Letting The Chaos Speak For Itself

Gonzo journalism, "The Department of Information", and the art of just letting people speak.

Hi,

First things first: Back in May, I interviewed my friend Louis Theroux about his “Jiggle Jiggle” rap that had found a new viral life, thanks to TikTok.

Well, this week American singer Jason Derulo went all in — recording a song and releasing this video with Louis that gives a certain polish to the ridiculous rap that originated on Louis’ Weird Weekends back in 2000.

I think it’s a fun watch to end the week. And Louis’ line about chicken nuggets really destroyed me.

I think it’s fair to say I digest a lot of media in my life — a lot of news, a lot of social media, a lot of documentaries, and a lot of journalism.

Being from New Zealand gives you a slightly interesting take on things too, because New Zealand is such a quirky little mess in the media landscape, and it paints how I see everything else.

Watching the trailer for Discovery’s Armie Hammer documentary — House of Hammer — I couldn’t help but think “You could never make this in New Zealand.” The film is essentially a string of defamatory statements about Armie Hammer. The film shoots the allegedly incredibly abusive Hammer down in flames.

See how I threw an “allegedly” in there? That’s a knee-jerk reaction to practicing journalism in New Zealand. Our defamation laws are so incredibly tight, it’s incredibly difficult to “out” anyone in any public way before their guilt has been decided in a court of law. It’s why reporting Arise is so incredibly difficult. Sure — I said a lot on Webworm, but believe me when I say that I couldn’t say it all.

The simple fact is, I could not have made Tickled if David D’Amato lived in New Zealand. Too many things that I said would have been considered defamatory, and the film would have been cut down by lawyers into a thin flakey crisp. The Hammer documentary? You’d have to throw it in the bin. Nothing would be left.

If you’re a bad man doing bad things — come do them in New Zealand.

Another great advantage of living in New Zealand is that if you get a job in the media, you can borrow someone else’s story and pretend it’s your own.

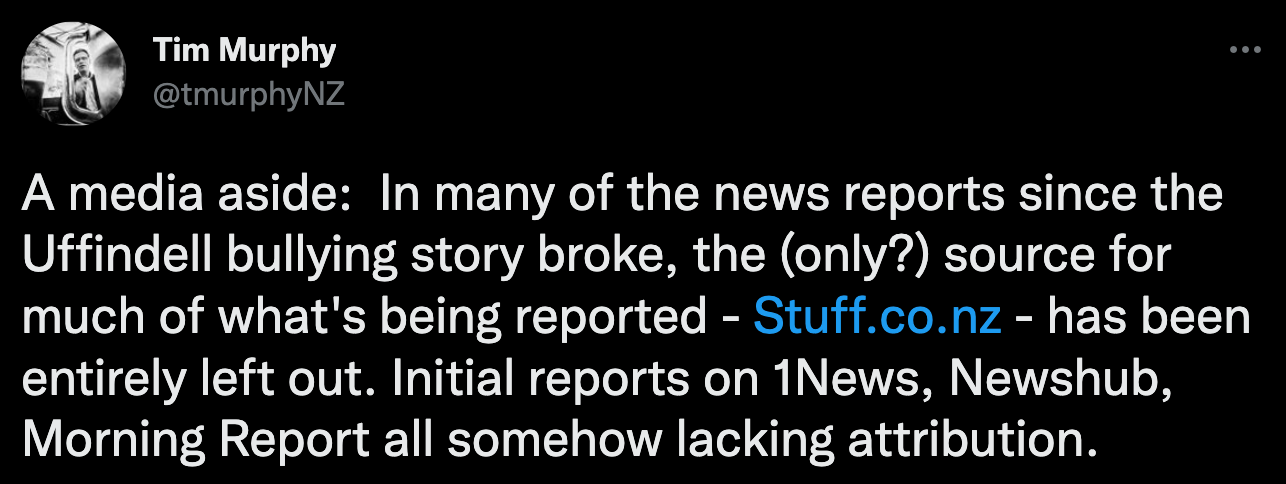

I experienced this very clearly with all of Webworm’s Arise megachurch reporting. In ‘The Incredible Multiverse of NZ Journalism’, I looked at how I’d report something, only to have other organisations report the same thing with zero mention of the original stories.

