"What's my pin?" Living with Long Covid

As variants emerge and anti-vaxxers push, I talk to a friend who survived Covid - but is forever changed

Note: This essay on Long Covid also exists as a podcast, which you can find here.

Webworm exists thanks to paying subscribers. If you like what you read here and want to support this newsletter, you can sign up here. Only do this if it doesn’t cause you any kind of financial hardship. Subscribers help keep important stuff like this free for everyone.

Hi,

I find driving on Los Angeles freeways quite stressful as cars aggressively weave in and out of traffic like they’re in a Fast & Furious film. There is no chill.

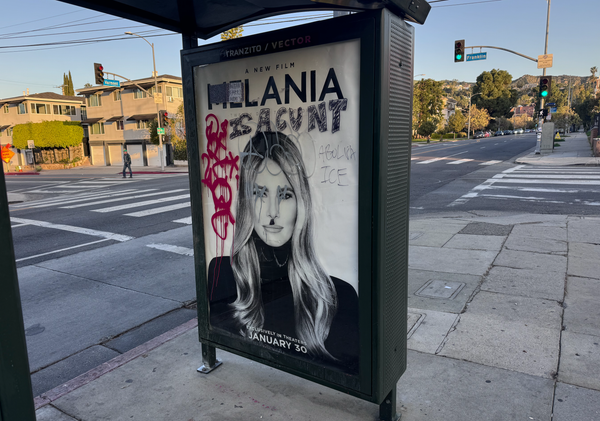

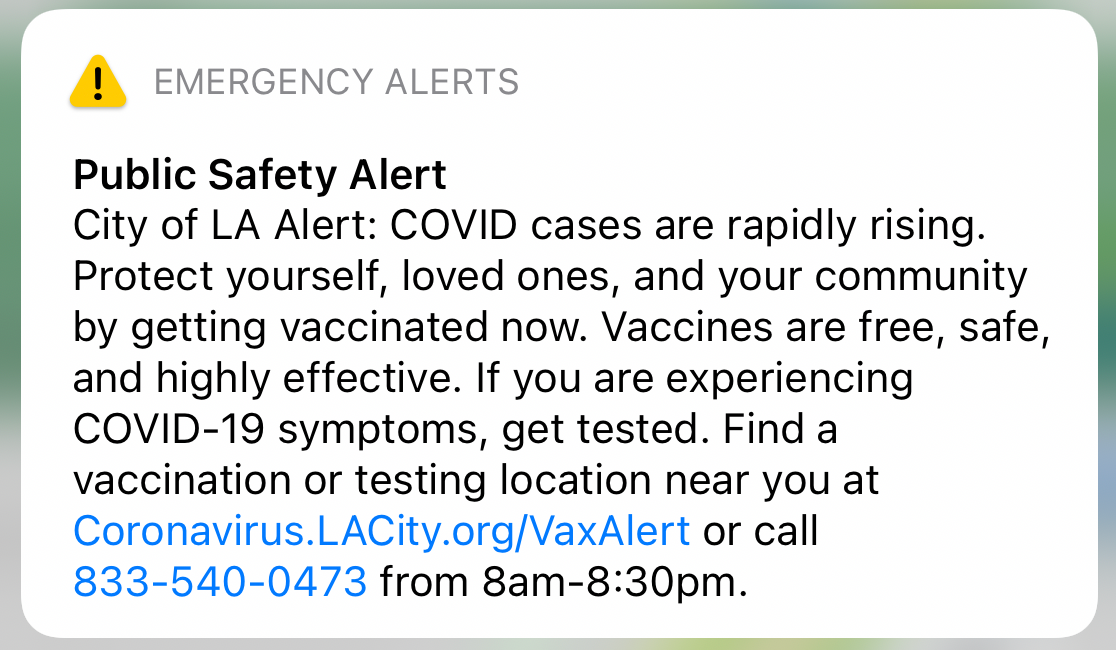

What usually helps with this stress is my little maps app keeping me company on my dashboard — telling me where to go. But not today, oh no, because suddenly this “Emergency Alert” took over my phone, making my precious guidance system disappear.

It was a reminder that we’re living in a world that is forever different. We aren’t going back to normal just yet. The pandemic is still doing its thing, and we have to be vigilant — getting vaccinated and wearing masks in crowded places.

