“We're not freezing you. We vitrify you, OK?”

I have been spending time with the CEO of Alcor, and he wants to vitrify you.

A very boring bit of admin first. If you're reading this and you were on a discounted rate on Substack (due to being a student, or on a benefit, or just in a rough patch) - that discounted rate followed you here. Now in your profile, it's going to show you that you're on the "full member" tier (and price) - but please know, you're still getting that full membership on whatever discounted rate you've always been on. The fact your discounted price is not being displayed to you is just an annoying limitation with the migration process. If you have any questions on this, please email me anytime: davidfarrier@protonmail.com - and remember to check out the FAQ about Webworm's migration from Substack to Ghost.

Hi,

If you want to freeze your cat or dog in the hope that future generations will figure out how to bring Frido back to life one day, it will set you back between $29,600 and $143,400 US dollars. That’s for the whole pet. If you want to freeze just the head, it’s closer to $7000.

Humans are a little more expensive. A whole body costs close to a quarter of a million dollars. Just the head? That’s a tidy $80,000.

These prices all come from Alcor, the world’s first, and still biggest, cryonics institute. It sounds like a combination of bad sci-fi and scam - but now labs in Russia and Australia are opening their doors to offer similar services to humans who are not ready to let go.

It all sounds patently ridiculous - but Alcor has over 250 bodies (and heads) cryogenically frozen in a building in Scottsdale, Arizona. And 1500 other Americans are signed up, deposits on the table, waiting to join them.

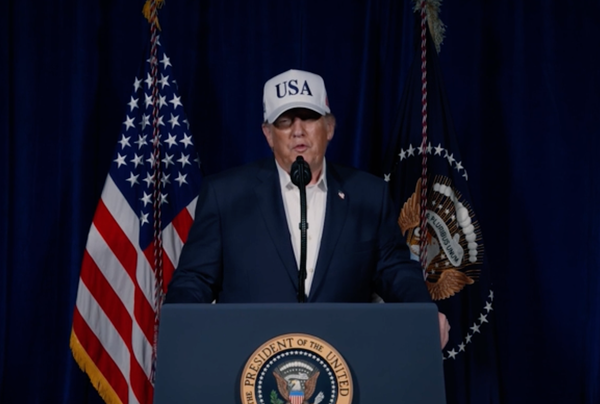

This year I’ve been spending some time with the CEO of Alcor, James Arrowood, to try and figure out what the hell is going on.