New Zealand has a strange phobia of crediting other people’s legwork, something that is common in the likes of the US.

There was another great example of this this week, as Stuff journalist Kirsty Johnston broke a story about a member of parliament’s antics back when he attended school, which included viciously beating a younger student in the middle of the night.

What made this particular story grating was that the MP — National’s Sam Uffindell (a privileged idiot) — is big on crime and punishment.

It was an incredible story that was complicated to tell. Complicated for Kirsty, that is. It was much less complicated for most of New Zealand’s major news outlets who simply parroted the story while refusing to mention Stuff or, God Forbid, Kirsty Johnston.

I really hope this changes at some point. It’s OK to acknowledge other people’s work. It doesn’t detract from your own.

The Department of Information.

The main thing I wanted to share as we head into the weekend is a small team of New Zealanders who are doing really fascinating journalism work: The Department of Information.

If you’re a New Zealander reading this: It’s a great insight into parts of kiwi culture you won’t see anywhere else, or that you certainly won’t see told like this.

If you aren’t from New Zealand — and just associate it with Lord of the Rings and Flight of the Conchords — it’s a good slap in the face.

I was introduced to this outfit by Tony Stamp, who writes the monthly ‘Totally Normal’ columns here on Webworm. And I’ve been transfixed ever since.

I guess you could liken it to Channel 5 News, Andrew Callaghan’s wild gonzo YouTube channel tunneling into the seedier sides of American culture. Just delete the Americans, and insert some New Zealanders instead.

They create short documentaries and throw them on YouTube and Instagram. There is no commentary at all — they just let the subjects talk and share their point of view, no matter how pure or abhorrent that view may be. From what I can tell, the only editorialising or point of view from the filmmakers is the old let-them-hang-themselves-by-their-own-words thing.

In a way, it’s the opposite of what I do: There is little in the way of context or fact-checking. It’s just a certain scene left to speak for itself. The viewer is left to make up their own mind about what they think of it all.

The end result is just being thrown headfirst into some fairly visceral, maddening, and sometimes comical situations. The first video that drew me in was this piece on New Zealand’s underground car racing culture (and in case you’re watching this at work or in front of the kids — there’s plenty of chaotic language, so maybe pop the headphones on):

Another favourite of mine — their exploration into an abandoned water park, “ruined by a Russian millionaire”:

I wanted to find out who was behind this stuff — so I reached out to them to get some insight into their intent, mindset and motivation.

So this is Gryffin, Louis and Noah talking on what the Department of Information is all about.

I’ve been loving your videos for some time now, and found myself infinitely curious about who The Department of Information is. Who are you? What do you all do when not making this stuff? Who is in the team?

GRYFFIN: We’re three mates who decided last year to start making short films telling stories about people and places we find compelling. We’re all doing different creative degrees at uni - Noah studies film, Louis studies design and politics, and I study fine arts. Between the three of us we have a mix of skills that comes through in all the research, filming, animating and editing for the films. When we’re not working on the Department of Information, Noah’s normally helping out on film sets, Louis is writing essays and I’m curating art exhibitions.

LOUIS: Yeah, we just wanted to learn how to make videos. We bought a camera and because that was so expensive, we realised we had no choice other than to start making videos properly. So, without much of a plan, we turned up to an anti-vax protest in Auckland and hoped we could make a good video talking to people there. That’s where it started really.

NOAH: After we’d finished our first video, we were struggling to find a name for the channel. Our group chat with some friends was called the Department of Information, so we copied the name from there. We find it funny getting letters and emails addressed to the Department of Information.

What would you say is your main aim with your documentaries? What are you trying to show?

NOAH: We’re trying to show groups and people you don’t normally hear from, even if it’s a bit uncomfortable. We normally don’t narrate much or ask many questions to try and make it more immersive. In the Dunedin video we also interviewed the Mayor but he felt quite removed from the students and their culture so we cut it out. We’re also not a mainstream outlet so we don’t have to add a disclaimer or rebuttal every time someone says a lie or contradiction.

We let them say whatever they want, without challenge, and the audience can make up their minds for themselves — although sometimes our editing does give a hint about our own opinions. It’s strange but kind of satisfying when opposing groups will both say they enjoyed the video, but then argue in the comments with each other. There’s one big anti-vax and anti-1080 subscriber in particular who always comments to say they like our work. I think you can get along in some way with almost anyone if you listen to them and give them respect.