And yet — we’re hearing from human toenails like Ted Cruz telling us that Covid ain’t no big deal.

No more giving up our freedom to over-controlling government bureaucrats who want to shut down our schools, shut down our businesses, and shut down our lives!

— Ted Cruz (@tedcruz) 12:22 PM ∙ Aug 2, 2021

I find this sort of rhetoric annoying and incredibly selfish — because while many of us will never get Covid, some of us will.

And then there’s that line we’ve all heard — and maybe on some level, believe: “It’s just like the flu”.

But here’s the thing: that’s simply not true for everyone. And I think it’s really important we remember that, as we get frustrated at travel restrictions in some countries, or mask-wearing policies in others.

And so today I wanted to deliver you a really brilliant essay from an old colleague of mine, Jez Brown.

We both used to work in the TV3 newsroom in New Zealand. I was a reporter, he was a really great editor. At one point, we both found ourselves sitting next to each other at a Marilyn Manson concert (this was before we knew he was a piece of shit).

Eventually Jez outgrew New Zealand, and moved to London. And that’s where he caught Covid. Long Covid.

I wanted to learn about his experience, and so Jez agreed to write an essay for Webworm. I think his piece is insightful, heartbreaking, terrifying and at times — quite funny. Really funny. I know that seems weird, but it is.

David.

Living with Long Covid.

by Jez Brown

I’ve forgotten my pin number.

I mean, really forgotten it. The brain sent a request down to long term filing and got a 404.

This wasn’t merely a case of bumbling fingers or a reverse numerical keypad: When the bank showed me my pin, I didn’t recognise it at all.

This is ‘Long Covid’.

My pin, the same pin I’ve had since I moved to the United Kingdom from New Zealand five years ago, was gone.

A pin I’ve used hundreds of times and on this day wanted to use — to top up my travel card to get into work and then to buy lunch while I was there — was awol, and left my eyes groping between my card and the keypad, the brain and fingers bereft of a response to queries like “please enter your pin number”.

My pin, no small triviality, suddenly and randomly extracted from my memory.

I’m Jez, I work in broadcasting, and I like to use my bank card to get around and buy food.

I flit the line between creative (the money hole) and technical proficiency (generating money to throw in aforementioned hole).

I’m the sort of guy who owns seven ukuleles he can’t play, but can set up a mind-blowing audio visual system to play them through. You don’t know they’re the wrong notes if your head has melted!

I can also normally recall a four digit sequence of numbers designed to expedite access to financial services.

Born in 1980, I grew up in New Zealand’s most boring town (it won several awards), before starting in radio and ending up in TV.

At the end of 2016, dissatisfied with a lack of creative opportunities in the Butt Shaky Isles, I decided to roll the dice elsewhere.

“Britain!” I thought. “They make great comedy television! They’d certainly never leave the EU or allow a deadly virus to spread uninhibited, I’ll go there!”

I’ve lived a fanciful life in Britain since, freelancing for major broadcasters and wallowing in the consumption of bountiful creative arts which aren’t so forthcoming when you’re geographically isolated at the arse end of the world.

And while I never managed to worm my way into comedy television as I’d hoped, I’ve kept myself afloat working with some great people making interesting things, not starving to death, or freezing to death, or catching a nasty vir —

I caught Covid in April 2020.

I had been back in the UK for all of a month. My Grandmother had received the grim diagnosis of Leukemia at Christmas, and I had bolted back to New Zealand to be with her. It was a nice summer.

While we laughed and filled our bellies with Kiwi treaties, the occasional mention of some virus in China would lazily and unremarkably scatter itself amongst the news: Nothing to worry about, only good times to be had — until you run out of money and remember you make yours on the other side of the planet.

Grandma and I shared some last jokes, she hobbled into the kitchen where my worried mother asked “what do you want to do, Mum?”.

“Die!” she jeered, without missing a beat.

Oh, how we laughed! Well, how Grandma and I laughed. That special bond, acknowledged, but perhaps not celebrated by the other family members.

Then came the painful goodbyes and it was time to return to Blighty. This was the end of February. My Grandmother would pass away in March. I would not be there for the funeral, but I’ll be forever grateful my family could be. New Zealand would go into lockdown the following week.

