6 Months of Madness to Prove NFTs are Hell

Artist Joshua Drummond has created a fully functioning NFT project to prove NFTs are utter garbage

Hi,

Just quickly — I was overwhelmed by the comments under my face-blindness newsletter last week. I’m working on a followup that digs a little deeper, because your feedback blew my mind.

But today, Webworm presents an art project so intense and weird I don’t really have words to describe it. It’s from Joshua Drummond, who wrote an incredible piece last year on being trapped in a system that won’t let us act sanely against climate change.

He followed that up in February with a stinging attack on NFTs, which he called ‘Needless F**king Things’. He argued that NFTs were to be sent to death row, their life extinguished on old sparky.

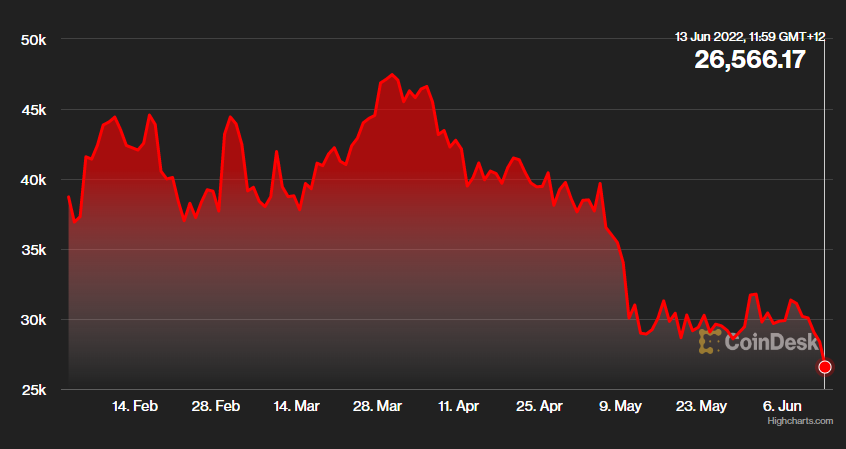

Of course news about NFTs has raged on since he wrote that, while crypto-currencies like Bitcoin have done this:

Josh finished his piece back then with a vague threat. Actually, it was a very specific threat:

“So I’m trying […] the biggest project I’ve ever attempted. I’m taking everything I’ve learned about NFT success and applying it to the most popular thing I’ve ever made: my paintings of birds wearing hats. And along the way I hope to either:

a) help prove NFTs are mostly useless for artists, or

b) eat humble pie and admit NFTs are great, actually.

The price of this humble pie? It starts at the low, low cost of… my mortgage.”

I read those words — and I published them. But I didn’t think Josh would actually go through with it.

But over the last six months or so, Josh has gone and built his very own NFT infrastructure to make a point.

As in… you know how ‘Bored Ape Yacht Club’ is a thing? He’d gone and done that. All of it.

