Dylan Attempts to Stop a Pig Butchering

Pig butchering scams, big and small, are on the rise.

Hi,

When I look back at my history with Dylan Reeve, it’s pretty unusual. We first met in the pool at Kim Dotcom’s mansion, as helicopters buzzed overhead and secret service agents flung themselves off the side of his house, abseiling to the ground with guns drawn.

Kim Dotcom was a German hacker and (computer) pirate, who’d set up base in New Zealand. He ended up releasing a badly produced techno album and started a political party named after the Internet. At some point in the mix, 90 New Zealand police officers raided his house under direction of the FBI, angry he’d been pirating movies like Lord of the Rings on his MegaUpload service — alleging he was involved in racketeering and money laundering.

(Just to show how small New Zealand is, that mansion is now occupied by Webworm regular, billionaire Nick Mowbray.)

The day Dylan and I found ourselves in Kim Dotcom’s pool wasn’t the actual raid, but at an event he held for the media about a year later, in which he hired an array of helicopters and actors to reenact that fateful day in 2012.

It was one of the weirdest days of my life.

Dylan re-entered my life a year later, when I’d begun to investigate what appeared to be a strange scam called “Competitive Endurance Tickling”. I’d written a blog about it, and he’d reached out with some more information after doing some further online sleuthing. A month later, we met at my flat, ordered pizza, and discussed setting up a Kickstarter to fund an investigation.

That investigation eventually turned into a feature length documentary — a film that never would have existed without Dylan. He unearthed shit online in a way I’ve never really witnessed before.

Ever since those Tickled days, Dylan and I talk pretty much every other day online — and Dylan continues to do what he’s always done: Help people navigate an increasingly confusing, deeply strange online world.

And recently, he came face to face with a pig butchering scam. And it was a rare case where he felt utterly helpless.

David.

How Do You Help A Scam Victim Who Doesn't Know They're A Scam Victim?

by Dylan Reeve

A few weeks ago, on my regular trip to the local library with my wife, I saw something I’d never seen in person before — someone in the middle of being scammed.

As I headed toward the back corner of the library to return last week’s books, an older man at a nearby table caught my attention — with a small, slightly hunched, stature he wore a cap that covered what I assumed was a balding head and was dressed in a simple dark sweater and pants — he was what you might describe as unassuming. Like your friend’s granddad. Or, frankly, a number of the staff at the library itself.

