The Possum: Demon or Friend?

I had an encounter that changed everything.

Hi,

I felt a small wet tongue snaking through one of the holes in my Crocs. It explored my big toe, darting down one side, then the other. “He’s looking for some toe cheese,” said the woman next to me, words that still haunt me to this day.

Growing up in New Zealand, certain things are drilled into you with reckless abandon. This includes a massive resentment towards anyone who “gets too big for their boots”, a deep love of New Zealand’s native (and sometimes flightless) birds, and a deep hatred for our most loathed animal: The possum.

The creature was first brought to New Zealand in 1837 by our mortal enemy Australia in order to establish a fur trade. They quickly bred out of control, tearing through the country’s native bush and birdlife to become our most despised pest. Farmers hate them for carrying bovine tuberculosis, and schools have special days dedicated to arming their students up the eyeballs so they can murder as many possums as possible.

Hating possums has become a favourite New Zealand pastime, and any article attempting to redeem them is met with a mixture of ridicule and disgust.

But there is one thing New Zealand’s possum has going for it: They are, in the opinion of this author, horrifically cute:

So imagine my surprise when I got to America and saw their version of the possum, which appeared to have escaped from the lower pits of hell.

I was greeted by a creature with bulging red eyes, a disgusting rat-like tail, and a hissing mouth filled with razor sharp teeth. 50 razor sharp teeth, if we’re being specific. I was, in a word, shook — especially when I combined this sight with what I knew about possums: they carried disease, ate all the cute bird eggs, and reduced lush forest to wooden graveyards.

But we all get things wrong.

“He’s looking for some toe cheese,” said Brenda, an American who has a deep affection for the possum.

During the day, Brenda works as a veterinary technician — but in the hours outside of that job she’s helping rescue and rehabilitate Los Angeles’ possum population.

“They’re North America’s only marsupial. I do love that. They also seem to be the underdogs, so I like that. You know, there’s dog rescuers and cat rescuers. There are raccoon rescuers. Nobody ever thinks about the possums. So I figured, you know, they need help. They need an advocate and I figured I would be that person.”

She is that person. She’s been that person since she was 17, off to college and stumbling on a possum that needed rescuing. Decades later, she’s just gotten deeper. Her life is possums — and right now one of her rehabs, Horace, is tonguing my big toe.

I first ran into Brenda on Instagram, where she posts regular updates about Horace and the other possums she’s rescued. It was there that I first started seeing another side to a creature I’d assumed the worst of.

“People think they’re vermin. They think they’re dirty, diseased, big rat creatures running around, which is not true,” Brenda tells me. She has Horace on a little lead, like a cat. We’ve met up in a local park, and as we talk you can see people walking past clocking us. Me with my pink hair, Brenda with her red hair, and this giant American possum licking my toes (these possums are bigger than New Zealand’s).

“That’s what most people think. They usually don’t know that they're actually really good for our environment. They’re our clean up services.”

She’s not wrong — they eat a load of ticks, as well as the trash and scraps humans leave lying around. In America, it appears they’re eating everything but native bird eggs and rare foliage. “Their diet is actually extremely varied. There was a scientific report done where they checked deceased possums to see what they were eating. And their diet ranged from, like, nuts and berries to, like, bugs to hamburgers and fries.”

Everything I was learning about the American possum was shifting my perception.

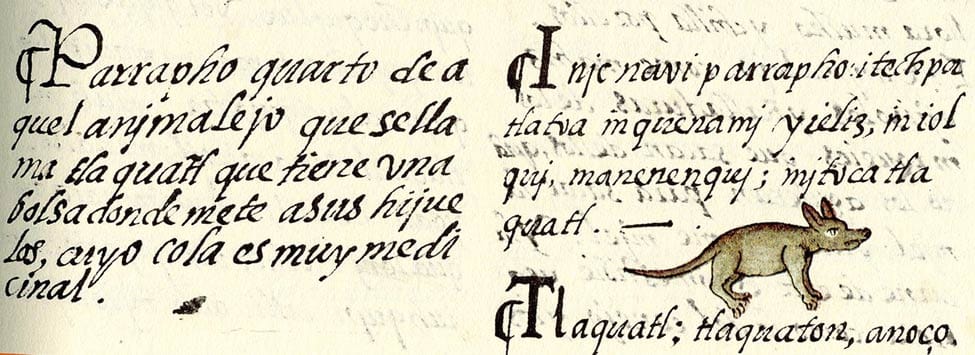

Like many people, I’d assumed the possum was related to the rat. Turns out they have a pouch, just like a kangaroo — which makes them a marsupial. North America’s only one.