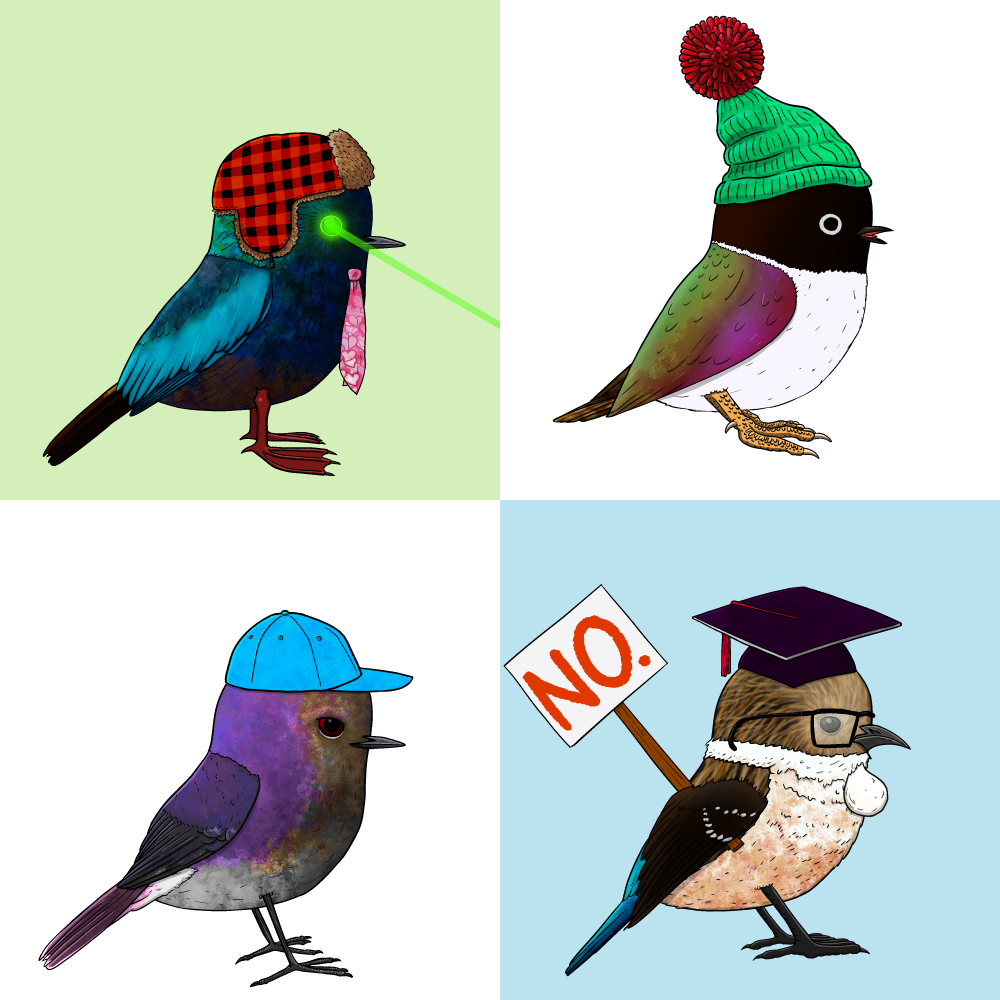

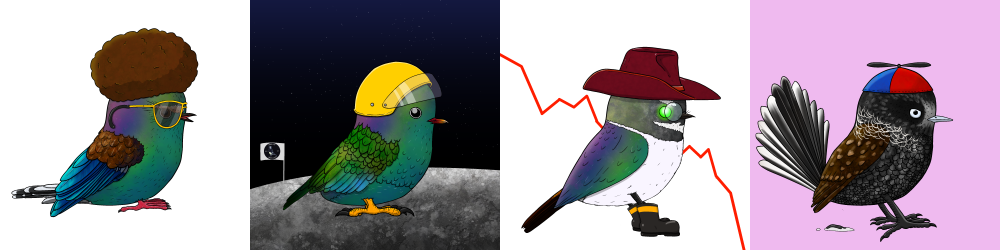

He’s made generative artwork of ten thousand hat-wearing birds (each with its own name and story), a site to mint them into NFTs, an absurd trailer for an awful videogame that’s actually playable, and an entire website that explains the whole ridiculous thing.

It’s like an ultra-postmodern interactive art exhibit pulling together all the madness of NFT culture. The whole thing is batshit insane, and I feel lucky to share this ridiculous thing with you. Josh has really poured his heart and soul into this thing.

Strap in. I’ll let him explain.

David.

Welcome to The Bird Hat Grift Club

by Joshua Drummond

A few months ago I finished a Webworm deep dive on NFTs with a promise to start my own non-fungible token project, and the ominously optimistic words “Happy bidding.”

Since then, crypto has been absolutely munted. Here are just a few highlights:

- Bitcoin is crashing

- Ethereum is crashing

- The Terra stablecoin project — formerly one of the top ten cryptocurrencies — crashed, to the point that it became worthless overnight

- Dogecoin founder Jackson Palmer called crypto a grift

- The Sex Pistols shot out NFTs, killing irony dead

- A Kiwi guy from Hamilton called Martin Van Blerk created an NFT videogame project called Pixelmon that reeled in a staggering $104 million NZD. Then the art was revealed to be comically bad, and the scheme crashed

- Madonna collaborated with Beeple to create (wildly NSFW) NFT videos of robot centipedes emerging from her digitised vagina, which — despite everything — is still a surprising sentence to find yourself writing.

