Those Metal Motherfuckers: Cinema in the Year of AI

"AI isn't being met with resistance because we're already accustomed to it - our shit is no different to its shit."

Hi,

I wanted to share this piece by film editor Dan Kircher about what cinema has been up to in 2024.

Dan edited my documentary Mister Organ, as well as this year’s excellent crowd-pleasing Bookworm.

Dan adores movies. He gets the language of cinema, he knows what he loves, and writes accordingly. And this year — he’s had AI on the mind.

David.

Those Metal Motherfuckers: Cinema in the Year of AI

by Dan Kircher

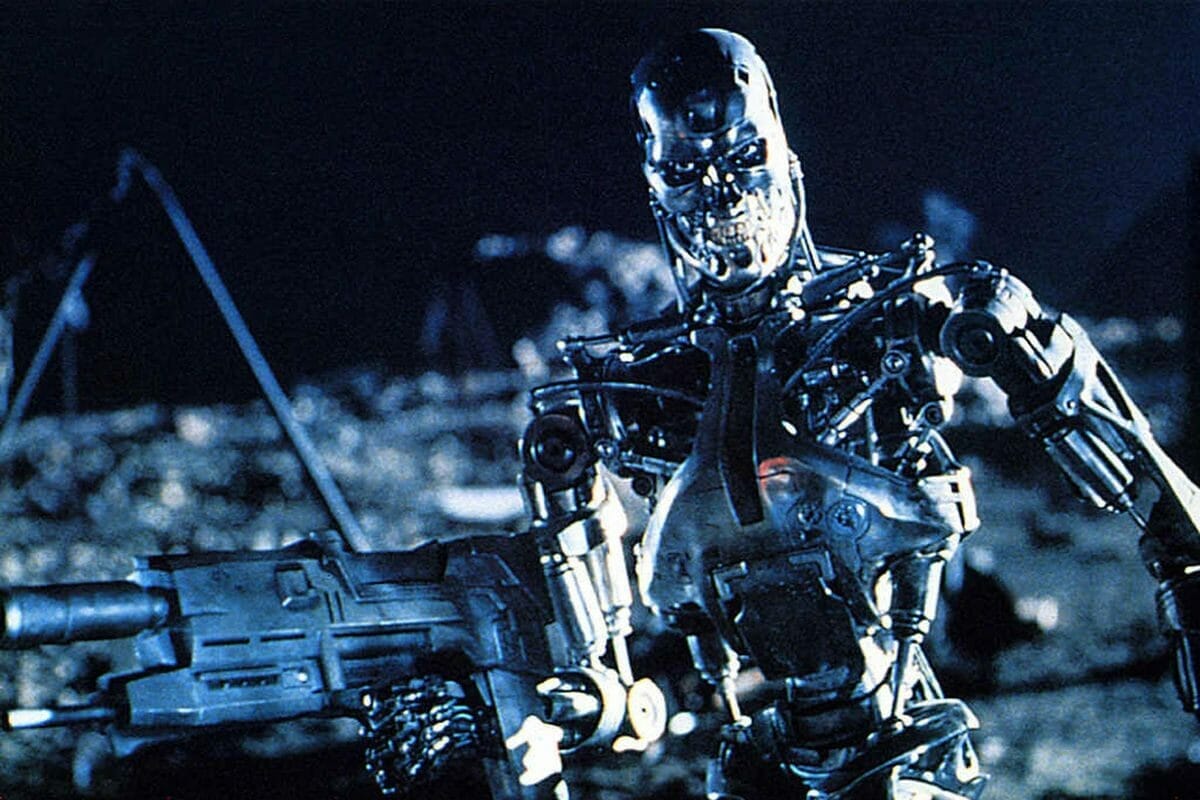

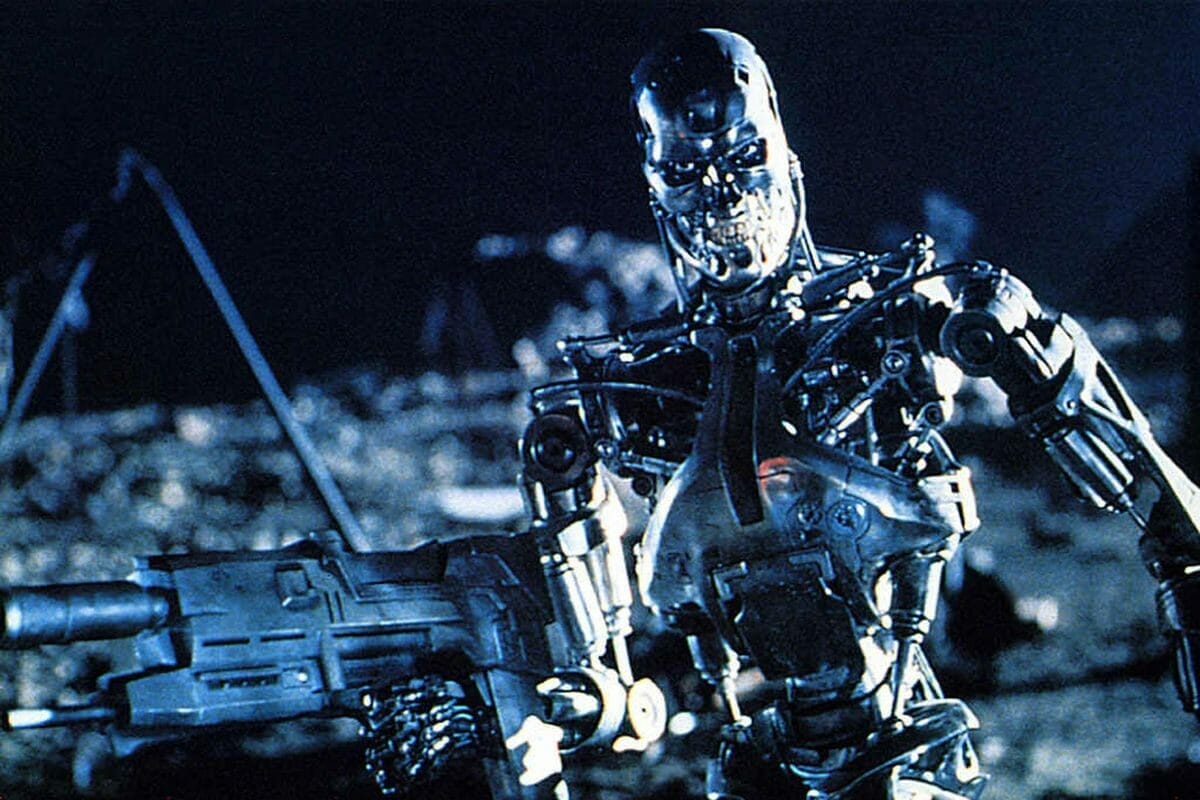

In 2024 we were treated to several high profile restorations from megalomaniac auteur James Cameron's back catalog. Cameron's aggressive defence of the laughably grotesque reissues - which were aided and abetted by the ubiquitous image-obliterating processes commonly referred to simply as "AI" - had me wondering whether the Terminator director himself hadn't been personally remastered. Is Cameron now just living tissue over a metal endoskeleton? How else could you explain the director of so many scrappy, muscular and very human blockbusters proceeding to systematically machine-tool them into uncanny valley sludge?

“When people start reviewing your grain structure, they need to move out of mom’s basement and meet somebody," Cameron said. "I’m serious. I mean, are you fucking kidding me?” After a quick scan of original/restoration frame comparisons from True Lies, I'd argue it's not just Cameron's grain structure we should be reviewing. Alongside fellow tinkering technophiles George Lucas and Robert Zemeckis, he’s lost the ability to discern between, much less align, form and function. But like his indelible cyborg, Cameron can't be reasoned with, can't be bargained with. His position is unwavering: "All the Avatar films are done that way. Everything is done that way. Get a life, people, seriously."