I would work through the end of February back in Britain, there were no limitations or curtailments on my journey there, and no restrictions on the island either — but I was now working on stories about a virus which was China’s problem.

But then, it was our problem.

New Zealand locked down. Britain did nothing.

I made protestations with one of my employers about the risk we were now facing and in an act of ghoulish British subservience was told they were sticking to government advice.

More countries locked down. Britain did nothing.

A friend and I put differences aside and prepped for lockdown. Recognising it was better the devil you know than no-one at all, I moved in with her and we became part of the hoards scrambling for toilet paper and tins. She could now work from home, but I was deemed essential, had nothing in the bank, and had to go in to work.

No facemasks, no hand gel, no screens or dividers, no social distancing.

No plan.

As offices closed around the world, ours was flooded with people flowing in over Britain’s wide open borders. People got sick. I got sick.

I got very sick.

You know when you get sick and you think “tis but a cold” or you think “better write up a will”?

I wrote up a will.

It started with a fever that woke me in the night. A cough soon followed, raspy, scratchy and persistent. My energy waned, my hands turned blue, I collapsed.

No ambulances were available, they called me a taxi. I spent a day in hospital, sitting upright in a children’s plastic chair, watching patient after patient arrive, assessed and taken away. Around 10pm they sent me home because they had no beds. I’m paraphrasing, but it was pretty much “Call us if you die”.

For two weeks I wrestled with the virus, people remarking on television that it was “just like the flu”. As my hair turned grey — my mind muddled and the death toll spiralling — I wondered what kind of flu they were referring to exactly? Perhaps when they get the flu, their dicks fall off or their spines explode, and this by comparison was sort of a doddle.

The next two months were spent largely sitting quietly in a chair binge watching Tiger King and Attack on Titan, unable to gather the strength to do more than slowly and soothingly build a Lego Voltron. We recorded an unlistenable daily podcast, but at least it gave our days some structure and made us talk to each other.

I would grunt, shamble and grumble, a befuddled zombie roomba. When I tried to speak I would stutter, stumble and falter.

My vocabulary fell away, if I used real words at all. I was forever distracted and incapable of remembering where sentences had started, as I became increasingly frustrated at not being able to find the words to finish what I didn’t know I was talking about.

Then, finally, I started to get better, I started to become more active. But then I didn’t. I didn’t get better.

August arrived.

I’d turned 40 without fanfare. I’d fallen out with my friend after the foolhardy folly of lockdown frolics. I was back in my own flat, “Lockdown 1” was over and the government pushed a meme friendly scheme called “eat out to help out”, the precursor to “Lockdown 2: 2 Slow 2 Lockdown”.

My mental health was on toast. Unable to return to New Zealand, I kept pushing out a date I might be able to go home. A year later, I still am.

I’d been trying for weeks to get an appointment with my GP to discuss the issues I was having. “Long Covid” now entered the public’s collective consciousness.

I couldn’t climb a flight of stairs, I couldn’t walk around the block let alone run. Sex was suddenly a chore or near death experience, I had rashes all over my hands and I had put on weight.

My sense of humour, so much a core element of my personality, ghosted me. I felt who I was as a person had been fundamentally attacked.

I was bitter, compromised and difficult. I met a nice girl and I blew it.

Lockdown returned and so did work.

The thing about “the brain scramblies” — otherwise known as “brain fog” — is that it can wax and wane. You have good moments and bad, the ebb and flow of what you’re capable of in the moment as opposed to all the time.

To begin with, conversations were difficult — but with practice, I improved.

Conversation was still stilted, but manageable — and I needed money! I went back to work, but with a new challenge: remembering what the buttons do, what the icons mean, and fighting the internal struggle to string two thoughts together — all while keeping my shortcomings secret from my colleagues and employers.

As a freelancer, you don’t get fired, the phone just stops ringing. I was deeply afraid this would be the case if people knew what I was going through, and how difficult I was finding even simple tasks.

I couldn’t see friends for lockdowns, and many had left the country. I couldn’t go home and I didn’t have a support network. All I had was work and the piece of mind that at least I wasn’t having to worry about money. I was in a dark place and knew losing work would be the camel that broke the bridge too far.