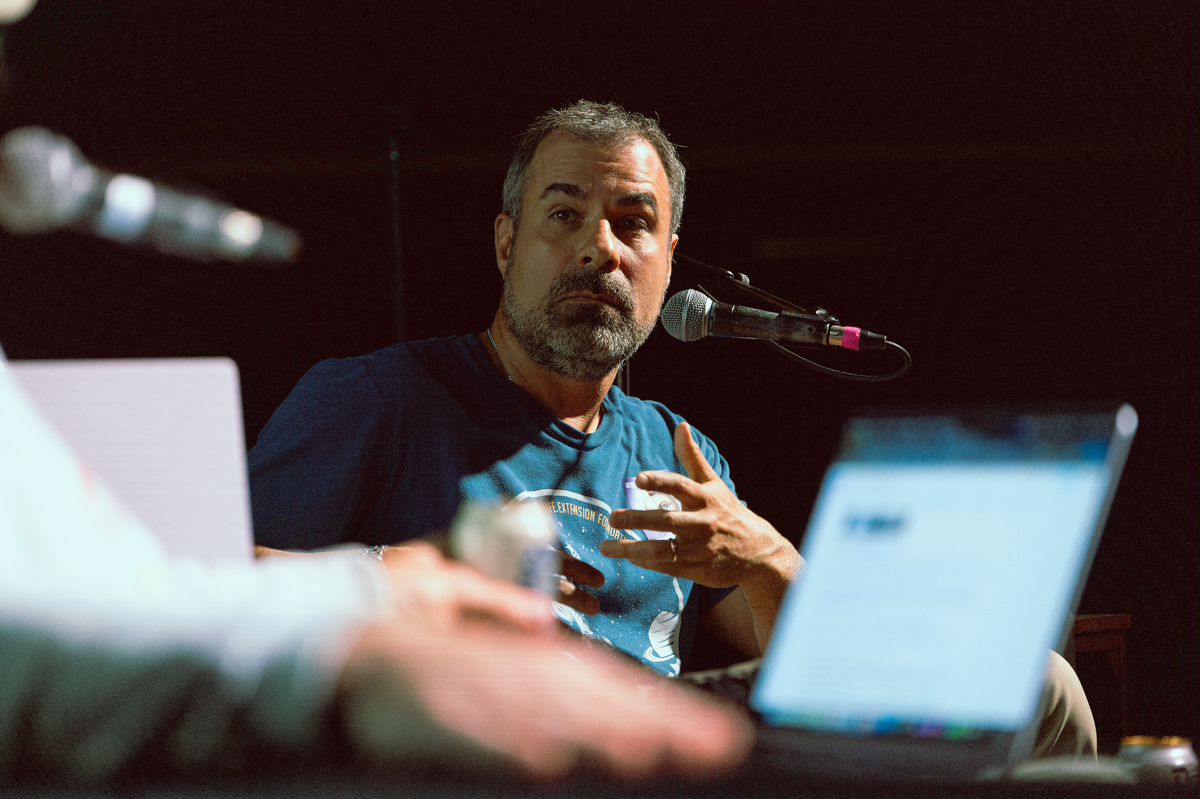

“Rotting in the ground, that's never appealed to me,” he tells me. Arrowood is tall and wide, a tight blue Alcor t-shirt making his frame seem even bigger. He wears a light silver chain around his neck, and he talks incredibly fast - weaving from point to point with multiple tangents along the way. I’ve got used to his style of speaking, but I still always leave feeling exhausted.

“I mean you're literally worm food and stuff, and some people are cool with that, great. Not me. I mean, think about how every moment of your life has been in support of your brain, so why just roll it and toss it because some arbitrary accident takes you out?” he asks.

I’m not sure I have an answer.

"I Cannot Confirm Or Deny"

Alcor, and the whole idea of “cryonics” (not to be confused with cryogenics, a legitimate branch of physics that studies matter at freezing temperatures) is deeply, deeply American. Former Boston Red Sox player Ted Williams underwent “cryopreservation” back in 2002.

Centuries earlier in 1773, Benjamin Franklin wrote, "I wish it were possible from this instance to invent a method of embalming drowned persons, in such a manner that they may be recalled to life, however distant."

American author Neil R Jones is credited with coming up with the idea of freezing someone to achieve a kind of immortality in his 1931 book The Jameson Satellite.

And in 1964, Robert Ettinger posited cryonics as a real, feasible thing in his book The Prospect of Immortality writing, "No matter what kills us, whether old age or disease, and even if freezing techniques are still crude when we die, sooner or later our friends of the future should be equal to the task of reviving and curing us."

Three years after that book came out, the first American was frozen - Professor James H. Bedford, a 73-year-old retired professor and cryonics fanatic.

And in 1972, Alcor began - freezing its first patient in 1976. It’s the company that would go on to freeze that Red Sox player Ted Williams. Allegedly.

Arrowood bristles a little when I raise Williams. I would find out why later. “He's been publicly identified as being with Alcor, but I'm not allowed to confirm or deny, because [clients] choose to be confidential. I have to do a lot of ‘cannot confirm or deny’,” he tells me.

Before James joined Alcor, he worked as a lawyer. “At a mega firm, a huge firm, and all over the country” he says.