They’re also what experts call a living fossil.

70 million years ago, when dinosaurs were walking the earth — possums not too dissimilar to Horace were there as well. Unlike most creatures from that time that died out, possums didn’t. This whole time I’d thought of them as some kind of evolutionary mistake, but maybe I had it wrong: from a survival perspective, they’re sort of perfect. 70 million years and still going strong.

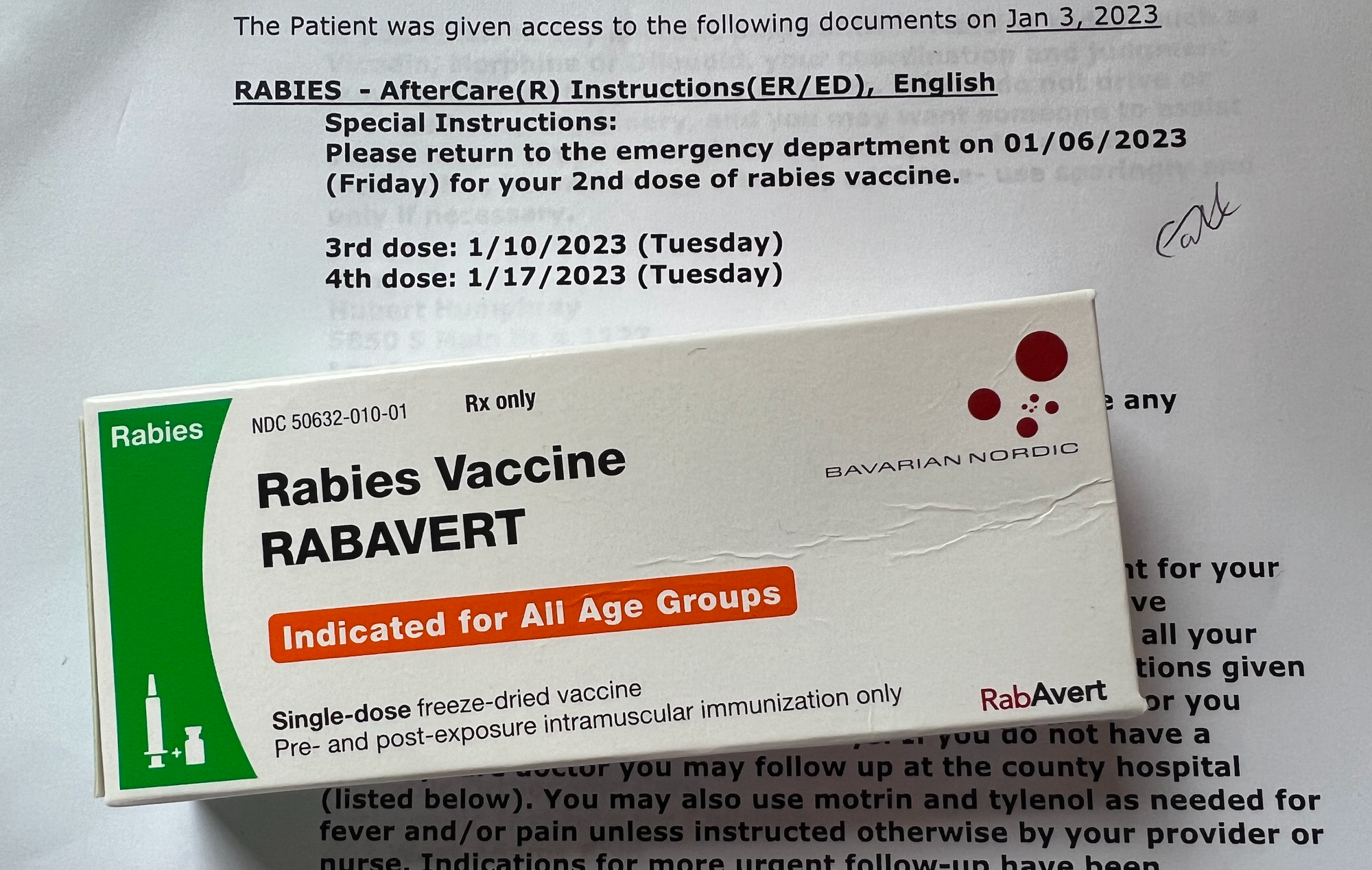

I was also delighted to find out that they’re pretty much immune to rabies. “Opossum physiology tends to be very different from most mammals, and it’s mammals that carry rabies. Their temperature tends to be very low, so they don’t reproduce the rabies virus, which is good for us,” Brenda tells me.

