Ducking Out of Society With a Dumb Phone

Not everyone can afford to opt out of society for a month - or even a few days.

Hi,

I read through your feedback about my AI voice clone with both delight and horror — and am so appreciative to all of you who left comments.

There was such a wide range of discussion that it sort of blew my mind, from accessibility and ethics, to the very real issue of “AI fast tracking us to the climate apocalypse.”

I was also sent into an existential spiral when quite a few people thought one of the AI clones was me — and that it was way more natural than the real me. Even people that have known me IRL for over a decade fell into this camp.

I’m still spiralling.

Okay: From one contentious technological and societal issue to another.

If you’re anything like me, you’re aware of the outrageous amount of time we can spend staring at a smartphone — and if you forget, we have headline after headline reminding us how evil the devices are.

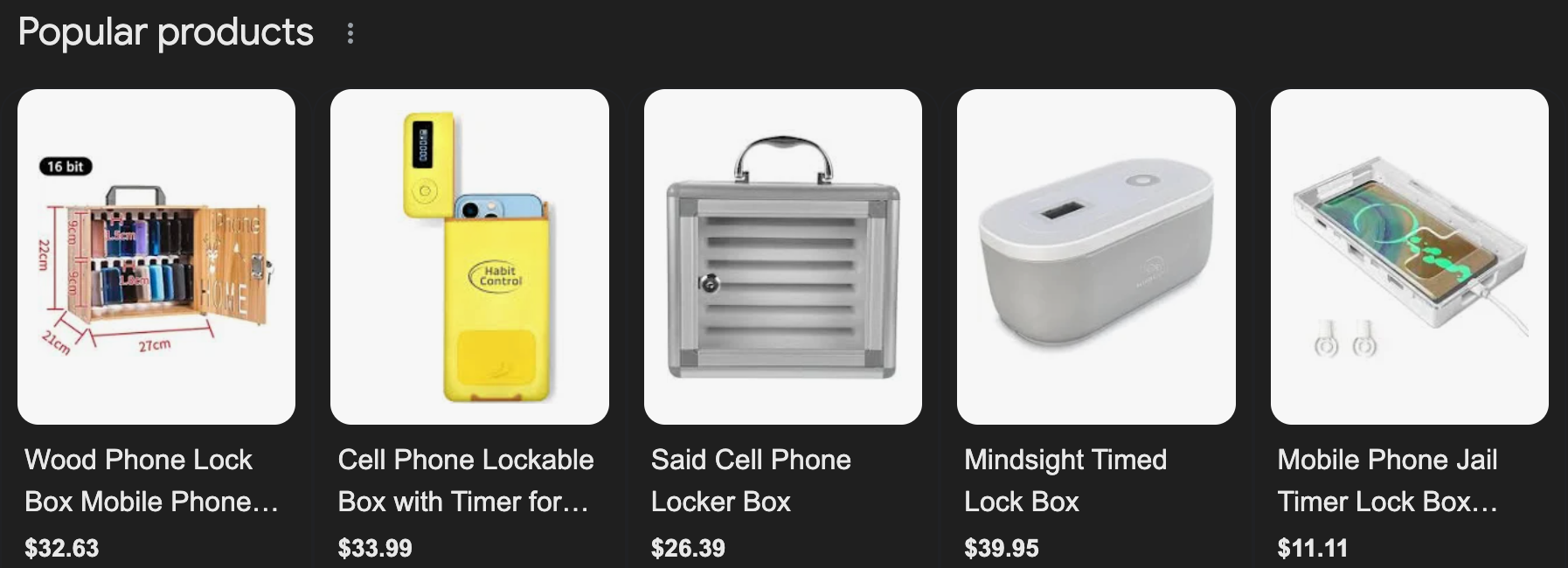

There are also about 1000 products that you can buy to lock your cellphone in a cage, a kind of chastity belt for those too horny for their phone.

I get it. Doom-scrolling sucks.

But at some point — it all starts to feel a little preachy, especially when Moby starts making black and white videos preaching the endless despair of cellphone use.

The conversation of course expands beyond cellphones — to gaming and apps and the culture at large — to the point where we now have incredibly reductive anti-tech arguments whizzing around, wishing for a return to more enlightened times.

Times when there wasn’t a cellphone in sight.

I’m being a bit extreme here to make a point, but also — I see Moby at least once a week walking the same hiking trail I walk… and every day he looks fucking miserable.

Today, I am very happy to bring you a guest essay on all this from one of my favourite writers, Elle Hunt. I’ve been nagging at her to write for Webworm for about three years now, but she kept getting distracted writing for the Guardian, the Observer, GQ, Vogue, Kinfolk, Vice, Slate, The Observer and New Scientist.

But finally, in a possible moment of madness, she wrote me a piece for Webworm.

David.

Are Bans, Laws and Dumb Devices The Answer? Probably Not.

by Elle Hunt.