LOUIS: Yeah, also it's all just stuff we find interesting and would want to watch ourselves. After the first few videos, there was a point where we realised we probably wouldn’t watch some of them voluntarily. That was kind of nice because since then all of the videos have had a lot more focus on what we find interesting and what each of us actually want to make. If we find it interesting, then hopefully others will too.

Is this all a labour of love so far? Is anyone financing things?

LOUIS: Kind of. We’ve made about 40 cents from YouTube so far. But we were pretty lucky early on. Re: News, who are like a youth-based platform for TVNZ, messaged us after our first video. So, we’ve had an agreement for most of this year where we sell them shorter versions of our videos and we get to keep full freedom on our YouTube channel. It works out pretty well, because it gives us a bit more money to travel around NZ and we can learn from people at TVNZ who know journalism way better than us.

To me it feels like there is an influence of a new sort of journalism coming through here, which is also probably a throwback in a way, too — but to the likes of Channel 5 out of the US. What would you say your influences are? I mean, mine are clearly Louis Theroux, which is a very different sort of documentary work!

LOUIS: Uhhh, there are lots. Clearly Channel 5 and that kind of style. But then also a range of other internet-based journalism. YouTube offers so much range and diversity in how people approach interviewing and storytelling. You have guys like Nardwuar who talk to the same musicians that Chicken Shop Date does, but they do it in such different ways. I guess having so much competition is good, it means people have to find their own style and niche. I like that a lot.

NOAH: I think we are actually influenced by Louis Theroux in a way because he was a big influence on Andrew Callaghan from Channel 5. Iman Amrani’s series on masculinity, and especially the episode on Jordan Peterson, is great — it was one of the first times I saw someone engage in a genuine way with people they didn’t always agree with. Other influences: rapid tone shifts in UK comedies like The Office, the strange vibe of The Armando Iannucci show, and how Paul Thomas Anderson creates unusual contrasts with music.

GRYFFIN: I think my main influence would be the classic vice videos of real gung ho journalism where a few people with a couple cameras find themselves in really crazy, viscerally real situations. But I also love people like Tacita Dean, Christian Marclay, Joel Haver and David Lynch for the kind of beautifully surreal films they make. I really like the idea of being able to combine elements of journalism, humour and beauty to create films which are both entertaining and provoking.

Your street racing video is just so surprising and visceral: Can you talk a little bit about making that video, as I am curious about what your approach is to going into some quite unhinged situations.

LOUIS: I actually don’t think we had much of a formal approach for that video. The first two car meets (both in Auckland) were really organised and friendly, so it was just a matter of going up and talking to people. But for the skid meet, we had no clue what to expect. We pretty much set off for Hamilton hoping that we would find an event with lots of people and lots of action.

After driving for an hour, we arrived at a small self-serve petrol station on the edge of the city. It felt so otherworldly. Every pump had three modded cars parked on it and there was this constant smoke lingering above everyone. It took us fifteen minutes to even build up the confidence to go over and say “hi”.

Everything was just so different to the Auckland meets. Most of the guys were probably in their mid-20s, while the girls looked fresh out of high school and a lot of the others had kids waiting in the car. I think from there we kind of realised that we were going to get a good story, so it was just a matter of following the convoy until we found something. Most of the spots we stopped at were on the side of the highway and would immediately clear off after the police arrived. But yeah, all three of us were pretty on edge most of the time.

At the last spot, it felt pretty anarchic. The crowd was just getting closer and closer to the skids as they got drunker. There’s a few shots we didn’t include where you can see me jumping backwards because I thought someone had been hit.

Honestly though, I think our approach worked out well in the end, because we had no real formality and people didn’t seem threatened by us pointing a camera in their face and asking questions.

What I find really great about your work is how open people are to talking to you. Was that surprising to you also?

NOAH: I hadn’t really thought about that. Normally when someone’s opening up, I’m just relieved we’re going to get some decent stuff for a video. I think people just want to be heard and often we’re speaking to people who can’t tell their stories anywhere else. When we spoke to the guys running the anti-1080 movement, one of them was really reluctant at first. But once we’d had a cup of tea off-camera and he realised we weren’t going to be attacking him and trying to beat him in a debate he opened up.