As someone who has endured an array of expensive rabies shots in my butt, this made me incredibly happy.

As I watched Horace, I started to realise he was… kinda cute.

He moves slowly and carefully, his eyes wide and soft like a creature from a Pixar film. If anything, the only crime Horace could be accused of is of being pathetic. His main line of defence is literally playing possum — a process entirely out of his control, much like those fainting goats I watch on YouTube when I’m feeling depressed.

A scared possum will simply fall down, a built in defence mechanism making their lips draw back to reveal those 50 teeth, saliva pouring out to make them appear rabid. It’s all just an extended pathetic trick, probably best portrayed in this video of a woman presenting a wild possum to her friend.

All of this is going through my mind as I do something no New Zealander has ever done*: I picked up a possum with care and love.

(*they have, I just wanted to be dramatic),

Looking into Horace’s eyes, my heart melted.

His tiny paws gripping onto me in a nervous embrace.

As a New Zealander and (North American) possum forged an unlikely bond, a guy wandered by, laughing. He was grinning ear to ear, pointing at this creature on a leash that most Americans considered a pest. “Zarigüeya!” he yelled, a word that I didn’t understand.

Brenda filled me in.

“The Spanish word for opossum is zarigüeya, and that’s a Mesoamerican term. So before the Spaniards came to Mexico and conquered everything, it was an era of when the Mayans and the Aztecs ruled the empire. And in some areas of Mexico, possums are actually considered like a blessing to have,” she tells me.

“There is an old story that says way back in the day, people and animals lived in darkness. And one day, a comet fell down to the earth, and this wicked old hag found the comet and stole all the fire from the comet for herself. And then the possum and all the animals were like, “Can we have some fire at night to keep warm, and so we can see each other?” and the old hag was like, “No”.

“So the possum thought to himself, “I’m going to hook you guys up. So he went into her den and befriended the old hag, and then when she fell asleep, the possum actually grabbed a piece of fire with his tail and ran it back to his friends and the people. So the reason why the possum’s tail is naked is because it got burned off when he was delivering fire to his people.”

I look down at my feet, where Horace is now fast asleep. While the New Zealand possum’s tail is soft and fluffy, his is entirely naked and devoid of fur.

The legend makes sense.

Brenda laughs. “Although, some tales also say that his tail is naked because he was super vain and the gods took away his fur. But I like the first story.”

I spoke to Brenda awhile back, not quite sure what I was going to do with our conversation.

It’ll probably turn into a Flightless Bird episode at some point, but over the last few weeks in New Zealand I was reminded of Aotearoa’s hatred for our possum, and America’s assumption about its possum.

I’d assumed the possum I’d found in North America was a more dastardly version of New Zealand’s — but nothing could be further from the truth.

And so I sat down and wrote this Webworm, curious to see where you sit on creatures that society has pushed to the outer edges.

Before I left Brenda, I asked what her advice was for Americans interacting with this misunderstood oopsie.

“Well, I guess the right answer for coexisting is that mainly we should just leave them be — if they’re passing by to their next foraging spot, or if they're just trying to get home to their nesting area.”

She reconsiders.

“But… if you want to be a fun yard, and there’s not a lot of dogs in your area, you can provide some shelter in the winter or some food, or some water during the summer. Then that would be lovely. Your house isn’t going to be where the possum hangs out. They will walk up to three miles a night searching for things, but it would be a welcome relief area to cross upon some water when you know it’s a dry area.

“So technically leave them be, give them their space. But if you want to be friendly… possums love free things, you know?”

PS: I left out explaining how possums carry their babies around on their backs. The photos are amazing, but I showed a friend and it terrified them. Something to do with too many eyeballs. Trypophobia maybe?