But, true to my promise, I’m getting in on the NFT craze — about 12 months too late, at the worst possible time. It started out as an attempt to make a silly joke, and ended up as hundreds of drawings, deep dives into the weird world of AI and procedurally generated art, and thousands of insomniac hours spent on… well, it’s still a silly joke.

In the process, I’ve managed to make something I don’t think anyone else has: the first-ever anti-NFT NFT art collection; an NFT-based attempt to sell no NFTs at all; a project designed from the ground up to fail.

The original idea was simple. I’d follow up my Webworm article by putting some of my original Aotearoa Birds (In Hats) paintings, still the most popular thing I’ve ever made, on NFT marketplace OpenSea. I’d list the cheapest one for the approximate equivalent of my mortgage debt and scale up exponentially from there. By creating the “world’s most valuable NFT collection” I hoped to get a sniff of attention from the mainstream media (which is still incredibly credulous about all things crypto). No-one would buy them, but I’d have fun writing about it, readers might enjoy a gentle chuckle, and I’d maybe sell a few tea towels.

The trouble started when I saw there were already two variations on the birds-wearing-hats theme on OpenSea. That’s fine — the idea of birds wearing hats has been around forever. But it meant that I couldn’t call my NFT’d original paintings Birds in Hats, or they’d get lost in the shuffle.

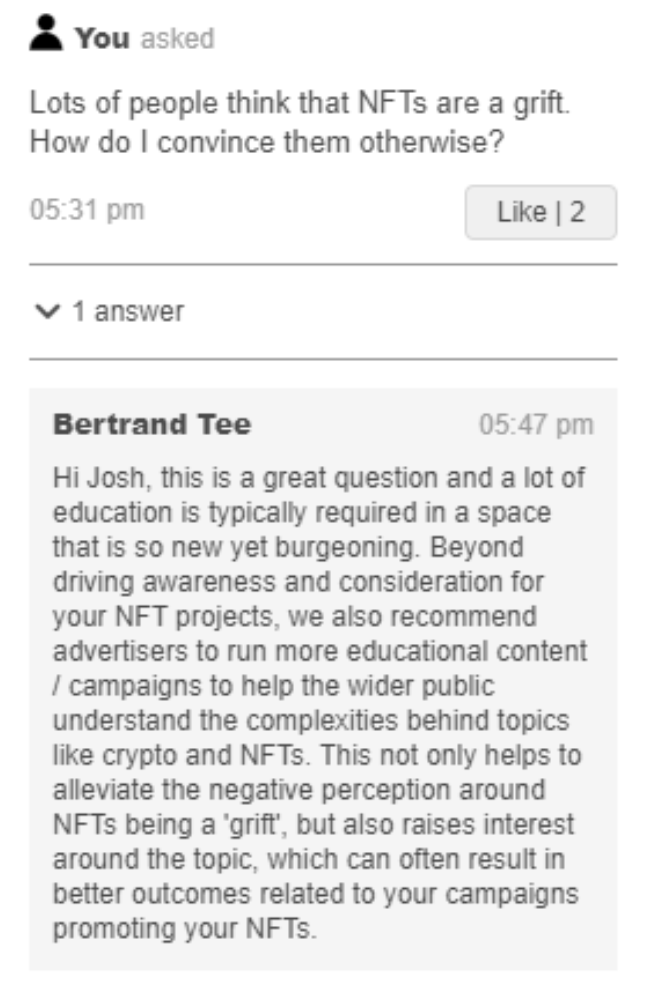

Around this time, while I was having a nice quiet evening doomscroll, an ad caught my eye. I was invited to an official Twitter webinar, where I’d be told all about how to use the platform to huck NFTs! I signed up immediately.

This was a terrible mistake. The webinar was more boring than a tunnel to the centre of the Earth. I whiled away the aeons by asking asinine questions, and was surprised to get an answer.

My plan came to me in a blinding flash of idiocy. I would take Bertrand’s helpful suggestion, and do the opposite. Instead of alleviating “the negative perception around NFTs being a ‘grift,’” I’d embrace it. Grifting would be right in the name.