That also comes from not asking many questions and leaving pauses — we stole that from Louis Theroux and Andrew Callaghan. People aren’t used to getting to say whatever they want for however long they want, and I think that encourages them to just keep talking and bring out some deeper stuff. We can say we’re an independent YouTube channel and that helps a lot too — I don’t think we’d have got good access at places like the drag races or antivax protests if we were working for a mainstream outlet.

One of your films felt different — the kōkako hunt with Rhys Buckingham. It felt quiet, and really sweet. Tell me a bit about your approach to shooting this story, and how it is filming something so quiet with one man, as opposed to the chaos of your other videos?

GRYFFIN: This film was a really special one for us. While the chaotic videos can be very entertaining we are also interested in telling intimate stories like his. We spent a couple of days in the bush with this guy Rhys and developed a true appreciation of his search for the kōkako. We ate meals together, slept in the little DOC hut together, hiked together and so on.

He has found a real purpose in life, a quiet passion that keeps pulling him back to the forests which I found really compelling. In the film I really wanted to capture that feeling of being at peace in the bush amongst the birds, so I hope that comes across in the final edit. We have some upcoming films we’ve shot which have a similar feel to the kōkako where we spend a decent amount of time getting to know the person or community which will be a kind of calm break between our higher energy content.

What do you think of New Zealand journalism at the moment? Who do you admire? Or not?

LOUIS: That’s an interesting question actually. The main reason we started the channel was because me and Noah were volunteering at the student radio station, reporting on pretty standard local and national stories. It felt like not many people our age were listening to us. Last week, we were looking back at old news archive footage and all three of us kept talking about how the issues and their presentation hadn’t changed at all.

I mean yeah, it's obviously important to maintain good, formal local journalism, but I think more and more it feels like people don’t care. Also, I think New Zealand journalism is still made for older, educated, upper middle-class people. I’m not sure if most people really feel represented by RNZ or Newshub or whatever. I guess it's hard for mainstream media to find a balance when there’s so much shit going on and it’s easier for people to watch news that’s exciting but ultimately not very important.

NOAH: Yeah, bFM was great and taught us heaps but we’d only ever be talking to politicians or spokespeople who were media trained. I had a weekly interview with Christopher Luxon and it was really good practice – but there’s a limit to what you can get out from someone who’s kind of just reading off bullet points. One of the biggest things that pushed us to make the channel was after John Campbell gave a talk to the news team at bFM. He told us to start speaking to people actually affected by issues rather than the people who say they represent them.

I think tonally what you do is quite extraordinary. There are a few moments in that Dunedin Student piece that hit you in the stomach — like the kid that's just so suddenly angry he'll never own his own home. How do you ride this balance of humour and more poignant, impactful moments?

NOAH: Thanks, that’s really kind. When we’re looking for stories, we’re looking for something controversial or funny, but something that also has a deeper aspect to it. Ideally a viewer goes into a video prepared to laugh at someone but comes out with a bit more empathy towards them. The first video we made — on antivax and anti-government protests — set the tone for a lot of what we do.

The first draft was pretty much just every funny clip in a row but when we showed it to some friends they said they felt exhausted watching it. We decided to add in some interludes, and then put in some deeper, emotional moments towards the end. We’ve had those same couple of friends review all our first drafts since them. We’ll video call and see if they laugh or sound disturbed at the right points, and if they don’t we change it.

Going on the sorts of stories you explore — what do you think of the state of Aotearoa right now? How’s it doing? Because honestly I feel like you are slam bang in the middle of so many things and might have some thoughts worth sharing.

NOAH: I think we all live pretty sheltered middle-class university lives so our videos help us get out of that bubble. Talking to people with different worldviews doesn’t really make me optimistic that everything will turn out well. But at least I know that most people have genuine intentions. There’s lots of things that frustrate me about NZ and its politics and everything else but I try not to think about them too much. Making the videos has helped channel that frustration too.

LOUIS: Yeah, I generally agree with Noah. I think also there are almost two different New Zealands coexisting at the moment. The majority, which we’re probably part of, are all modernising and kind of fitting in with what’s happening globally. But also there are so many people, especially rurally, who still want to and are living the gumboot wearing, small community type lifestyle and aren’t so keen on a lot of the modernisation stuff. Talking to guys like Rhys or the anti-1080 protesters was really interesting in showing that divide.