So I fought on, re-teaching myself to do the job I’d done the previous 15 years. Muscle memory more than real memories, I couldn’t remember old girlfriends’ faces or my shoe size, let alone which key did what on this shmancy-pants keyboard. I fought through the fatigue, I fought through the scramblies, I fought through every frailty I had.

Until — I popped.

As I’ve since learned from being referred to the “Long Covid Clinic”, they think the brain problems are “a software issue, not a hardware issue”.

In other words, not brain damage so much as brain befuddle-fication. And the reason it ebbs-and-flows comes down to what you’re making the brain do.

At this point, to me, ‘nouns’ were something that happened to other people and the most basic recollections were award winning.

The doctors I’ve seen think the brain is constantly operating at full capacity: executive function trying as hard as it can to do the things the brain would normally find easy. This state of constantly being switched on is very draining, and like any computer pushed to its limits it can suddenly shut down.

This is what happened to me — twice — while making live television for two different broadcasters. I’m not sure what you know about live television, but it’s a high pressure environment dotted throughout with a raft of ‘intense personalities’.

I called these moments where my brain would shut down ‘silent migraines’. The sudden onset of tunnel vision, an inability to string two thoughts together and an increased sensitivity to any light. In both these instances, I just had to stop what I was doing, try to explain, and lie on the floor.

If you didn’t already know, it’s very hard to explain something you don’t understand to people who don’t want to hear it with words you don’t have.

These attacks occurred under stress and before December, when I was finally embraced by the massively overstretched healthcare system. A GP’s appointment I’d waited eight months to get, for a referral in another three months time. Time for “Lockdown 3: Exactly What You Did Last Summer.”

By this point I had just been given my first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine, which my body reacted to kicking and screaming for a couple of days like I had Covid all over again.

But then I improved. A lot.

Let’s be clear, I’m not better, but after I got over the symptoms of that first jab, it was like a veil had been lifted.

My fatigue went from chronic to occasional. My vocabulary exploded. Words came out of my mouth I hadn’t heard in months and had forgotten I knew. I would stop talking not because I couldn’t find the words, but because I wondered if I just shit myself with surprise.

My wit returned, I could remember some people’s names, I could hold a sentence together from beginning to end and I could damn well — well, no: turns out it didn’t cure lactose intolerance.

I could go into my first Long Covid appointment with positive news — and they could give me some I didn’t expect.

The virus had damaged my heart.

For a relatively fit, non-smoking, barely drinking 40-year-old such as myself, to hear that my heart was damaged was — news.

After everything, could I now die of a broken heart?