Life is what's missing from these remasters, and from movies in general. After a certain tipping point of pixel fucking, everything feels like a facsimile, regardless of how it was achieved on the day. It sticks out when you're looking at revised versions of products from the practical, celluloid age, but this quality also now imbues new releases with an inherent unreality, a feeling that even if the movie allegedly was made with real actors performing in real places with a real script, it kinda doesn't matter because the result is indistinguishable from something an AI generator could pump out with a few prompts from a junior studio exec.

This must be registering with the gatekeepers, at least a little. As the Wicked press tour steamrolled the trades for several weeks in November, there were an inordinate number of pieces about how much of the film was "real". They say they planted nine million tulips, which end up on screen as if someone copy-pasted the same digital tulip asset nine million times. Director Jon Chu took it upon himself, more than once, to defend the movie's colour grading, after audiences continued to notice how crappy it was. "I think what we wanted to do was immerse people into Oz, to make it a real place,” Chu said about the completely fake looking film.

Overbearing twitchy posturing like this is the default mode of communication for cinema's saviour Tom Cruise, who channels his infinite energy primarily into justifying the price of admission to his own projects. These too invariably lean on how real everything is, but in the end his films look as augmented as anything else. The most recent Mission: Impossible featured Cruise as humanity and the movies' last hope, his puffy digi-face valiantly battling an evil AI through the requisite set pieces, all of which were less tangible than the famously computer-generated Chunnel finale of Brian De Palma's first instalment, now nearly three decades old and still better than any of the others.