I decided to model the format of the infamous Bored Ape Yacht Club, with the key difference that my NFT scheme would be designed to showcase how ridiculous NFT schemes are. I’d make 10,000 NFTs of birds wearing hats, and do my best to sell none at all. And, of course, I’d call it….

I figured it’d take a week or two.

So far, it’s been just over six months.

An AI interlude

If you’ve been near the internet lately, you’ve probably seen the viral trend of making cursed images with a tool called DALL-E Mini. I love to see it, I’ve enjoyed making weird shit with AI for years, and I thought I’d be able to quickly smash out an NFT collection by training up a dubious Russian instance of DALL-E on my artwork, and getting it to paint birds in hats for me. Boom, job done, NFT collection launched, laughs all round.

There was just one problem: the AI I used doesn’t know what birds are.

While DALL-E is great at reproducing internet favourites like cats and dogs, when you train it to make birds, the results are… really something.

Here’s my original art that I trained the AI on:

What it made was the stuff of feathery nightmares, full of muffled cooing and terrible malevolence.

I watched in horror as the AI chundered out hundreds of eldritch horrors, and knew in my soul these birds were beyond cursed. They were evil. I shut down my DALL-E instance, consigning a potential infinity of demonic birds to digital death, without regret. There was no way I could unleash this on the world.

This left my project in limbo. Despite hours of work, and roping in much smarter friends to help, the AI birds remained hideous. Of course, NFT art is infamously bad. But it’s not usually this terrible, and I’m driven by a futile desire to make good art. I couldn’t stand the thought of rushing out yet another ugly NFT collection to make fun of ugly, rushed NFT collections. If I wanted to strike the right balance between cute and cursed, I’d have to do it the old-fashioned way, and draw it myself.

How long might that take? I researched a few NFT collections to get an idea. The best and most successful ones were made from hundreds of different elements, layered together by a computer program.

I realised three things: that continuing this project would be monstrously hard, that it would take an absurdly long time, and that I was going to do it anyway. I would create the best goddamn NFT collection it was in my power to make, and then do my best to make sure no-one would buy it.

How the NFT art sausage is made

Before I go on, I need to explain how most NFT collections come together. Much like a sausage, “generative” art is a collection of hacked-off bits, all smushed together. You know those paper dolls you’d sometimes see in cut-out books for kids, or on the backs of cereal packets? You cut out the doll shape, then the clothes, and mix and match however you like.

Generative art is like those paper dolls, but digital. It’s a bunch of PNGs, digital images that can preserve transparency, layered on top of each other. In generative art, there can be anything from a dozen to several hundred potential layers, called “traits,” for a program to choose from. Here, I’ve made a gif that I hope will save me typing another thousand words:

The difficult part is, the more elements you create, the harder it is to make sure they all work well together. It gets more technical, but all you really need to know is that I needed to hire a developer (who I’m paying in photo-realistic chimpanzee paintings) and do a hell of a lot of drawing to make this thing work.

How much drawing? Put it this way: before I started work on the Bird Hat Grift Club, the only artwork I’d managed to do for an entire year was several illustrations for my Webworm newsletter on climate change.

Now, I found myself spending every spare moment drawing birds and hats, for an art project I’d designed to fail, based on a technology I hated. Why was I so compelled to do this? Sitting at my desk late at night, slugging out yet another wing or beak or random bird bit, I figured it out. What I was feeling was joy — the sheer joy of play.

Being diagnosed with ADHD at 38 years old (with a bunch of autism spectrum traits thrown in) was a mixed experience for me. On one hand, it cast a clarifying lens over pretty much my entire life to date. It explained why I found some hard things so easy, and many easy things so hard. On the other hand, it felt like a curse. My desperate hope that I’d one day find a fix for the distractibility and procrastination that’s plagued almost everything I’ve ever done was dashed. I knew now that I was wired differently, that I was decidedly non-neurotypical, and that certain things would always be difficult.

But with this pointless project, all the brakes were off. It wasn’t going to work, so I could do whatever I wanted. It had been a long time, perhaps years, since I’d indulged my own weirdness, since I felt the visceral pleasure of scratching a truly compelling itch. I found myself making excuses to draw out the project, the scope creeping ever further, incorporating every half-baked shower-thought. “Just one more hat,” I’d tell myself, and draw five.