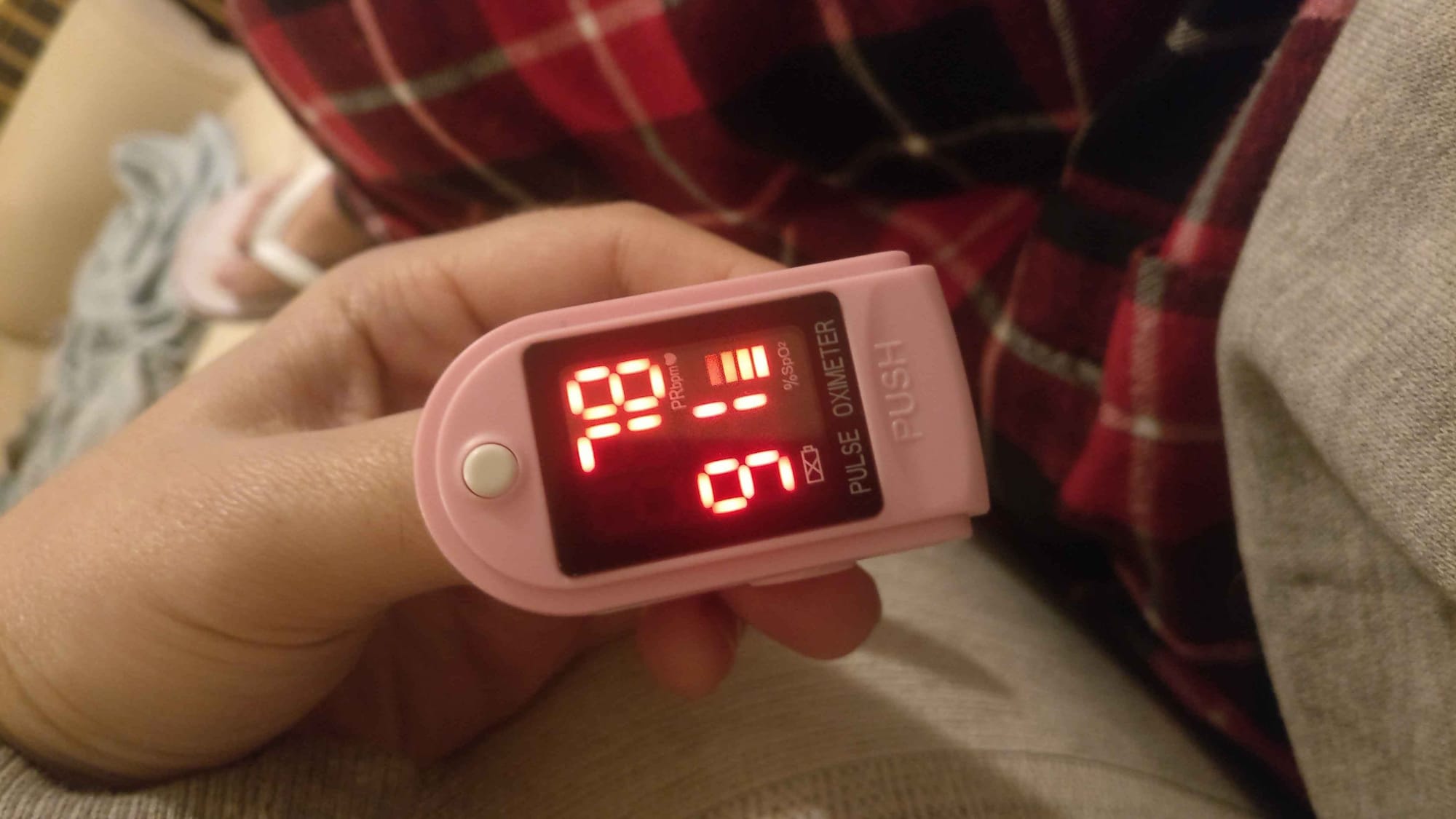

Blood tests, scans, MRIs, CTs — I’m in hospital a couple of times a week at the moment.

I’ve been prescribed pills, but can’t see my GP to get them. Just today I got a txt from my GP asking me to make an appointment to discuss the letters they’ve been getting from the hospital, but when I rang, like always, there are no appointments available.

My lungs have been stress-tested too: They look ok on the x-rays — no fibrosis to speak of a year after Covid — but under duress they don’t get me enough oxygen and no-one knows why.

Cognitive tests would be my chance to shine. I was asked to recite addresses just given to me, remember animal names, and draw a clock face.

I could do none of these things.

How the bloody fuck have I been able to keep doing my job over the last year? How have I managed to maintain output and keep up appearances despite myself?

When you look at the crudely drawn incorrect clock face in front of you, all you can think is “No I’m doesn’t”.

And I’d be right.

I try to maintain a modicum of laissez-faire, but I’m also moody and belligerent. I’m now deeply forgetful, time is no longer relative to what I can remember, and I’ve become withdrawn in my attempts to cope. I take things a day at a time, but how long’s a day and how many days has it been?

My memory is full of holes and the memories I do have are fractured and disassociated.

Where I was once a walking jukebox, attempts to sing along with songs these days are embarrassingly incorrect.

This letter, written mostly in a single day, took a further week to re-write because each paragraph felt like it was written by a different person: Any flow or feel lost to the temperamental machinations of my haphazard inner monologue. Even now it feels bitsy and chaotic. It got cleaned up a lot today because I had a good day after a series of bad ones, but who knows what tomorrow will hold.

And that’s the big difference: easy things are now a lot harder.

Staying in touch with friends — so important to me — is now a lot harder now. I hope in reading this, they might come to understand why I’ve been vague or aloof — meaning to get back to them, and never doing so.