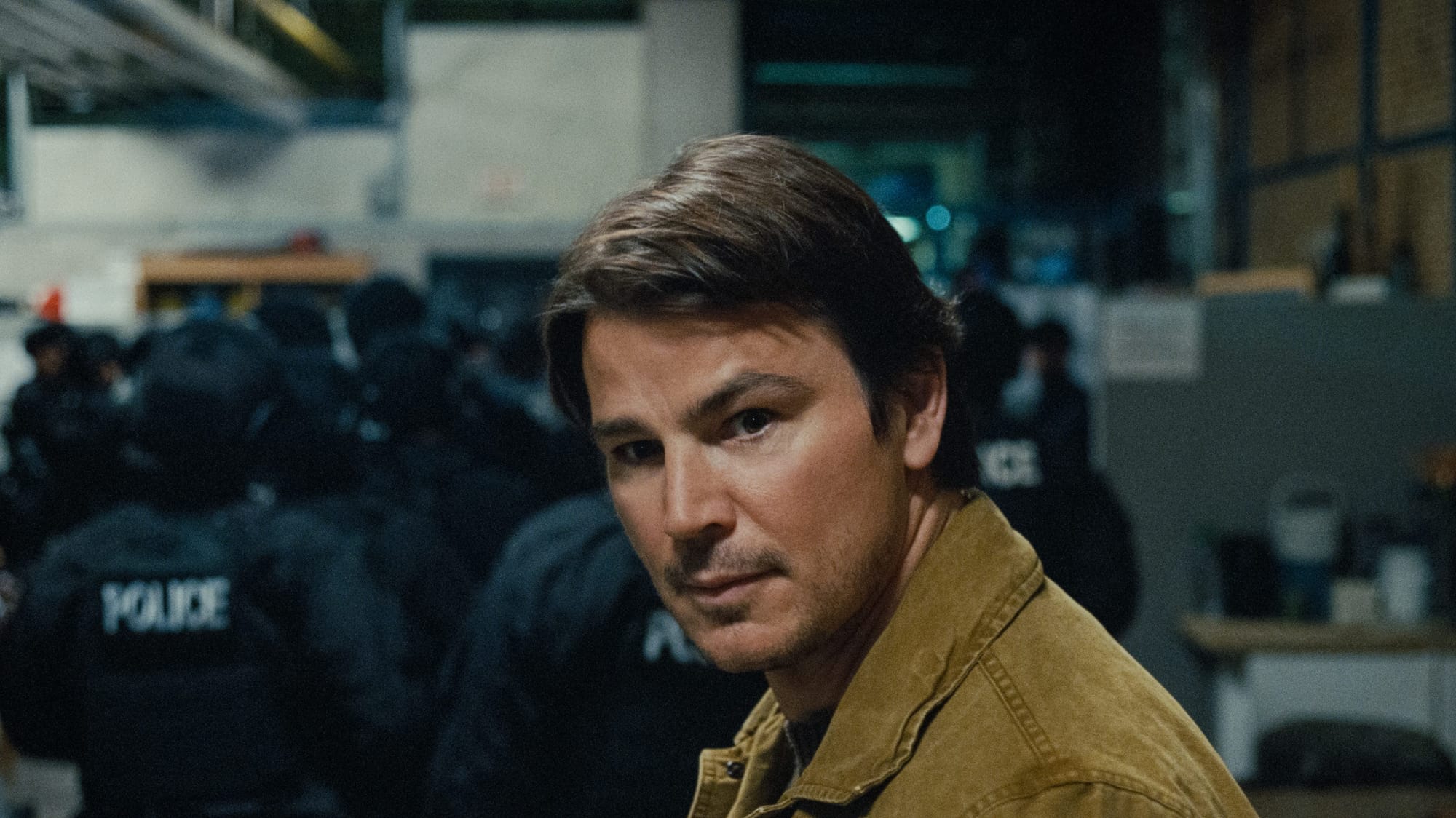

By contrast, when a movie this year actually looked like it was produced in the physical world it provided inordinate pleasure - one of the more striking illustrations of how cinematically bereft we are. M Night Shyamalan's Trap had me delighted for days, its cat-and-mouse mechanics executed with what used to be basic competence, but is now master craftsmanship. Trap felt more like what Tom is fighting for.

AI isn't just evident in aesthetics. So-called theatrical releases are being created, presumably still by humans, with a streaming algorithm mentality: present your mission statement within the first five minutes or risk the audience's return to the main menu. Thus we have a culture of tonal monotony, movies that tell you what they are in their opening seconds and proceed to hold that vibe for their duration, operating from a position of terror that if there's a bump, a deviation of any kind, we'll turn it off. Never mind that, in a cinema at least, people who've bought a ticket will more than likely stick around, regardless of how baffled they are.

Longlegs was the horror success story of the year, and it led the way in the monotony stakes. It’s an embarrassingly overrated movie that maintains such a stringent tonal adherence (let's trademark it "dread slurry") it becomes its own form of wallpaper, a tedious hybrid of video game cut-scene and desktop screensaver. Its performances and stylistic trappings are in complete, inexorable machine-like synchronisation. It should have played in cinemas on a continuous loop - you could start or finish it at any point in its runtime, take a break, check your feeds and come back whenever. Don't worry, you wouldn't miss a thing.

This year of AI peaked with Jeff Nichols' The Bikeriders, a throwback mid-budget period melodrama of the kind that, once upon a time, was Hollywood's bread and butter. It was apparently shot on film, though the degree of Instagram-filtering applied to the movie makes that assertion meaningless; it looks and feels like any other piece of video content you might ignore as you walk past an Urban Outfitters storefront.

The prompt that generated The Bikeriders was almost certainly "Goodfellas on motorbikes mid-60s". This is evident from the film's opening, which cannibalises the Scorsese touchstone wholesale: a shorthanded sequence of snazzy violence that ends with a freeze-frame as voiceover kicks in. "I've had nothing but trouble since I met Benny,” twangs Jodie Comer, in her ludicrous attempt at a Chicagoan accent. I had nothing but trouble with the subsequent 110 minutes. Mostly I wondered how the director of Shotgun Stories could let such drivel out the door.

I left the cinema deeply depressed. Justine Bateman's prophecy was coming true - AI isn't being met with resistance because we're already accustomed to it; our shit is no different to its shit.

Less than 24 hours later I was revived by Alice Rohrwacher. La Chimera would have been revelatory in any year, but in 2024, the morning after The Bikeriders, it was miraculous. Admittedly I was vulnerable and primed to receive it. But its relentless invention, its wit and brio, its coughing grimy shanty-town grave-plundering energy, its heart and soul, were a balm. Finally, a movie.

And there were others. Exhuma and Evil Does Not Exist have stayed with me. Both are bold, singular entertainments with plenty going on under the hood. Both also feature extended, tour-de-force centrepiece sequences, which are so different as to be incomparable other than to say they’re magnificent. The former’s outrageously frenetic exorcism Korean-style is a visceral, relentless showstopper; by contrast, the latter’s developers-vs-locals town meeting is so effortlessly masterful it felt as if I was witnessing it live. Lightning in a bottle, as they say.

It was serendipitous that Francis Ford Coppola released his private megafolly in 2024. After a hard slog through so many imitations, so many movie-like products, Megalopolis asserted itself as a huge, hail-Mary hot mess you couldn't help but love, sublime because of how much of it is completely fucked up (and how much isn’t!). It's telling though - or maybe tellingly human - that despite being about vision and creation, Megalopolis' most visionary scenes were about venal rich folk playing their power games. The bits depicting Adam Driver's engineering of the titular paradise were hollow, cheap and cheesy, and - also tellingly - dependent on third-rate digital effects.

Way back in January I saw another Adam Driver movie which, while failing at many other things, captured the thrill of creation much more convincingly. Midway through the Ferrari biopic, Driver's Enzo is at the kitchen table with his young son Piero, poring over mechanical blueprints. This kind of scene is hard to pull off, but with only those sheets of paper and a few broad strokes of dialogue at their disposal Driver and his director Michael Mann conjure a palpable frisson, the allure of discovery, of mastery. It shouldn’t work, but the impossibly delicate combination of performance, lighting, sound design and everything else - including, I would argue, luck or fate - mean that it does. Poetry still eludes AI, or indeed any of the humans doing the AI thing. Enzo demonstrates how a new component will work better than its predecessor. Piero observes that the drawing itself looks cool. "In all life," Enzo replies, "When a thing works better, usually it is also more beautiful.”

-Dan Kircher.

Dan Kircher is a film editor based in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. He cut Michelle Savill’s Millie Lies Low (2022), Ant Timpson’s Come to Daddy (2019) and David Farrier’s Mister Organ (2022). He most recently cut Timpson’s Bookworm, a crowd favourite at festivals in 2024.

Dan’s work has played at international festivals including SXSW, Berlinale, Tribeca and Toronto. His other credits include teen thriller The Changeover (2017), te reo Māori martial arts adventure The Dead Lands (2014) and the Royal New Zealand Ballet’s film production of Giselle (2013).

David here again — what did you think of cinemas in 2024?

I’m curious to hear what you Worms have been watching in cinemas (and on, sigh, laptop and phone screens) this year.

Did you hate something everyone else loved?

Did you love something everyone else loved?