“I get a phone call and they say, ‘There's this company and we don't know what to do with them. It’s just too weird for us.’ And I had never heard of cryonics per se. But when you think about it, it makes sense. It merges a form of kind of healthcare, or what we like to think of as ‘continuation emergency medicine’, with this state of the art mechanical engineering, chemical engineering, those sorts of things. So while it was very, very strange to begin with, it made a lot of sense for my skill sets and background.”

He tells me - in many of his vague digressions - that he's also run various medical facilities, so was perfect for the Alcor job. After eight years of giving legal advice to Alcor, he transitioned into the CEO role.

He’s now trying to get Alcor into the public eye, which is why he agreed to talk to me, first appearing as a live guest on my podcast, and continuing to talk to me ever since. And the whole time, I just kept thinking: This is the man whose company has 250 bodies and severed human heads on ice.

Ice Is The Bad Guy

It’s not as simple as throwing a body in the freezer. While most people call cryonics a pseudo-science, those in the field are certainly trying to do science.

Death To Dust: What Happens To Dead Bodies?, a book published in 2001, goes into some the details around the cryonics process, writing:

Once the cryonics technicians get control of a corpse, they reinstitute cardiopulmonary resuscitation and, as quickly as possible, put the body on a heart-lung machine similar to that used in an operating room.

Cryonicists say that under optimal circumstances a body can be on the machine within thirty minutes after death. Once the body is attached to this machine, technicians rapidly cool the blood [...] then administer drugs that supposedly reduce damage from decreased oxygen going to the tissues.

Cryonicists watch the brain during this process through a hole made in the skull. They then submerge the body in a bath of silicone oil for 36 to 48 hours, cooling it to a temperature approximating that of dry ice.

When the body reaches this temperature, it is wrapped in a pre-cooled sleeping bag, placed inside a protective aluminum pod, and lowered into an insulated container (dewar) to which liquid nitrogen is repeatedly added in small amounts.

After it has cooled, the body is transferred to another, larger, dewar that is filled with liquid nitrogen.

Each custom-made "Bigfoot" dewar weighs almost 2 1⁄2 tons, stands nine-feet high, and can store up to four bodies. A dewar boils off 12 to 15 liters of nitrogen per day.

When I ask James what Alcor’s process is for freezing their recently dead clients, he immediately shuts me down. “We're not freezing you. The whole point is not to freeze you. You don't want to be frozen. What we do is vitrify you, okay?”

He goes on.

"Vitrifying in the simplest terms means we're trying to cool your cells down to an ultra-cool temperature without ice forming. Ice is the bad guy here. Everybody can think of ice as being sharp, and on the molecular level it's like a bunch of razor blades essentially. So that's obviously really bad around cells.

The other problem with ice is that everybody knows if you put the plastic water bottle in the freezer. So you get crushing injuries on the molecular level of cells.

So what we're trying to do is we're trying to remove water - but your body is seventy percent water.

So we take out your blood, which is putting the water in your body, and we replace it with a different fluid that's almost a gel-like substance, it's thicker. It prevents ice from forming, and then we perfuse your body with a higher concentration of this gel solution, which is extraordinarily expensive, and then we try to essentially flash freeze you."

My eyes narrow, and he catches that he just said “freezing” himself. “But in a very controlled way,” he adds. “And there's sensors and computers.”

Ever the hype man, James hands me a t-shirt after one of our meetings. It's official Alcor merch, with an illustration of on astronaut in space. Earlier he'd told me he's been meeting with "important people" in tech, although he can't tell me their names. "There's space companies in Europe, so I have to travel out to Europe soon. And I guess China now, which is crazy? So there's just a lot going on," he tells me.

They've been talking about the use of cryonics for deep space travel. Afterall, how are humans meant to survive the 300 year-long journey into space without putting themselves into a state of suspended animation first?

Back in 2004, Canadian biochemist Kenneth B. Storey called the idea of ever bringing a frozen corpse back to life “impossible”. He said to do so, scientists would have to, "Overturn the laws of physics, chemistry, and molecular science".