How bad did it get? Well, the biggest NFT collections like the Bored Ape Yacht Club comprise about 300 unique elements.

The Bird Hat Grift Club has over 450 unique elements, and I drew every single one. And I did a lot more besides.

An ironically bad project that, ironically, I’ve put way too much effort into

Every single aspect of the Bird Hat Grift Club has been engineered to be at least as good as, or better than, the big market-leading NFT projects.

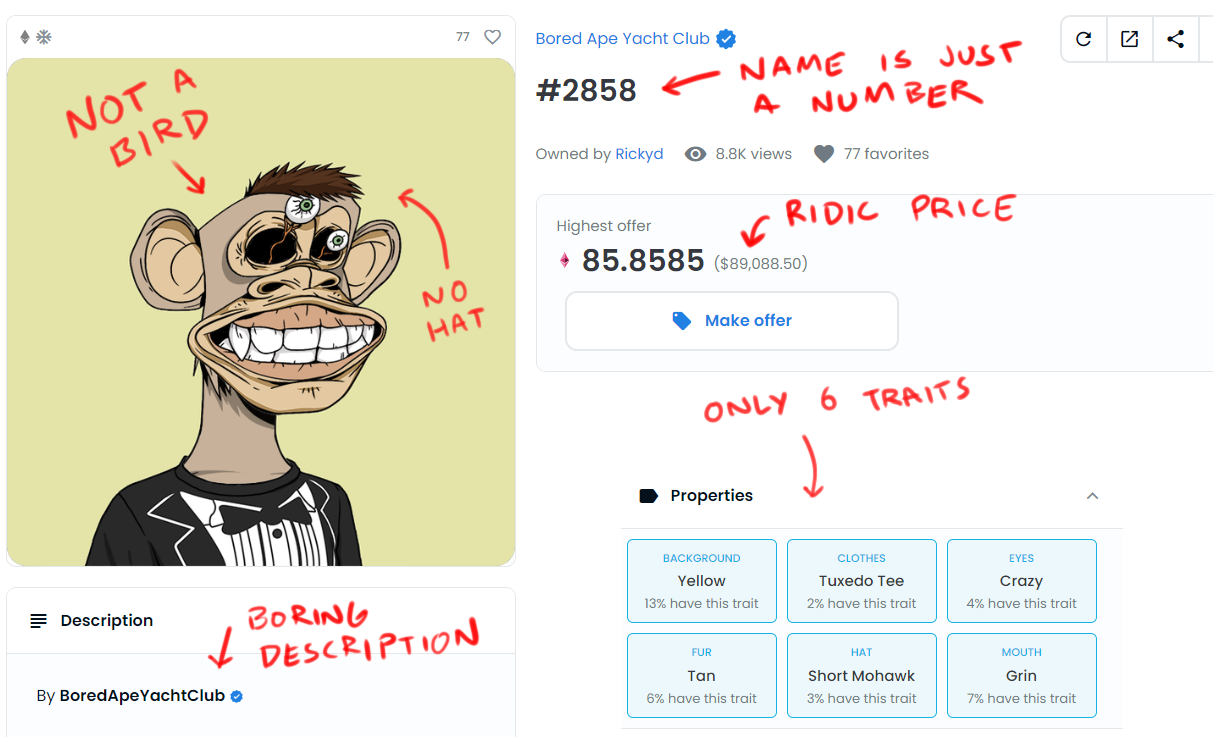

Look at this Bored Ape Yacht Club listing. I’ve noted some of the problems with it in red:

The name is just the collection number, #2858, and the description is the boring-ass “Created by BoredApeYachtClub.” To me, that’s just dull. I figured I could do better, so I did.

