Advice For Coping With 2026

Webworm gets a trauma & bereavement counselor to weigh in.

Hi,

Can I begin assuring you that today's Webworm is positive and hopeful. And useful. But it has to start with a short rant for context.

Last week I felt like I wanted to extract part of my brain with a fork.

Back in 2022, I spent a good part of the year exposing bullying, abuse, and the coverup of rape at New Zealand's biggest megachurch, Arise.

That series led to the leaders John and Gillian Cameron (along with John's buffoonish brother Brent) resigning and fleeing overseas. And while I'd already reported that John and Brent were attempting to restart their grift in Australia, nothing quite prepared me for punch to the guts I felt when I saw the launch video for their new church:

I thought about the hundreds of victims who were thrown aside, and how it's all just going to happen again. And I watched as their new church's Instagram page (and John's and Gillian's) blocked negative feedback – shutting down their victims yet again.

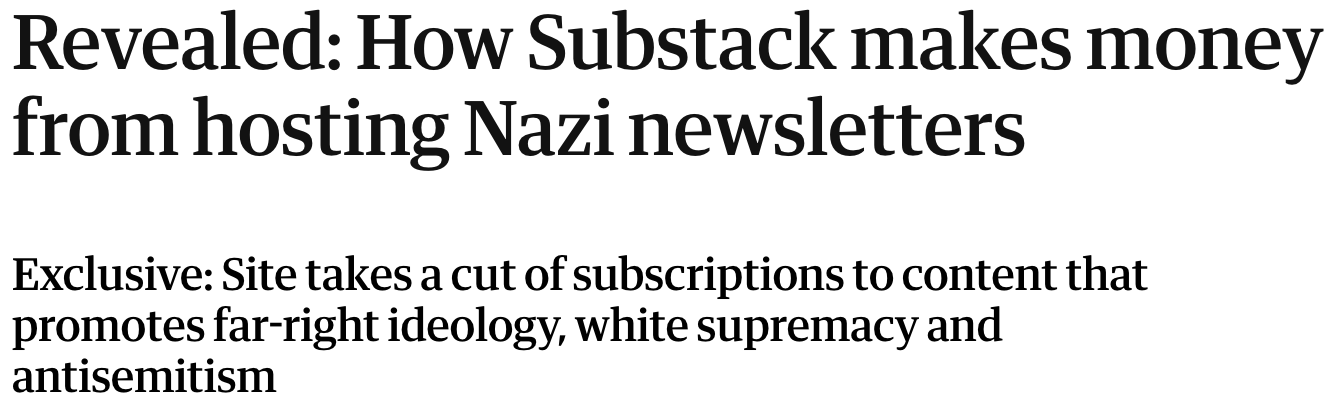

With that burbling over in my mind, I then read more billionaires' names in the Epstein files, caught up on the latest crimes being committed by ICE and the US government, saw the bets taking place on Polymarket, tried to wrap my tiny brain around Iran, and learnt that Homeland Security is definitely tracking online criticism of the administration. Oh, and then Trump posted that blatantly racist image of the Obamas as apes.

It felt like I was getting pummeled by multiple waves, all at once.

What is my point? Well, I figure you may too be finding the world quite overwhelming at the moment. Stuck in this weird ether between trying to make sense of what the hell is going on (and trying to help), and feeding your cat and getting the laundry done.

So today I wanted to bring you some really smart, practical thoughts on how to cope. That advice comes from Ross Palethorpe, a trauma and bereavement counselor. I needed to hear these words, and I figured maybe you do, too.

David.

The Laundry Always Needs Doing: Grief and Resistance

by Ross Palethorpe

I’m not a fan of laundry, housework, and “life admin” (as we were nauseatingly calling it online about ten years ago). Our family is at the stage where we’re past the nappies and unidentified slimy objects on clothes, but with two adults, one kid and two big dogs, my forties are a constant battle against endless dog hair, gym clothes, odd socks and paw prints on the sofas. Like most people, my partner and I both work full time in jobs that don’t finish when we leave our offices, and the hours after we get home are spent on trying to make sure we’re ready for tomorrow while trying to process and let go of today.

We all live lives in many places at once. We’re unblocking the sink while ruminating on that awkward interaction at the supermarket while listening to a podcast about the latest appalling news Out There. We’re watching Netflix while trying not to think about that meeting on Friday (who emails with “We need to talk” and no context in 2026!?) while scrolling our feeds where pictures of preschool kids being abducted and death squads gunning down moms on the school run are interspersed with a new foster dog meeting their family and an artist capturing the sunrise while in the distant recesses of our subconscious, a siren is wailing.

