culprit. We went to the wake and it was the first time I saw a dead person in a casket. I had always been fascinated by graveyards and horror and that was the first time I was in a place where I was confronted with physical death.

So it was a weird cocktail that took place there a few years before I saw that magazine — maybe it was the genesis of it all, yeah.

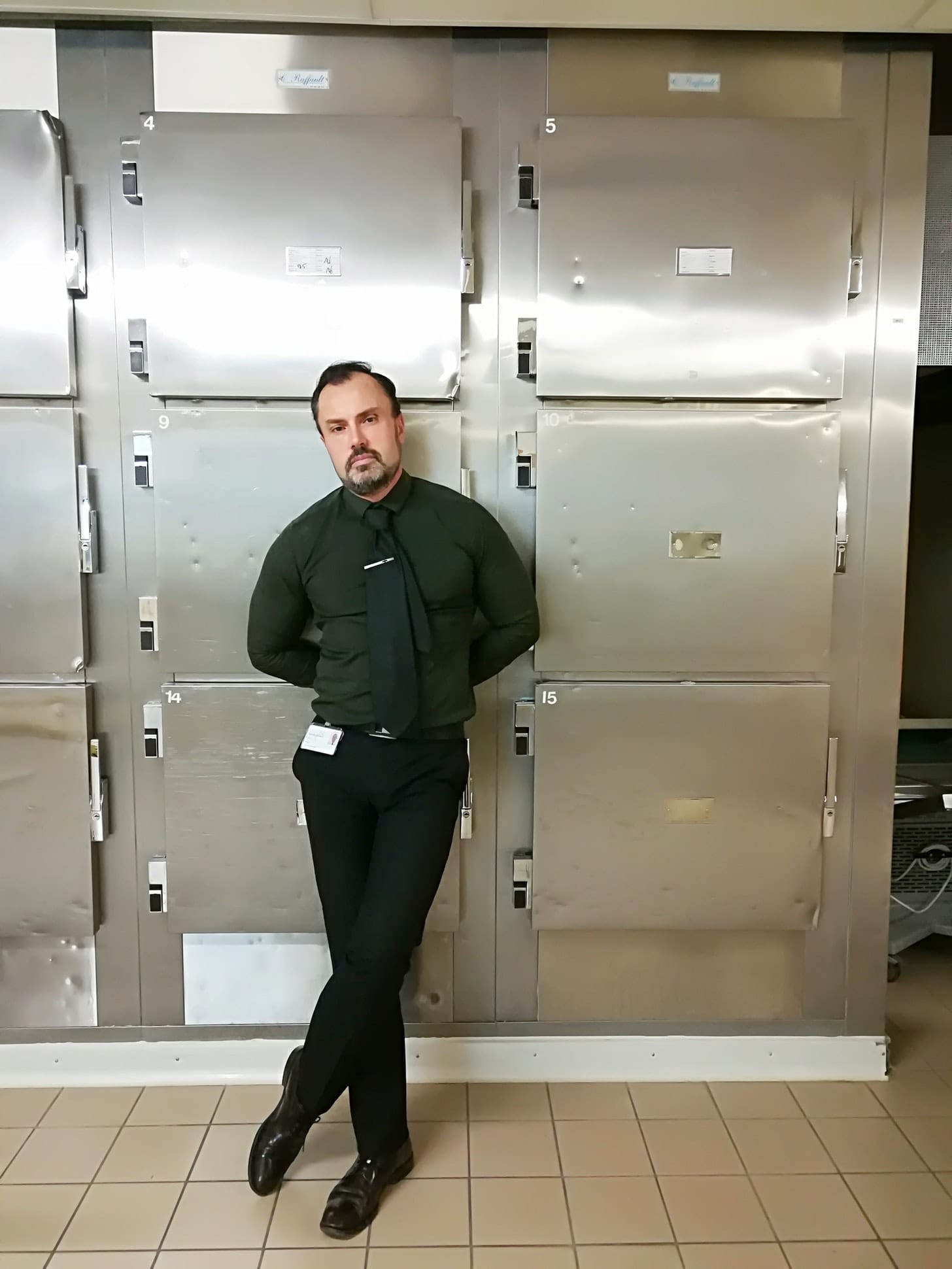

Okay, so at some point you ended up working in a morgue, is that right? How did that happen?