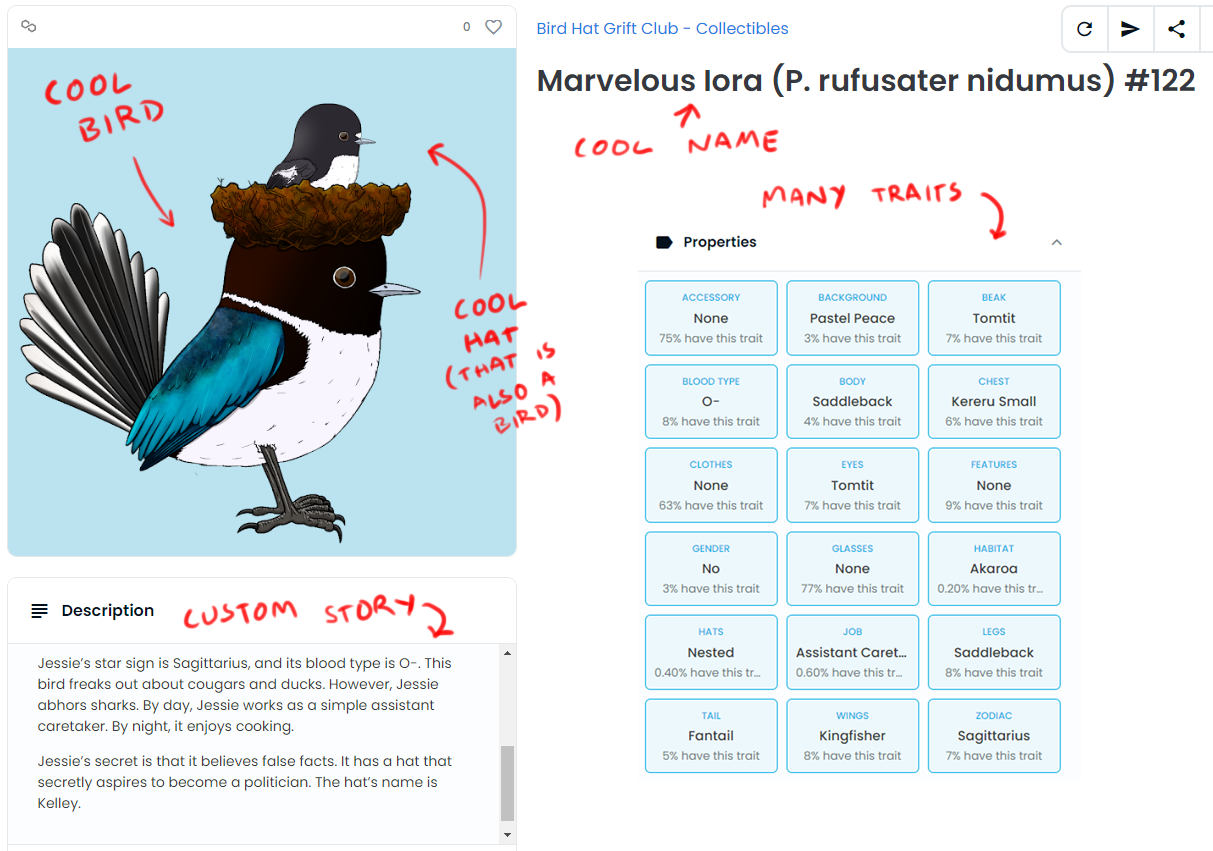

Every single bird in the Bird Hat Grift Club, both Originals and Collectibles, has its own completely unique name and story, either written by me, or generated by a program that does a mad-lib trick to fill in a bunch of programmatic blanks.

Here’s the result:

It keeps going. There’s nothing in this project I haven’t tried to overkill, no dead horse left unflogged. NFT projects have roadmaps — a kind of wish-list for the project if funding goals get met, assuming the pseudo-anonymous founder doesn’t disappear into the ether with the community’s money. Most NFT projects have just one roadmap. Mine has three. Does your favourite NFT project propose to purchase its very own politicians, fix my gutters, or send an actual NFT to the actual moon? I didn’t think so. But mine does.

“Is there a videogame on your roadmap?” I hear you ask, breathless with excitement. Of course there is! Lots of NFT projects come with absurdly over-hyped promises of a ground-breaking videogame metaverse that turn out to be absolute dogshit. Well, the Bird Hat Grift Club already has a videogame, and it’s as least as good as any other NFT game. You can even play it!