Grief, as I conceptualise it, is the process of letting go of the life we once lived and the acceptance that from here, nothing will be the same. When someone dies, we grieve the life we had that contained the person who died, in all their messy, complex glory. The mourners are all grieving the same person, but each grieving the loss of that person in their own life in a way that is deeply, heartbreakingly individual.

We can grieve the loss of an opportunity, a relationship, a redundancy in ways that can be as profound and life-altering as losing a loved one. We all grieve, in a million different ways, all the time, even if we don’t recognise it for what it is. It’s an experience that is both universal and unique, connecting and isolating.

In grief therapy, we talk about what is dryly titled the “Dual Process Model”. In my own practice, I think of grief as a place. A world of its own. Time moves differently here. In grief, the colours are wrong. Like some distant planet, our bodies move and interact with their environment in an unfamiliar way. The air can feel suffocatingly thick, or so thin that no inhale ever seems enough. It can feel hostile, overwhelming, a place where any life is precarious and the greenery, if it exists at all, feels alien.

Back in the real world, the laundry always needs doing. The dogs are politely reminding us that dinner was due three minutes ago. That report needs doing by next week. The real world is familiar, in its endless petty demands and bills due and what do you mean you didn’t empty your lunchbox on Friday. Who wants to spend any time in a strange, dangerous Other Place when netball practice starts in twenty minutes?

However, grief is not a place that is as far from our everyday world as we’d like to pretend. It exists in tandem, its borders invisible and overlapping. Like Besźel and UI Quoma in China Mieville’s The City and The City, we may feel like inhabitants of one place forbidden to acknowledge the existence of the other, but feel the influence of the space we are reluctant to step into regardless.

Modern European culture is obsessed with patrolling borders, and grief is no exception. We whisper to each other that the widow is “bearing up well” at the funeral, a shorthand for “not making us feel uncomfortable”. We’re offered a few days’ leave from work when someone dies, and we turn ourselves and each other away from those more liminal losses, with exhortations to always look forward, to have no regrets.

But no matter how high the walls or how sharp the razor wire, the grief is always there, with a gravitational pull that refuses to let go.

This cultural approach to mourning can pathologise those who seem trapped on the other side of the wall.

The DSM-V has given us the concept of “Prolonged Grief Disorder”, which gives clinicians a handy checklist for when grief has pushed past acceptable societal norms. It suggests that an adult who is experiencing dissociation, avoidance, intense emotional pain, meaninglessness etc. a whole year after the loss of a loved one may be diagnosed with PGD. For children and adolescents, it’s six months. Half a year before your grief is diagnosable.

The Dual Process Model of grief asserts that, in order for us to grieve, we must become dual citizens. We must consciously spend time in that alien world, feel the loss, explore its landscapes and let our bodies adapt to the terrain. We encourage rituals and intent, to remember the dead and their place in our lives, but to then walk back through the gate and into the everyday world.

Spending time in each place may not make grief any less painful, but helps it feel less unfamiliar, less terrifying. Stepping back into the everyday means that we are reminded of the life that continues without what has been lost, and our place in it.

Many people who have been bereaved talk about the strangeness of stepping out of the hospital or funeral home and seeing people going about their lives as though nothing has happened. By keeping the gate open to the world of grief, we can acknowledge that our lives can and will continue, but we don’t have to pretend that nothing has changed.

I reflect on this in early 2026, when so many of us are grieving.

Grieving the loss of a future we had hoped would exist but that is being trampled on by billionaires, fossil fuel companies, death squads on suburban streets. Grieving people we know, and those we don’t, who have been killed in landslides, at the side of the road, in overstretched hospitals from preventable diseases.

The sense of loss is compounded by seeing those close enough to the levers of power that they could stop this, any of it, choosing to instead ask for yet more donations and saying that someone else should do something, but only in the right way, a way that will hopefully not upset anyone. We’re told over and over again that we must carry on as normal, that everything is fine, that the sirens are a false alarm or a false flag and that all we need to do is ignore it, someone will find the off switch soon, get back to work.

When grief becomes forbidden and transgressive as much as it is all-pervasive and overwhelming, it makes sense that so many of us become trapped in the zone between. That sense of paralysis, of the old Soviet concept of hypernormalisation. What is the point of doing the goddamn dishes when the house is burning down.

We hear a cacophony of voices from either side, telling us to either step over into grief, or ignore it altogether. Don’t look away/move along, GoFundMe for rent/the economy shows signs of recovery, they're bombing us again/your luxury 2026 summer holiday picks!