When I put this quote to James Arrowood, he shifts in his seat and laughs. “That's hilarious. It's hilarious you mention that. I think you should reach back out to him and see if he still feels that way,” he says.

"I've actually met with the legitimate, top physicists on Earth. Inarguable credentials on these people. Top universities. And one of the things that killed me about two years ago, [an Alcor member] said, ‘You know, James, I would not acknowledge you if you came to any of these scientific conferences. I would pretend not to know you, and I would be critical of cryonics’, and I'm like, ‘You're signed up!’

So what’s ironic is that some of these scientists you’re mentioning in these fields - particularly cryobiology or thermodynamic engineering - they can look around a room, and there's gonna probably be a at least 5-10% of people in that room that are signed up [to Alcor] and are pretending not to be. I'm making a wide statement there, and I understand that, but understand I'm privy to this. And it blows my mind."

I ask for names, but like with Ted Williams the baseball player - it’s all confidential. Corpse-cryonicist privilege, I suppose.

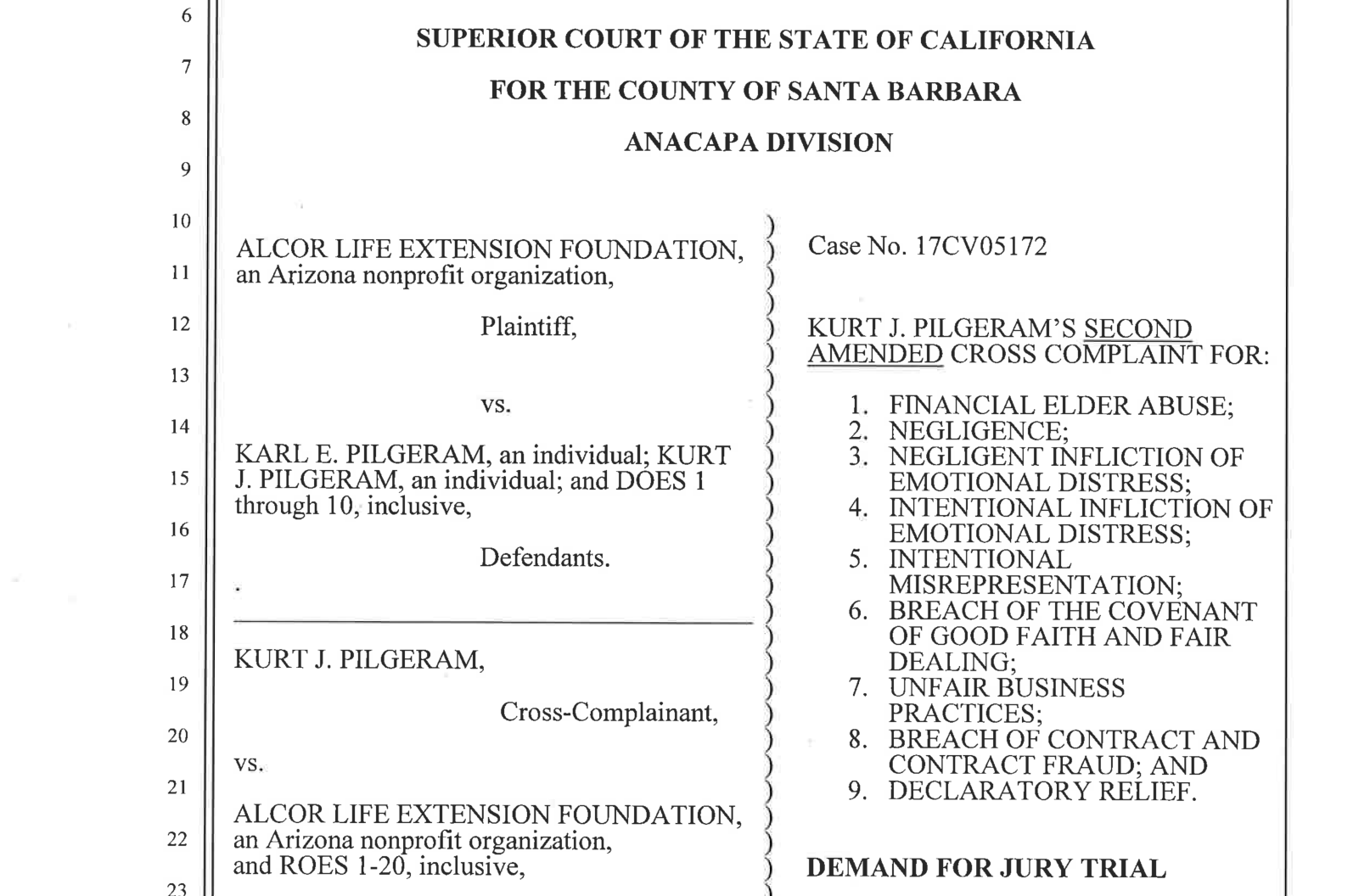

But whenever I start to wonder if all of this is a joke, I remember that there are real bodies on ice, and that some are deadly serious about all of this. Back in 2018, Alcor was sued by Kurt Pilgeram, who said Alcor only froze his father's head instead of the entire body. How would his father come back to life without his body?

I have no doubt Alcor needs a good lawyer at times; and I guess they have one in their CEO.

Genuine Belief

Arrowood tells me that around 10% of Alcor’s members genuinely believe that future science will crack the puzzle of how to thaw them out, and bring them back to life.

This 10% is on the more extreme end of belief, fueled by sci-fi that sees Sylvester Stallone emerging from ice to fight Wesley Snipes, or Ripley (and her cat) reclining in the Nostromo's deep space cryo-chamber.

To them, being frozen is the equivalent of faith in God and an afterlife. When they die, they do so convinced they’ll be back, and better than ever. When pressed on this, Arrowood is firm that Alcor are not selling the guarantee their clients will be brought back. “I'm not selling anything, and I'm definitely not promising something that you have to have faith to believe will happen, because it's just not me. And I am not going to be in charge of an organization that's doing that,” he says.