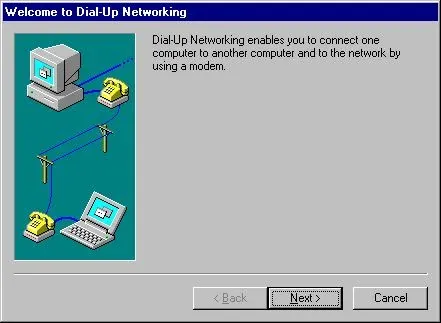

The other day I was chatting to a friend and made a throwaway comment about dial-up internet. Her face was blank. I persevered, imitating the screechy sound of the modem, the fractious daily back-and-forth you’d have with your parents about using the phone.

My friend is 26 years old. I’d never thought much of our age gap, but that ritual, it turned out, was before her time. I didn’t dare tell her that I used to check my bank balance by going into a phone box, and write down directions to my destination before I left the house.

If you, like me, remember a time before smartphones, you might sometimes feel wistful for the days when you weren’t quite so available. Yes, it’s an undeniable boon to be able to look up important information on the fly, keep in contact with friends and family, and do at least part of our jobs remotely.

But, after a decade, we are starting to reckon with the costs of this constant connectivity, and even to reach for solutions. Since the pandemic, which forced even more of our lives to migrate online, there’s been mounting concern about just how much time we spend looking at screens.

Sales of “dumbphones” — the kind with limited internet access, which those of us older than 30 will remember as once having been cutting-edge – are rising as people try to crack down on mindless scrolling, and make themselves less available.

Schools are increasingly implementing no-smartphone policies in the hopes of wresting back pupils’ attention.

The governments of both Australia and the UK have proposed introducing the legal “right to disconnect”, limiting employers’ freedoms to contact employees after hours. Australia is also looking to join several US states in banning young people from accessing social media.

It’s hard to escape the sense that – having made the internet all but essential to every aspect of life – we’re now trying to wrestle the genie back into the bottle. But I can’t help but feel that not only are all these measures unlikely to tackle the problems we’ve identified with our reliance on tech, they risk creating more.

This year, these concerns have coalesced around The Anxious Generation, a new book by the American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt claiming that the mental-health crisis among young people stems from their use of social media. Experts have poked holes in Haidt’s argument, pointing out that there’s limited evidence for a causal link. (The podcast If Books Could Kill gives a good précis of its flaws.)

Similar flaws have been found with Stolen Focus, Johann Hari’s bestseller about the tech-driven “breakdown of humankind’s ability to pay attention”. It may ring true with our experience of being constantly distracted by our pinging phones, but in truth we have limited insight into how humans were able to concentrate in the past. If we’re feeling stretched thin, it might be that we’re simply asking too much of our brains.

But the momentum behind both books, driven by parents, educators and policymakers, is at least proof of emerging moral panic about our devices, and their perceived negative impact on our wellbeing. The question is what we can feasibly do about it without creating yet another divide in our already highly unequal societies: between those who can afford to disconnect, and those who can’t.

Haidt’s recommendations are commonsense, if difficult to implement at scale: limiting young people’s access to smartphones and social media, and increasing their offline independence, responsibility and opportunities to play. But Hari’s conclusion is to call for a societal “movement to reclaim our minds”, following his own experience of a months-long “digital detox” on Cape Cod.

Needless to say: not everyone can afford to duck out of society for a month, or even a few days. It also doesn’t address the question of how to protect your newly-reclaimed mind upon your re-entry to our hyper-connected society. Implementing a tech blackout for teens, meanwhile, seems like it would take time and resources beyond many working parents and teachers, already stretched thin.

Both responses underscore our eagerness for an external solution to the apparently noxious effect of our devices: a law that says we can ignore that 8pm email from our boss, or a phone that shields us from notifications by simply not being able to host apps. But such measures can only achieve so much when our personal and professional lives rely on us being connected.

Not only that: they gloss over the practical difficulties and even costs of logging off. It’s one thing to claim that a “right to disconnect” law will protect workers from being penalised for non-replies; it’s another thing to feel secure enough in your employment to let an urgent email slide.

Likewise, I was surprised to learn that my Gen-Z friend had spent most of her teens with only a Nokia “brick” phone before it became more of a hindrance in her life than a help. Without web access on the go, she was overly reliant on the kindness of strangers; she also struggled to access her university email and other essential services.

When I tried out one of the new “distraction-free” smartphones a couple of years ago, I found it similarly untenable. Yes, it could send and receive texts, and make calls – but most of my correspondence is conducted via WhatsApp, leaving me with the choice of either attempting to redirect all my contacts, or else laboriously switching between devices.

Ultimately, as much as we might like to point the finger at tech and imagine we’d be better off without it, we are entirely in charge of how we use it, and how much we let it derail us day-to-day.

Instead of reaching for bans, laws and new, “dumb” devices to address the problems we’re experiencing with our online lives, it seems to me that we need to give ourselves more credit, and bolster our sense of autonomy.

Deleting TikTok or Instagram or X might give you more time. But it’s still down to you to figure out how to spend it.

-Elle Hunt.

Elle Hunt lives somewhere in England plagued with two alien creatures that demand most of her attention (when she’s not on her phone). You can read more of her work here, and hopefully more on Webworm in the future.

PS: There’s a new episode of Flightless Bird out today, and it’s about the history of slime. I talk to my friend professor Christopher Michlig, a guy who thinks way too much about slime and its place in our culture.