Sent messages that were left unfinished, or felt like they had no context. Why I might share a joke or meme with someone they don’t get at all, because it’s the punchline to a set up I sent to someone else — who is still waiting for that punchline.

I’m exhausted and incoherent, but I’m trying to do my best.

As I lay under my desk at work this morning wishing I was anywhere else, I was reminded of just how little it currently takes to tip me over the edge. The farcical nature of Britain’s response plugged directly into my negative feedback loop as I try to make sense of my life and the world around me.

We’re now in the pingdemic, the result of millions of people having to self-isolate as the virus runs rampant in Britain.

You get pinged by the National Health Service app when you contract or come into contact with someone who has the virus and must stay home and isolate. So widespread have the pings been, that people are now deleting the app to avoid it. The upshot? Cases appear to go down while hospital admissions continue to go up.

This is why you don’t race blindfolded horses… but Britain reckons it’s an appropriate response to a deadly pandemic. The British government would tell you all racehorses are put out to stud and certainly not turned into dog food.

Sex in paradise forever and don’t look behind the glue factory. “Long Covid” means you’re one of the lucky ones.

As we careen towards “Lockdown 4: Live Free and Die Hard”, I’d love to go back to New Zealand, to see my friends and family, to recharge.

But I can’t.

It’s a very weird feeling not being able to return to your home country, not because you don’t want to or can’t afford it, but because you can’t. That’s not really an emotion or thought I think you can get your head around, until you’ve experienced it. It’s a very difficult thing.

New Zealand’s borders are closed and I’m glad. I’m glad my friends and family are safe. They’re even safe from me and my big squeezy hugs. But how long will they be safe from Covid? I posted a picture of me with my heart monitor on facebook today, reminding people to get their jabs — and someone unfriended me. I guess the nips were too much.

If you’re reading this, get your jabs. It’s not the flu and anyone who says so is so, so punchable. Punch them from me. Say I said you could.

The toll on me from being stuck overseas has been huge, but I’ll take it if it means my loved ones are safe. That doesn’t mean I don’t want to come home to New Zealand — it’s grandiose vistas, its socially irresponsible broken housing model, its lamentable extortionate food prices and its wonderful wonderful people. Hi Wayne.

I want to come home, even if it’s just for a while. Britain has once again neglected science in favour of politics, choosing to open up while the virus reaches ever greater numbers of people.

More deaths will follow, another lockdown will follow, and if Satan’s got a say — another variant will follow soon too. That’s a shame because Satan is into some really good music, but this is southern states Satan and he’s a bit “Fuck y’all”.

That’s the approach of Bojo’s Britain: masks be damned, social distancing is for wussies and hand-gel is only for fisting. We’ve got a long way to go.

I need a take away, what’s my pin number?

-Monday August 2nd, 2021.

You can follow Jez for updates on Twitter here: @jez_brown

This is his website: jezbrown.co.uk

David here again. Usually with guest essays, I don’t edit them very much — I want people to be able to speak their mind.

This case was no different — apart from a few minor formatting things, these are Jez’s unedited thoughts.

But I want to make it clear that this wasn’t an easy thing for him to write. As well as being deeply personal and revealing, he also just had to cope with the new way his brain works.

He talks about this a little in his piece — “each paragraph felt like it was written by a different person” — and I wanted to commend him for sticking with it. I know writing this wasn’t easy for him: each time he’d sit down to tackle it felt like starting for the first time. This was technically a very hard thing for him to write.

So thanks Jez.

And as for wearing masks, Ted Cruz? Yes — wear them if you’re in crowded indoor spaces in a country riddled with Covid. The vaccination is a great preventative measure for catching Covid — but it’s not fullproof. That was never promised. I mean, even if you wear a seatbelt there’s still a chance you will die in a car crash. But you wear the seatbelt. So get the vaccine, but don’t throw away the mask just yet. Be safe.

David.

PS: You might recognise this guy from the opening montage in Tickled:

Mr Lordi, singer of Finnish heavy metal band Lordi, receives his second dose of Covid-19 vaccine in Rovaniemi, Finland on August 1, 2021.

— Michael Deibert (@michaelcdeibert) 1:09 PM ∙ Aug 2, 2021