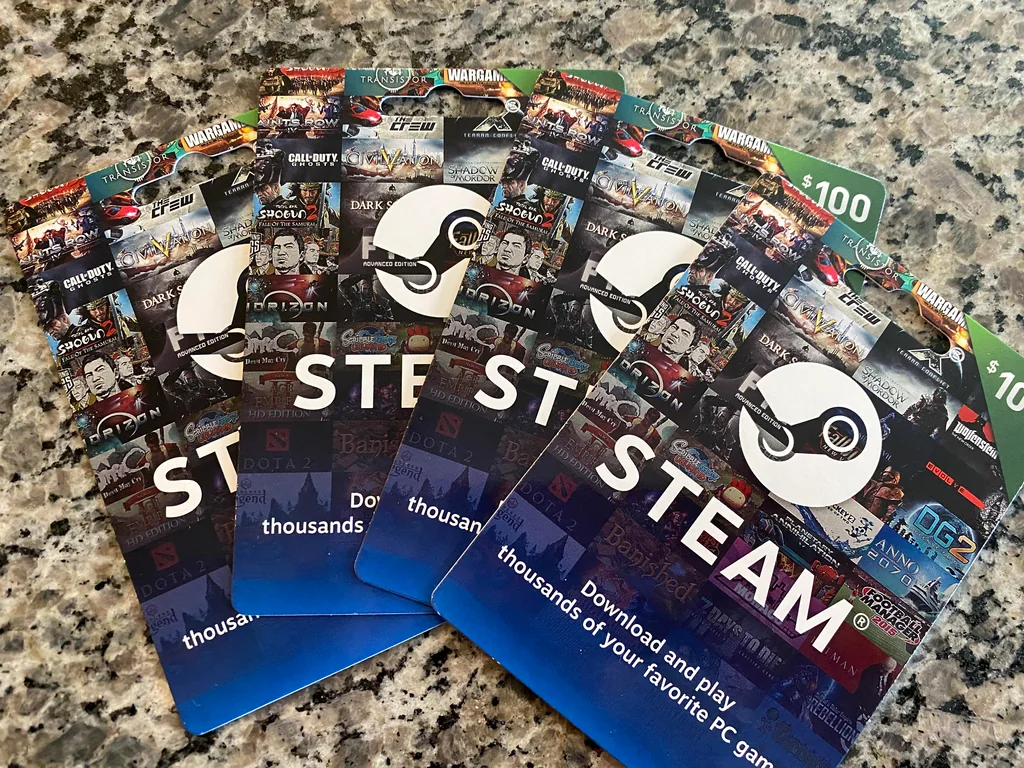

So really, it wasn’t him that grabbed my attention, it was the array of Steam gift cards spread out in front of him.

I watched him briefly as I slid books through the return slot. He was meticulously working his way through each of the cards in front of him — scratching the panel on the back of each card that reveals its activation code, then taking a photo of the card with his phone before sending the photo to someone on Facebook Messenger and moving on to the next.

What I recognised immediately in that moment was the mechanics of a common scam where victims are encouraged to purchase some sort of non-cash prepaid gift card and provide the details to scammers. In the case of Steam — an online computer gaming marketplace — the gift card codes are either used to purchase fake games from the Steam store (which have been created by the scammers solely to launder the money) or the codes are offered for sale at below face value via online marketplaces or websites.

Without a bank involved there is little a victim can do to claw the funds back, and there’s no fraud department or curious tellers to worry about. Instead a victim simply walks into a retailer and pays hundreds of dollars for whatever gift cards are demanded by the criminals that are exploiting them.

With all this knowledge in mind, I approached the guy at the table and politely interrupted. “Hi, sorry to bother you,” I began. He paused and put his phone down, so I continued. “I was just wondering what you were doing with all those Steam cards. I only ask because I buy them for my kids sometimes, and wondered if you were doing something similar?”

He looked at me for a moment. “They’re for a friend.”

A friend that I could see was messaging him after each photo he sent, with replies such as “thank you darling.”

I continued, trying to avoid being confrontational with a man I’d never met before. “Oh great, I only asked because I was worried for a minute… this is the sort of thing that scammers often ask people to do,” I offered.

“It’s not that,” he replied, somewhat defensively.

It definitely was that. But I didn’t want to be a dick about it.

I explained a little more that I was a journalist who sometimes wrote about these sorts of things, so I was naturally a little suspicious. He nodded, he knew my work he claimed — I’m not sure that was true.

I suggested he should search for information about the Steam gift card scams — that I thought he might find it interesting — and then I left him to carry on.

I walked away feeling sick. He had at least $300 of gift cards in front of him and I doubted it was the first time he’d done this, and even more so that it would be the last time. Scams of this nature, especially with older victims or those who live alone, are often called “pig butchering” scams — a reference to the idea that scammers gain the trust of their victims, like a farmer might be trusted by the pig they’re fattening, and that, in the end, the scammers will fully butcher their victim, extracting everything they possibly can.

I approached library staff to raise my concerns. They were responsive and empathetic — they recognised the man as a regular, and suggested they’d previously warned him that he was likely being scammed when he’d asked for help with some financial transactions on a library computer. Help they’d declined to provide in the circumstances.

But, ultimately, they didn’t know what they could do.

And I didn’t know what could be done either.

I went away from the library feeling quite deflated about what I’d seen — and what I’d been unable to prevent or change.

Was there more I could have done? Should I have been more forceful? Asked if he’d ever spoken to the person he was sending the cards too, or how he’d met them, or what they claimed the cards were for? He didn’t owe me answers to these questions and I doubted he would have provided them if I’d tried.

When I got home I tried to do a little research. Was there a service or organisation who could help? More so was there someone who could actually be at the library within minutes of being asked to come and help?

The police are the obvious option, but I had no confidence that any given beat cop would understand the nature of these scams, although the force in general is very aware of the scam in question. And besides, the victim himself didn’t believe he was a victim so what could they do?

These questions lingered in my head for a few more days, but then I largely forgot about it.