GRYFFIN: I think we’re experiencing a pretty tumultuous time broadly speaking and with that comes a lot of confusion and anxiety. The amount of information we’re exposed to on a daily basis when it comes to the state of New Zealand and the world at large can be overwhelming - which is why going out and talking to people living in different ways and holding different opinions has been really valuable. It’s somehow very comforting to see the subcultures and alternate ways of constructing meaning in the world which make up New Zealand, which is why I think it's important to be telling these stories.

What are your plans with Dept of Information in the long term? Are there any?

LOUIS: Become really rich and start a multinational media empire with offices all around the world. Nah, I’m not really sure. It’s pretty confusing to plan that far ahead with each of us still studying. Hopefully just keep making videos that we find interesting and that show parts of New Zealand in a different light. It’s such a strange country. But yeah, maybe we will start doing more things overseas when some of us move abroad in the next few years. That could be pretty sick I reckon. But who knows, we could also fall out, hate each other, and the channel will disappear by the end of the year.

NOAH: I’m probably moving to the UK next year so the channel will have stories from both NZ and Europe. We’ll get some people to help us out but the main ideas and editing will still just be us three I think. I also really want to do a video with Kim Dotcom, so if anyone knows how to contact him please let us know.

GRYFFIN: I’m also considering moving to Europe next year for post-grad study in fine arts so the DOI intros might get all weird and experimental. We are all pretty motivated to make really interesting films, so whilst the type of stories we tell might change I think we are all in it for the long haul.

David here again. I like them.

They’re smart, and this thing they said is just so incredibly key to interviewing someone: “Leaving pauses — we stole that from Louis Theroux and Andrew Callaghan. People aren’t used to getting to say whatever they want for however long they want, and I think that encourages them to just keep talking and bring out some deeper stuff.”

It’s incredibly hard to do. I am terrible at it. As humans, we’ve learnt to avoid awkwardness by filling in gaps. But in journalism and documentary, if you’re talking… they’re not. And that means you can be missing out on some really good stuff. That’s not to say you shouldn’t put people at ease — but you’ve also got to learn to shut your trap sometimes. Let them fill the gap.

As is probably clear by now, I really like DOI’s stuff — and I wanted to link to one other piece that’s very much up Webworm’s alley, as they interview a number of New Zealanders sucked down the conspiracy rabbit hole:

At about three minutes in, a protester starts praising the virtues of Alex Jones, who’s recently been in court for spreading horrific disinformation that the victim’s of school shootings were all actors.

Thinking about Alex Jones is interesting — because a documentary about him has just been released called Alex’s War. It’s interesting because it’s made with a similar ethos to what Channel 5 and the Department of Information are doing: Just letting the subject speak, with no analysis, fact-checking or criticism.

In the case of Alex’s War, I find it kinda repugnant — as Jones is allowed to present his view of the world, unfiltered: A world where he says he had very little to do with spreading the lie that kids didn’t die at Sandy Hook, for example. The idea, as stated by the filmmakers, is that audiences are not idiots, and they can make up their own minds about whether to believe what they’re hearing. Which is true. It’s what I’ve been saying in this newsletter.

The problem is — Alex Jones already has an audience of millions, who he’s now hawking this documentary at. An audience who will swallow his ideas hook, line and sinker. And there’s something sort of awful about that.

But the characters found in Channel 5 and the Department of Information tend not to have an existing following in the tens of millions. I think that’s a subtle difference worth noting, at least for me.

I’m curious what you make of this type of gonzo journalism. Just letting the chaos speak for itself. I just get excited that some young upstarts are going out there and telling stories — stories that can be hard to watch. Hard, and sad, and terrible, and sometimes funny.

Just like real life.

David.

My main issue with this piece is that now I really want to watch these vids, but it's 630am in New Zealand, I don't want to wake my partner or the cat up by blasting sound and it's too bloody cold to get out of bed to get my head phones. Very problematic David.

Great article :)

Leaving those pauses is a skill I learned at uni when I was becoming a teacher. I learned it as “thinktime” because it was allowing students to sort out their thoughts.