First I wanted to be an embalmer, because I thought the art of embalming was fascinating. I had read some books, but then I found out I had to study math and chemistry and I was not good at them at all. So I decided to look for an easier way in that industry. So back in the day, there was no internet, so I had no way of finding out where to apply. So I sent resumes. I was 19, I got a reply and I started to work in a morgue.

My first days in the morgue were quite chaotic. I had a lot of things to learn and they kind of want to make sure you are right for the job, so they make you watch autopsies and try to push you to the limits. But I really liked it.

I liked it the atmosphere, I liked that I was discovering a very unique job — and I also of course liked that I was working with actual dead people and participating in autopsies.

There is no specific course for being a morgue attendant, you learn everything by working there. First I was just a spectator, then I learned how to cut the cadavers open and how to stitch them up. How to help the doctor with the cuts — all those things when you are a morgue attendant. I learnt about the psychology of grief, you deal with families of the deceased. It was a lifelong — even if I was 19 — a lifelong dream come true!

When did you, er, begin the whole cannibalism thing?

The first time I was left alone in the morgue was during the weekends — so there were no autopsies. So I would try and focus on the job I had to do. Stay with the dead persons, study the marbling on the skin — the colours the skin would take, there are a lot of palettes of colours dead skin is taking.

And this is where I had the occasion — because it was a matter of jumping in — and this is when I would take strips I would cut from abdomen, before stitching the incision. So I my first choice I did was to swallow the flesh raw: it was an impulse. I was a in dark place back in those days — a lot of murder fantasies in me. I was constantly filling myself with horror films, death metal; years before that I had opened a few graves, gotten inside crypts. I did not have this moral barrier in me stopping me from doing these things, so for me it was a magical thing to do.

So I started to take strips of flesh and eat raw and over time I could bring little bits of flesh home, and cook them in several ways.

It was not something I would do regularly as we would only have two or three autopsies a week. I would be left alone with the corpse only one time out of three — so it was sporadically.

What would you cook it with?

I have tried several things. I have tried condiments, spices, which I did not like because I liked the taste of meat itself.

I really liked the act of chewing the meat and I liked it when it was still rare, when still a bit of blood inside. The more I cooked it the less I liked it.

What was the taste like?

Raw was — if you have had steak tartare, horse meat — that is the closest I would compare it to. But then I have read quite a lot on the subject that there are people during the great discoveries, Columbus, met several cannibal tribes and said in the Pacific Islands the flesh of the native would taste much sweeter and Europeans were the worst in how they tasted!

It was a matter of taste. I would never try offals or organs or liver. I could have, we had access to them, we even brought legs — I could have gotten flesh from legs but I always picked the meat from ribs and from the abdominal cavity.

You write a cookbook, too, right?

I wrote the Cannibal Cookbook in 2003 one year after getting out of prison — as a joke someone said I should write one, so I did.

I took it very seriously, read confessions from cannibals on how they ate the meat, and anthropology and how tribes cooked like Native American tribes or in the Fiji Islands, or in Europe they were practicing cannibalism and homo neanderthals were famously cannibals. We all have cannibal DNA deep inside! Of course the big moral issue — I am not going to debate that and it is not my role. And I am not the best one to talk about the moral issue of cannibalism. It was a funny book to write, and it gives actual advice, but of course don’t try this at home! Just for fun!

Why do you think people are so drawn to this topic — this awful topic of cannibalism? Like, why the hell am I talking to you now?

I think that the cannibal represents absolute horror and horror has always fascinated people. We have a tendency to slow down when accidents on highway. True crime has never been so popular —people love to be horrified! Horror is a natural form of entertainment. Reading about cannibals, you know it will never happen to you: it will happen in Russia or very far away!

It is also the horrifying reminder that we are part of a food chain and that we are meat!

We are just bones, sinews, meat and sometimes cannibal stories, they remind us of that!

Thanks, Nico. Yikes.

There you have it.

I hope you like this episode. I really am having a blast doing them — and the podcast wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for Webworm. So — thank you!

Bon appetite.

David.

PS: The tees are almost gone again — so get in quick. Tag me in them @davidfarrier when you get them — I love that they are going all over the planet! I wanna see them!