Until, three weeks later to the day, I was back at the library and there he was again. Doing the same thing with the same array of Steam cards spread out in front of him.

This time I didn’t approach — I had nothing better to offer than last time. But I did think of one thing I might try.

Being something of a creature of habit, I was aware that about this time every Tuesday morning the local community constable tended to make his rounds of the area and he’d likely be at the supermarket next door fairly soon. So after checking out this week’s books, my wife and I wandered next door — and I told myself that if I saw the neighbourhood cop I would let him know what was going on, in the hopes that he’d be able to pop next door, see for himself what was going on, and maybe have a chat.

And indeed, as I assessed the tomato options, I saw his marked police car pull into the car park outside. I handed the basket to my wife and headed out to the store’s entrance to intercept him.

What transpired was frustrating.

I explained what I’d seen three weeks earlier, and what was likely still happening next door at this very moment and the officer gave me a fairly blank look.

He wasn’t familiar with the scam, so I explained that too. But still he didn’t seem moved to alter his morning routine.

He suggested that I should tell the man — a stranger to me — to visit the local police station and talk to the desk staff, who would be able to advise him if he was likely being scammed (he was, and he didn’t believe he was, so absolutely wasn’t about to go and ask the police to suggest otherwise). I could talk to the library staff, he suggested, they had his number and could give him a call in future (but he was there now?!)

And, with that, my interaction with the community constable was over as he headed into the supermarket to do his morning stroll through the aisles.

Five minutes later, as we were heading back to the car, we passed the oblivious (or in denial) scam victim as he left the library. I smiled and gave him a little wave. And that was it, a second chance to maybe make a difference was lost.

So now here I am again. At home, wondering if there was more I could have — should have — done?

I wanted to know whether there were resources available that might be helpful in the situation, and was there some advice I could offer to the library staff (and readers) in case they encountered the issue in future?

So I reached out to Netsafe, the non-profit organisation empowered with the role of keeping New Zealanders safe online. I explained my story to Chief Online Safety Officer, Sean Lyons.

Lyons immediately understood my feelings about the experience. “I would imagine there was a great deal of frustration from you as to why they bloody hell that’s allowed to happen,” he accurately intuited, although my personal feelings might call for words stronger than “bloody.”

Netsafe’s online safety role is statutorily defined in the Harmful Digital Communication Act , but that legislation is generally confined to person-to-person online harm and abuse within New Zealand. Fraud isn’t a part of their legislated role, but it is still a big part of what the organisation deals with.

“Nearly half of the reports that we get are scam related, and we definitely help people with scams, but we don’t have any statutory function there because, well, there isn’t one. If both parties were in New Zealand doing that kind of thing, it would clearly be criminal and the police would deal with it,” Lyons explained. But the international nature of online fraud makes the legal aspects complicated.

As for what someone could do, in a circumstance like mine, where they encounter what they believe is someone being taken advantage of by scammers — I asked if there were any formal intervention options.

“Some of the best interventions that we hear about are not particularly formal,” Lyons offered. “They are stories where people have walked into a service station or a bank to engage in one of these things, and the person on the other end of that transaction has said ‘you know what, this doesn’t feel right — are you sure this is right?’”

However the nature of these scams — where victims may have been on the hook and had a slowly developing relationship with their scammer over days, weeks, or even months, before the financial asks are made — means that victims are often unwilling to consider that they may have been taken advantage of.

“If a person has gotten to the point where they’re getting up and heading out somewhere to buy gift cards in order to send money to someone they’ve never met, then they are already probably quite highly emotionally involved,” Lyons observed.

However, as experts in online safety, the Netsafe team is always willing to talk to people who may be concerned about something they’ve encountered online. They offer a telephone help line, email, text message and online chat services.

Netsafe aren’t alone in their interest in this issue. Age Concern, a charity dedicated to advocating in the interests of those over 65 in Aotearoa, does a lot of work in educating their older New Zealanders on the risks posed by online scams.

Chief Executive, Karen Billings-Jensen, was very sympathetic to the story I unfolded for her over the phone. And she reassured me that, yes, it was a really difficult issue. There really is no way to help scam victims who aren’t willing to admit they’re victims.

“We know that banks and other frontline financial institutions work hard to provide information and support to people, who sometimes are resistant,” she told me.