He tells me 80% of clients are simply banking on odds, figuring that they stand a better chance by being frozen, as opposed to rotting in the ground or turned into dust via cremation.

And the other 10% assume they themselves absolutely won’t be revived, but will perhaps add to the science that will allow future humans to become immortal.

The idea of being revived from an icy slumber hundreds of years in the future is daunting. Assuming your brain cells are not 95% mush and you don’t have to be immediately taken out the back and put down with a bullet, you’re living in a world ravaged by AI and climate change. Your friends, lovers and family members are all long dead.

If you couldn't afford full-body preservation, there’s also the issue that you’re just a head. Although that extreme 10% of adherents would argue that a future civilisation that’s figured out how to bring you back would also have developed a synthetic body to pop your brain in. Arrowood indicates he's excited about those prospects.

I guess we’ll have to wait to find out. Just don’t make me the first one out of the tank. Sorry, let me get my language right: Out of the dewar.

We've Got Heads

“At the time, there was actually a bunch of litigation surrounding that, okay? So you have to be careful about that,” Arrowood tells me.

I’ve raised the 2009 book Frozen: A True Story - My Journey Into The World of Cryonics, Deception and Death. I’d ordered before my latest conversation with Alcor’s CEO, surprised to find just one lone copy available on Amazon.

“I'm gonna look into that, because I'm surprised you're telling me you can still buy it,” he says. “I wasn't there, and I wasn’t involved with Alcor at the same time this all went down.”

What “went down” were allegations of animal experiments, the dumping of dangerous chemicals, and the particularly unhinged way heads were removed from some corpses before being frozen. The book alleged that, “Alcor’s hired surgeon smashed through the patient’s spine with a hammer and chisel to remove the head. It looked like the surgeon was hacking at a tree stump.”