As for hype, I humbly submit that no-one will ever be able to beat what my incredibly talented friend FlashMedallion and I have created. Behold: Bird Hat Grift Club: The Game: An NFT-Powered Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Combat And Dance Simulator Metaverse (BHGCTGANFTPMMORPCADSM, for short)

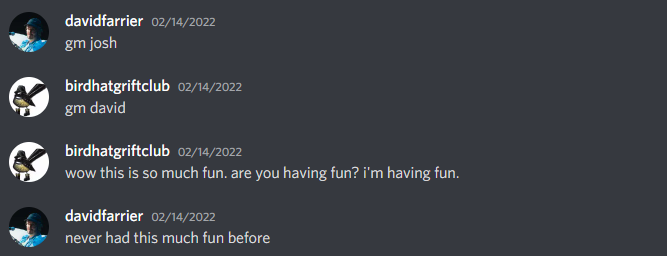

But wait, there’s more. We have a Discord server! Of course, pretty much all NFT schemes have a Discord server, and pretty much all of them are unrelenting tedium only briefly punctuated with the excitement of being scammed. But they don't have David Farrier, and they’re not having as much fun as we are.

That’s just a glimpse of the action awaiting you in THE BIRDHOUSE, our very own grifting hub. Join us now!

Are you for real? And what do you mean when you say it’s “built to fail?”

Yes, I’m for real. It’s a real NFT project. You can really mint Bird Hat Grift Club NFTs. (To be clear: do not do this.)

But why am I going to all this effort when I think NFTs are terrible and don’t want you to buy them?

It’s basically this: I think there are better ways of supporting artists than indulging in a ponzi scheme created to sell crypto, including things like:

- Buying original art

- Buying reproductions of art, like PDFs, or prints

- Subscribing to an artist through a service like Patreon (or Substack!)

- Commissioning custom artwork

- Crowdfunding special projects

The point of the Bird Hat Grift Club, apart from having fun, is to encourage people to support art in these non-NFT ways.

So here’s how it works. For everyone that supports my work in a non-NFT way, I’ll remove a bunch of NFTs from sale, and they’ll never come back.

(And anyone who does this gets a bunch of the cute/cursed bird images and stories that would have otherwise been sold as NFTs.)

And then there’s the alternative.

In Part One, I talked a lot about how everyone has their price, and that’s still very true. But it turns out my crypto price is very expensive. My Original NFTs start at the Ethereum equivalent of $250k in cash and go up to a nice $100,696,969.00 dollars. The Collectible NFTs have a mint price of 4200 MATIC, which (at the time of writing!) is about $1800 NZD. At those prices, I think it’s unlikely that anyone will ever buy my NFTs, and it’s much cheaper and easier to support my work the old-fashioned way, at a discount of about 99.99%. That’s better than a sale at Briscoes.

But here’s my message to any NFT stans reading this. If my plan fails successfully, the supply of Bird Hat Grift Club NFTs available to mint will quickly drop. And you know what that means: FOMO — the most powerful motivating force of late-stage capitalism. If you are thinking about buying one of my NFTs, you’d better be quick.

There’s another powerful force at play: the zeal of the convert. I’ll happily sing the praises of NFTs if they end up making me millions of dollars. That’s money I can use to have a lot of fun with a community that wants to do good in the world. The benefit of selling NFTs will have well and truly outweighed any downside, and you, NFT enthusiasts, get the incredible story of a reluctant convert to NFTs as a marketing tool. Don’t take my word for it — just ask the world’s greatest marketer and founder of Christianity, Apostle Paul.

“Wait,” you think, “wasn’t Christianity founded by Jesus?” Nope! Christianity started as one of many small messianic cults, and old mate Paul was dedicated to destroying it. Then he had a seizure on the road to Damascus and did a U-turn. His innovation was to take a new, extremely Jewish minor religion, and open membership up to anyone at all. The new craze spread to Rome and the rest, of course, is history. Nothing sells like a conversion story.

Just think, NFT enthusiasts — I could be your Paul, because right now I still hate the needless overhyped fraud-ridden exploitative environment-killing ugly fucking things.

But really, why?

If this project succeeds by removing all the NFTs I have available to mint, thanks to people purchasing art, prints, Patreon memberships, commissions, and more, I’ll have made enough (real) money to do art full-time for at least a year. That’s dream-come-true material. Instead of doing projects like this one in my vanishingly-spare time, I’ll be able to devote my working life to it. I’m also doing it to draw attention to another problem: the potential extinction of artists.