This is where intentionality and acknowledgement can help us out of the paralysis. An acceptance of the situation as it is, and also that it is not what we want it to be.

Attending to grief in a time of resistance is action and ritual as much as any private mourning. The grief world is following unmarked cars around St Paul, reading about the Epstein files, attending a vigil, phone banking for progressive candidates, crying at the state of it all. For many of us, our current situation is so far outside our everyday existence that it feels shocking, disorienting, but in order to function the grief must be attended to.

And then, equally important, we must step back into the world where the laundry is waiting. Feeding ourselves, finding comfort in that TV show we’ve watched a hundred times, taking the dog for a walk or listening to our kid explain Minecraft for the thousandth time. The everyday is what we spend time in the grief world for. It is connection and nourishment and rest and dumb memes and online arguments over where you store the butter.

We attend to grief so that we have an everyday world that not just persists, but thrives, and becomes a world that is more just and fair.

So if you’re reading this and, like me, have found yourself in that liminal zone between grief and laundry, take a step in either direction. Attend to the grief in a way that is meaningful to you, and then step out into the mundane and attend to the life that makes the grief work necessary.

Accept that, for the foreseeable future, we are dual citizens in a culture that finds the very idea transgressive, and find ways to let go of the idea that we can only exist in one place.

-Ross Palethorpe works as a trauma and bereavement counselor. He lives in Otago with his family and two rescue dogs.

David here again. After sitting with those words, the urge to remove part of my brain with a fork has decreased. For now. We'll see how the week goes.

Maybe you have your own thoughts and advice, or feedback. Feel free to share it below. You know the drill.

Other Stray Sunday Thoughts:

1. Rethinking Joseph Gordon-Levitt

I've had a few people asking recently if I've had a change of heart towards Joseph Gordon-Levitt, who has apparently "been doing very good things lately."

Context. Five years ago I wrote a series on the Inception, Dark Knight Rises and Snowden actor called "Has Joseph Gordon-Levitt Lost His Mind", in which I expressed my cynicism about JGL's social media project. I was slightly surprised when JGL read it and reached out – which led to a part II in the series.

It all concluded in part III, where JGL called me while I was attempting to cook dinner to explain things even further.

That was back in 2021. Have I changed my mind? Not really.

For some reason, JGL's been on Capitol Hill advocating for the dismantling of Section 230. On it's surface, this move by various conservative figures promises to make for a safer internet, with better moderation. But as Mike Masnick explains over on TechDirt, the dismantling of Section 230 is a very, very dumb (and bad) idea.

(Masnick is the guy I interviewed while deciding to leaving Substack behind.)

So in short, no: I have not changed my mind about Joseph Gordon-Levitt. I think he has his heart in the right place, but like a big eager puppy trying to be a good boy, he just ends up knocking all the vases over in the process.

2. A Quick Note About Substack

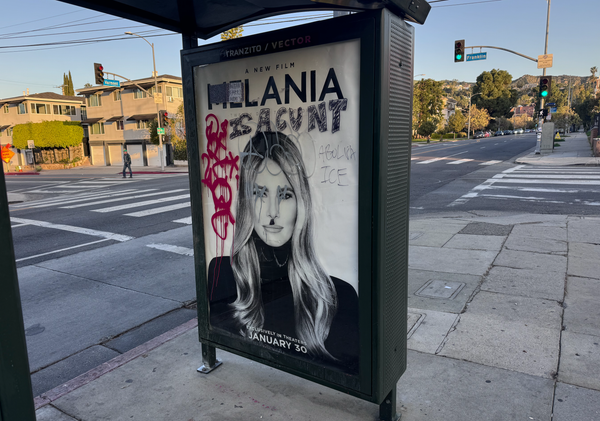

I think it's worth noting The Guardian did a big piece on Substack and its "Nazi problem" over the weekend.

(Substack is, of course, where Joseph Gordon-Levitt recently set up his own newsletter. Not because he's a Nazi, just because he's a big eager puppy trying to be a good boy.)

The Guardian piece is great, but is unusual in that is made out like all this was new information:

"Revealed! Exclusive!" But of course all this had already been detailed at length by The Atlantic back in 2023. I detailed my reasons for leaving last year – the Nazi stuff was a big part of it, but there were other reasons, too.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from The Guardian's story is that nothing has changed over at Substack HQ. And that's a huge bummer.

Okay. Time to prepare to watch Bad Bunny play the halftime show. I'm going to try and keep Ross' words in mind this week:

"For the foreseeable future, we are dual citizens in a culture that finds the very idea transgressive, and find ways to let go of the idea that we can only exist in one place."

David.

More from Ross Palethorpe: