There was a death last week, and it was me

DJs came for me, and only a corpse remains. Which got me thinking about, well, death.

Hi,

There was a death last week, and it was me.

That is if death was possible due to excessive angry DJs and DJ fans messaging me on every format known to humankind:

The messages were in response to the Webworm I’d written last week, which contained the most provocative headline I’ve ever penned, or will ever pen: ‘Are DJs worse than Covid?’

Things were made worse when Stuff republished my piece, reaching a fresh audience of DJs unaccustomed to my ways (that sometimes, just sometimes, I am having a little laugh). The headline then went viral on accounts like @bedroomdjfantasties and it all just accelerated from there.

As you may recall, the piece was about the British DJ who’d decided to forego his final day of self isolation and hit the clubs. He tested positive for Omicron shortly afterwards.

The overall point of this article was the fact the virus relies on people not following the rules in order to spread. Ergo, the host is more culpable than the virus.

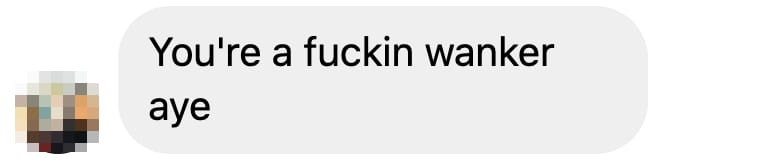

However my headline (meant as a bit of a lol) was taken as a personal attack on all DJs, as was the part where I called DJs “international laptop users”.

I was rightfully slayed by a variety of DJs who pointed out that I am also a laptop user, a point I simply can’t argue with. Although if I was going to argue I’d say I occasionally do get out from behind the laptop and made documentaries and podcasts.

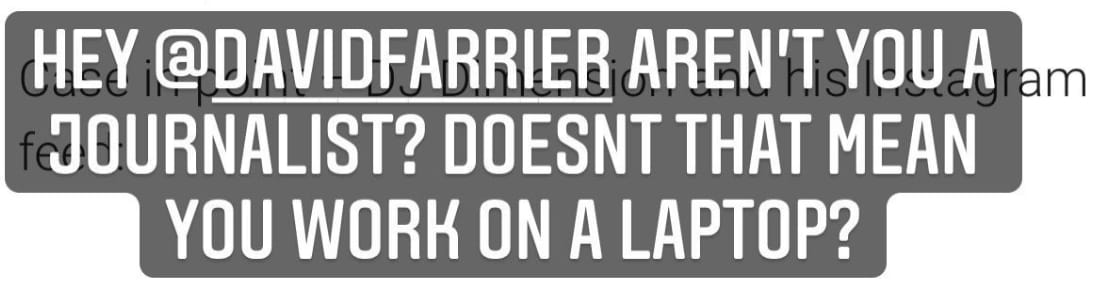

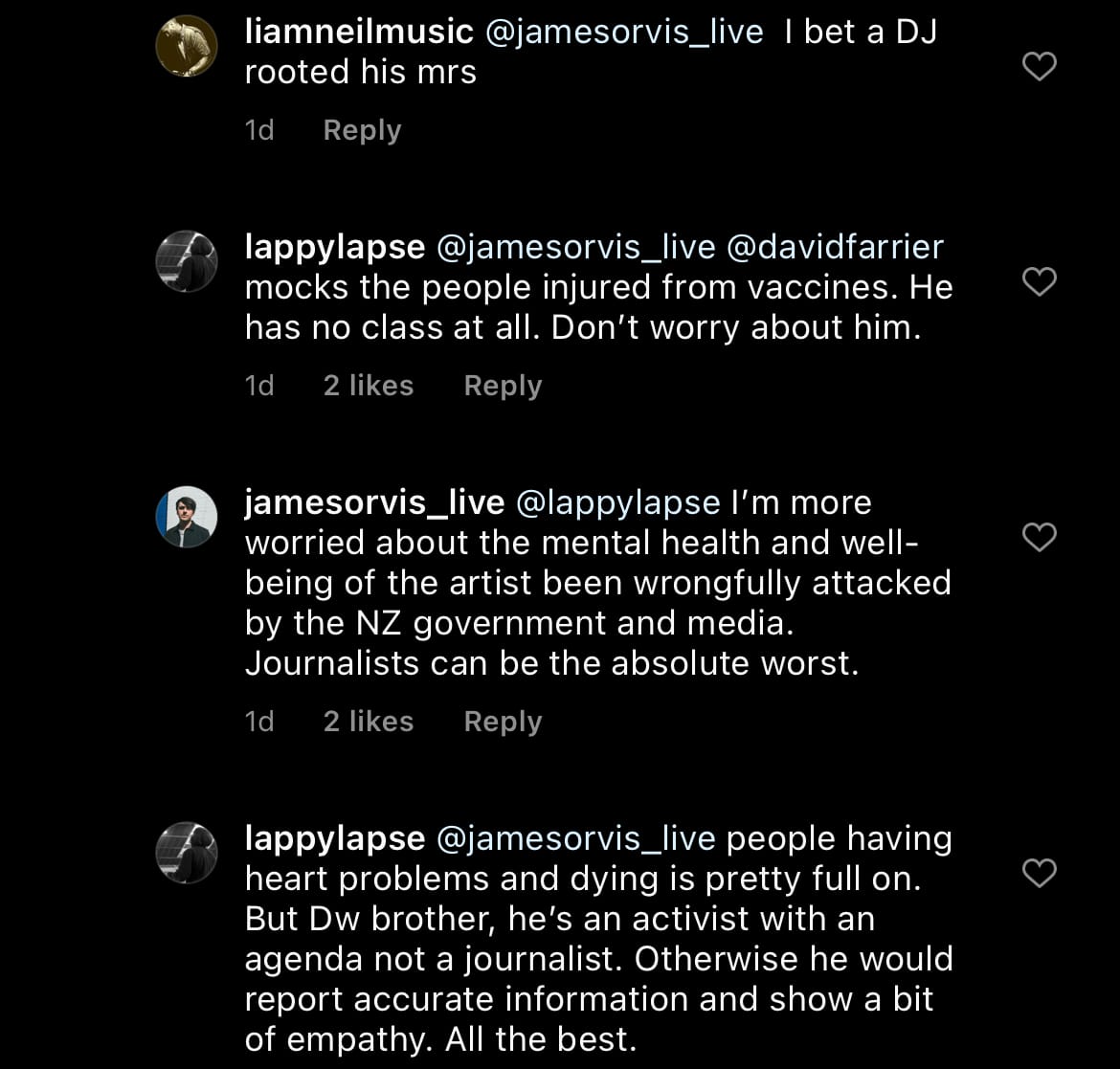

Some DJs took a more creative route and suggested a DJ had had sex with my girlfriend, before suggesting DJ Dimension had been “wrongfully attacked” (he wasn’t attacked, and the facts about him were correct) and that alleged widespread vaccine injuries were real (a strange tangent, but of course we’d end up there).

For the record, I don’t hold any grudge against DJs — it’s a talent I don’t have, nor will ever have. I forget sometimes that an attack on something you genuinely love can hurt. You want to defend the thing that makes you get out of bed in the morning.

Journalists are actually one of the most guilty groups at taking their job too earnestly. Hearing us talk about our jobs you’d think we’d just parasailed in and saved a dozen children from a raging house fire.

So from one laptop user to another: It’s okay. We’re okay.

This is a bit of a crude transition, but I started this piece by saying “There was a death last week, and it was me.”

I meant that in a metaphorical sense of course, but death is what I actually want to write about.