Author and former Alcor worker Larry Johnson also alleged one recovered body had been driven through the desert in the back of an unrefrigerated U-Haul truck, arriving in “repulsive” condition.

“I don't think he worked there long. There is a judgment against him. So take that as you will,” says Arrowood.

Frozen also alleges former Red Sox player Ted Williams’ frozen body was poorly treated at Alcor, stored in a malfunctioning machine so that it could be easily recovered if the courts got involved.

It’s not an entirely far fetched premise. Williams had died in 2002 from congestive heart failure. His will stated that he wanted to be cremated, but his son and daughter rallied to have his remains cryogenically frozen. Ted's other daughter sued, saying her father never wanted to have his head frozen.

Frozen is an incredibly compelling book, only suffering from the same issues as Alcor’s CEO - a tendency to exaggerate and add a sense of drama to nearly everything.

Perhaps drama is deep in Alcor’s bones. Alcor sued Larry Johnson in 2010, sending out multiple press releases about the case including “Larry Johnson Found in Contempt of Court; Warrant Issued for His Arrest” and “Larry Johnson Held in Contempt of Court and Forced to Post Bail in Nevada to Avoid Jail; Lawsuit Continues in New York”.

Although it was successful in getting the book’s website shut down, Alcor’s 2010 Defamation Complaint against both the publisher and author was dismissed in 2014.

Arrowood tells me Larry Johnson and co-author Scott Baldyga were simply writing the book in order to shop around a Hollywood script. It’s not out of the question; Frozen is written like a Dan Brown thriller, and Baldyga has a list of minor credits on IMDb.

“There's so many urban legends about Alcor, in particular because of what we do, and I get it. I mean, we’ve got heads!”

Whatever you think about Alcor, it's not the only organization toying with cryonics. This year, Southern Cryonics opened its doors in New South Wales, Australia. Their website announces they are, “The first cryonics storage facility in the southern hemisphere, serving an area across all states and territories of Australia, as well as New Zealand”.

They aim to, “Provide a professional ‘one-stop’ service that makes cryonic suspension affordable and readily available in Australia” and to, “Promote scientific research into cryonic suspension, revival, and life extension.”

Professor Bruce Thompson from Melbourne’s School of Health Science has raised ethical concerns about the outfit, calling it “Star Trek in play”.

When it comes to cryonics, ethical concerns are never far away. As well as obvious questions around selling false hope and how clients will be reanimated, there are more basic issues. Should money and resources be put into such an expensive, energy-sucking enterprise? Does pressure fall on relatives to keep paying the bills to keep a loved one frozen? Will the need to be frozen as close as possible to the time of death lead to a temptation for an assisted death?

None of those questions have stopped Southern Cryonics. According to the ABC, they currently have two bodies on ice, with 32 active "subscribers".

And back in 2005, Russia’s KrioRus opened its doors, the first non-American company to delve into cryonics. Despite being Russian, it stores bodies and heads from the Netherlands, Japan, Israel, Italy, Switzerland and Australia.

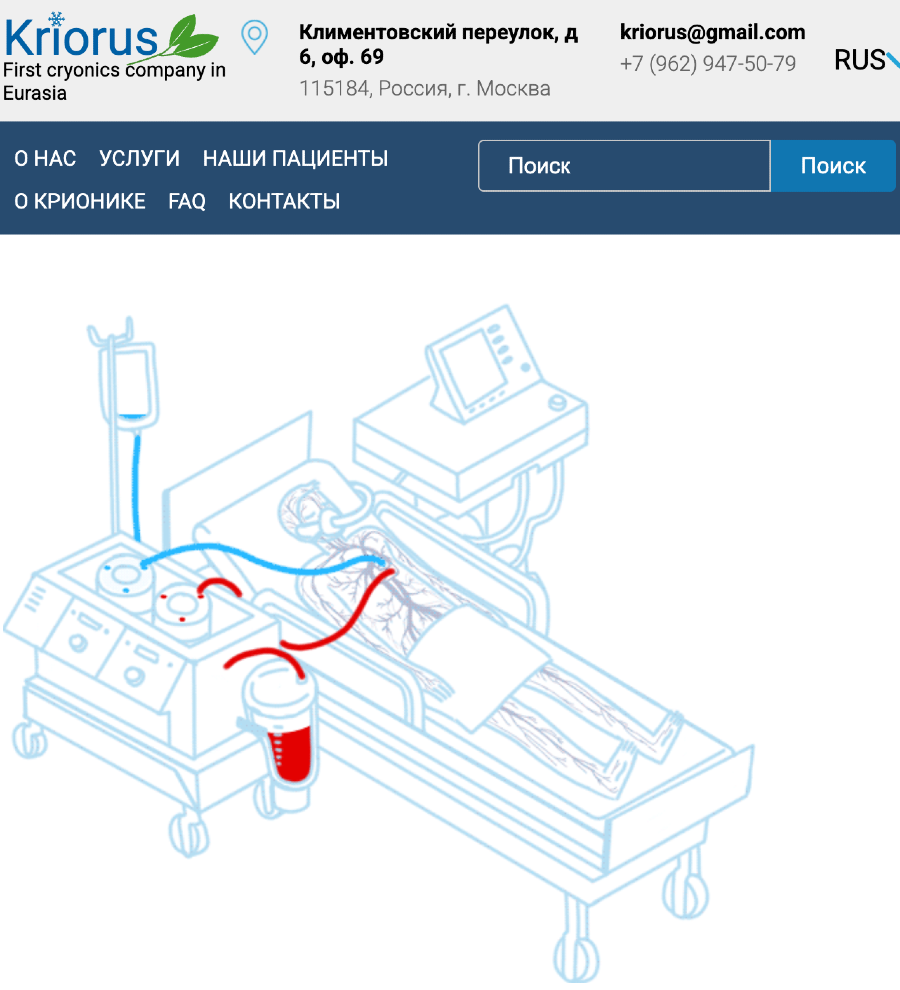

An illustration on their website demonstrates the general methods agreed upon by cryonicists: removing the blood before applying healthy doses of liquid nitrogen.

Clearly, the idea of living forever has appeal outside of the United States. A lot of people are putting serious effort into making immortality a reality.

Perfectly Normal

Just when carefully curated illustrations have me starting to believe there is some kind of science here, I get thrown. As I was working on this story, I met up with John Wilson who created HBO’s How To With John Wilson. He kindly curated a tiny Webworm event for New York readers, and afterwards we went to a bar and started talking cryonics.

We spoke about a particularly surreal and shocking scene in Wilson’s TV show in which a cryonics enthusiast (someone Arrowood would class in that upper 10% of clients), casually tells Wilson that he performed self-castration in order to get rid of unwanted sexual feelings.

His arched back and overall demeanour stuck with me, and I realised I’d seen him before - in a Bloomberg photo-essay about Alcor.

There he was, castrated and standing in front of a two-tonne dewar cooled to -320 degrees Fahrenheit. The man is R. Michael Perry, first hired at Alcor in 1989. He currently works there as “Care Services Manager”.

Perry is tasked with maintaining Alcor's stock of human remains. He'll have the job of checking on Arrowood's severed head, provided his boss dies first. James tells me he's a "neuro", meaning he'll only be vitrified from the neck up. He has faith that future scientists will be able to grow human bodies by then, so his brain can be unfrozen and placed in a younger, better, stronger body.

“Well, because my body's so beat up, and if I make it to 80 or something, I'm basically a cyborg at that point anyway.”

He says it so casually you could be forgiven for thinking this is all perfectly normal. Which to anyone in the world of cryo, it is.