Just like many of the birds I’ve drawn, artists risk becoming an endangered species, and they need support. Part of it is the present economy — working artists are always among the first to suffer when the almighty market has one of its funny turns — and things were already hard.

Working artists are routinely exploited. Whether it’s through Karenesque requests to provide free labour “for exposure;” corporations dreaming up competitions that are actually demands for “spec work,” or random weebs demanding drawings of an anime waifu for free, there is a strange cultural expectation that not only should artists work for a pittance; they should appreciate whatever dry bones are thrown to them.

I’m intrigued by the dissonance between how art is regarded as a rare and magical skill that can’t be acquired by normies, and (often simultaneously) as a disposable skill that isn’t worth paying for. Both these views are wrong. Nearly anyone can learn to draw and paint, and yet those skills are hard-earned and should be fairly compensated.

In my mind NFTs may have one truly useful thing going for them: a mostly-unrealised potential to reward artists for their work. Sadly, the work-for-hire artists behind many top-selling NFT collections often receive a fraction of the revenue their creations generate, but it’s still worth highlighting the extraordinary prices that NFTs fetch, compared to skilled work that’s not linked to a blockchain. There is a massive discrepancy between what people will pay for one randomly-generated profile picture NFT (sometimes the equivalent of many thousands of dollars) and what people will pay for one genuinely unique artwork (many will baulk at paying fifty bucks for a painting that might have taken hours, days or weeks). It’s bonkers.

The other risk to artists comes back to AI.

We’re all having a lot of fun getting AIs like DALL-E to draw cursed birds, or these extraordinarily accurate pictures of David Farrier that I got my AI to make when I got frustrated with its avian output — but, even as we giggle, AIs are getting geometrically better at drawing things.

Very soon, AI will be able to create photorealistic, congruent depictions of pretty much anything a user enters in a text prompt, in any style desired. The extraordinary ethical and moral implications of this are outside the scope of this article (maybe I’ll talk about AI ethics another time, because boy is it problematic) but the hard fact is: the world is run by accountants. Any corporate bean-counter will look at the high cost and long lead-times for getting a working artist to make something, compare it to the cost of getting AI to make it in thirty seconds, and make an easy decision.

Artists who want to keep working will have to figure out new ways of doing things. I think that’ll include learning to work with AI, and creating communities and support structures. If artists start doing this now, maybe we’ll be ready when the revolution comes.

My request for Webworm readers — apart from, obviously, sharing this newsletter with your friends, and inflicting it on your enemies — is to adopt an artist. If it won’t cause you financial harm, give them real actual money. It doesn’t take a genius to predict an economic shitstorm when it’s already pissing down, and with the way the winds are blowing, a lot of artists are going to get hosed. Consider decoupling your wallet from the entertainment-industrial complex (Walt Disney does not need your money) and instead supporting an artist, or an artist collective. If you’re not financially up to it, that’s OK! Instead, share artists' work far and wide, and make sure they’re credited. Join their communities. Even just do the old Like and Subscribe. It all helps.

So, there you have it. The Bird Hat Grift Club is an contemporary art/NFT project designed to showcase the futility of NFT projects, to highlight the plight of artists, and to make me giggle over and over again at randomly-generated birds that strike just the right balance between cute and cursed. If I’m lucky, and enough people support me, it might just help me turn art into a job. And if the world’s even madder than I think it is, and people actually buy the NFTs I’m selling? Well. The moon’s the limit.

Happy buying. Whether there’s a Part 3 of this story or not… is up to you.

David here again. I know that was a lot.

Josh’s site is now fully online and functioning — The Bird Hat Grift Club. It’s a place you can explore Josh’s work, and proof he’s actually done all this. My brain still can’t quite grasp it. There really is a videogame.

Mainly his site is a good place to marvel at how ridiculous the whole thing is.

You can also support Josh’s work, and wipe a few NFTs from the face of the Earth. I love Josh’s stuff, and have just picked up a few of his prints.

To be honest, part of me hopes his utterly ridiculous anti-NFT-NFT project goes viral on Reddit, or that some tech billionaire shares it in their group chat, and suddenly Josh becomes an insufferable millionaire. It would serve him right.

David.