But she also wanted to make it clear that, despite what is often portrayed in news coverage about the issue, older people aren’t more likely to fall victim to scams. CERT NZ (the Computer Emergency Response Team, a part of the government’s National Cyber Security Centre, which is in turn a part of the Government Communications Security Bureau) data shows that the 25-34, 35-44 and 45-54 age groups all had higher representation in scam statistics than the 65+ group.

However, Billings-Jensen conceded that those later in life might have a more difficult time recovering from the financial impact of a significant scam. “When you don’t still have years of income ahead of you, the consequences of a financial scam might be more serious.”

CERT NZ reports that New Zealanders lost more than $6.8 million in the last quarter of 2024 to online fraud. But, of course, those numbers only show the impact of the crimes that have been reported — victims who aren’t aware, or can’t admit, that they’re being scammed won’t be counted in those numbers.

And CERT NZ are the closest thing we have to an official enforcement agency on these matters. Unfortunately, an inquiry about what resources they might have to help in a situation like the one I experienced was met only with a generic statement that could be attributed “to a National Cyber Security Centre spokesperson.”

What they provided was simply boilerplate advice about the tools they make available online, which are certainly useful for those looking to educate themselves proactively, but which don’t really provide any help to those that might encounter other people being victimised.

I offered CERT and the NCSC an opportunity to provide a more detailed response that addressed this type of situation, or even the opportunity to speak directly on the phone, on or off the record about the issue. “The NCSC does not currently have resources to support people intervening in situations where they believe someone else may be subject to a scam,” they eventually offered.

“New Zealand Police may be better placed to provide advice on this scenario,” they concluded. Well in my case they certainly weren’t

Unfortunately this leaves me roughly where I suspected I would be when I started writing: with no better roadmap for a situation like this in the future.

What I did — speaking to the man I met and explaining what I could about the scam I suspected — was about all that I could do in this case. Without a relationship with him I couldn’t really push any further or directly intervene in any way. And the nature of these scams, which are analogous to a traditional confidence trick, makes their victims reluctant to question their circumstances.

However there is one piece of advice I will take back to the library, and offer to any readers who encounter something similar:

The staff of the Netsafe helpline are more than willing to talk to someone in this situation and, while they are possibly no more likely to succeed than any of us, they have expertise, some level of recognisable authority, and are able to answer any and all questions a victim might have about their experience.

I will be recommending to the library staff that if they see him, or anyone else, photographing piles of gift cards in the future, that they give Netsafe a quick call then offer the phone to the person in question. “I was just a little worried about what I saw here… I wonder if you would talk to the internet safety experts at Netsafe to reassure me and yourself that this is above board?”

Additionally Netsafe produces a range of physical brochures and booklets aimed at helping people recognise scams. Ideally I would love to see these, or similar resources, widely distributed. Not just to public workers, such as my local library staff and police, who might encounter scam victims, but also to the retail outlets that sell these gift cards.

It is the sort of direct intervention opportunity that I think CERT should be spearheading.

And to my friend at the library, if you happen to see this article, I would really encourage you to think back on your whole journey with the person on the other end of Messenger, and the stories they’ve told you. Then look into some of the details of common gift card scams.

Just because you’ve already lost money, doesn’t mean you can’t stop. The shame and regret will sting, but denial is just going to make it worse.

-Dylan Reeve.

If you think this piece may help someone else, please share it.

David here again.

I am hearing more and more about these kinds of stories — and so I thought Dylan’s process was really important to share.

I share his utter frustration with the police, who I believe are utterly useless and ill-equipped to deal with the digital world. I honestly don’t think they give a shit.

Different countries have their own version of the cops and Netsafe — and I’m curious if any of you have brushed up against this stuff. Hell, maybe you’ve been scammed yourself. I think about what Age Concern told Dylan — that despite what’s portrayed in news coverage, older people aren’t more likely to fall victim to scams. It’s all of us.

We’re all open to being manipulated by a voice on the other end of the line, or a string of messages on a chat thread. We’re flawed, we’re human, and we can be idiots.

What can stop the butchering is finding gentle ways to intervene with those we love, before it’s too late. With strangers in a library — it may be next to impossible.

David.