The Futility of Punishment

We know hurting people doesn’t actually fix anything. We do it anyway.

Hi,

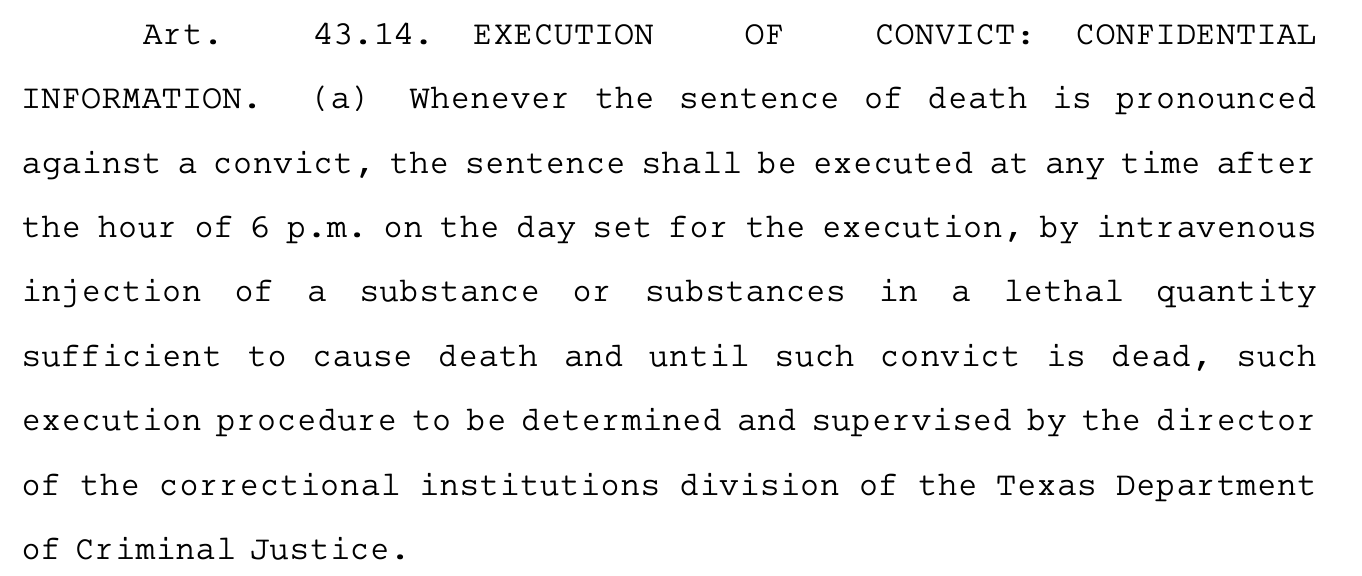

I was in Texas recently and couldn’t stop thinking about how in some parts of America they really like to kill their prisoners.

As a society we tend to agree murder is wrong, but somewhere along the way Texas figured it’s fine if it’s after 6pm and the killing is done via intravenous injection. I know this because I read the State’s Code of Criminal Procedure, specifically chapter 43:

There’s something terrifying about this ultimate form of punishment. There are examples of it being dished out to the wrong people, as documented in films like Paradise Lost and the In The Dark podcast. But even when this punishment is handed down to the “right” people, it still makes my blood curdle.

Since that time in Texas, I’ve been thinking about how we punish people — not just in regards to the death penalty, but incarceration in general.

I’ve spent time Zooming with Bianca Tylek, founder and executive director of Worth Rises, a national advocacy organisation that works to end the financial incentives to lock people in the first place. “We incarcerate a tremendous number of people because we really don’t believe in liberty and freedom in the way that we claim to,” she told me.

“In the United States, we have the highest incarceration rate in the world. We have 4% of the world’s population, and 20% of the world’s prison population. And so in our country we really like to criminalise people: Arrest people and put them in jail, and then often sentence them for excessively long times.”

Robert Craig from Abolish Private Prisons, a non-profit in Arizona, points out there are plenty of financial incentives for America to keep punishing citizens. “They’re expanding into private ankle monitoring, private probation monitoring, all of these other sorts of accessory things to keep expanding their revenue sources,” he told me.

It was with all this buzzing around in my head that I turned to New Zealand, where they’re starting to look at punishment differently. Because there’s a relatively new court there called Te Kōti ō Timatanga Hou — which translates to “The Court of New Beginnings.”

They’re trying something I can only describe as remarkable — and about as far removed from the mindset of America as I can imagine.

Hayden Donnell got permission from the court to attend its proceedings, and see how flawed the concept of “punishment” really is.

David.

Like all of Webworm’s public interest journalism, it’s entirely free, and has zero advertisements. This is make possible thanks to paying subscribers. Only become a paying subscriber if it causes you zero financial hardship. Thank you.

The Futility of Punishment

by Hayden Donnell.

Note: Names have been changed to protect people’s anonymity at the request of the court.

The April sitting of Te Kōti ō Timatanga Hou begins with a small slip-up. Justice Kevin Muir is filling in for the court’s usual judge, Tony Fitzgerald, and he isn’t used to its less formal strictures. He takes the wrong seat, up high where the judges usually peer down upon the gaggle of lawyers, court staff, and defendants before them. This isn’t that kind of court. He descends to the registrars’ desk, where he can speak eye to eye with the people in front of him.

First up is Cora. She’s already pleaded guilty to assault, but this time her appearance is devoted to a debate on whether she should continue with her current café job or enrol in an army skills course in northwest Auckland. It takes her a little while to admit what’s behind her reluctance. “I’m going to be really honest,” she says. “I don’t like getting up early.” Muir encourages her to enrol anyway. “You can do both,” he says. “If you don’t like the course, the job will still be there.” A police officer chimes in with some advice. “Pain is momentary, but glory lasts forever.” The appearance wraps up with Muir telling Cora he’s proud of her progress.

Versions of these exchanges repeat over the next few hours. Lee is making his first appearance in the court. He’s less confident than some of the others; soft-spoken and studiously polite. He has a physical disability and tells Muir he’s worried about being taken advantage of by other people living on the streets.

John is a flurry of activity. He’s been living in a tent on a beach for the last few days but tells Muir not to worry. “I think of it as camping,” he says. He can’t stay long; he’s secured a flat and has to pick up the keys in St John, about a 45 minute journey east.

Te Kōti ō Timatanga Hou translates to The Court of New Beginnings. It’s designed as an empathetic, informal corrective to the punitive, impersonal gears of the regular justice system. All the defendants who appear there are, or have recently been, homeless. They’ve pleaded guilty to offences which carry a community sentence, and are willing to go through a rehabilitative process. If they qualify, they get wraparound support from social agencies, and access to a small corner of the justice system that seems to really care about their wellbeing.

Outside the court, Cora explains how she got here. She was living on the streets outside Auckland University with her then-boyfriend when police came to check on them. There was a confrontation. She ended up being charged with assaulting two officers. Cora readily admits to having an anger problem. But just as with nearly all the people who come through Te Kōti o Timatanga Hou, other issues lurked in the background. A difficult childhood. Substance abuse.

If New Zealand’s new government got its way, Cora would likely be in prison. It’s made ‘tough on crime’ a mantra, and recently brought back three strikes legislation compelling judges to deliver the maximum possible sentence for repeat offenders who commit crimes like assault. The idea is the prospect of a lengthy jail term will make people think twice before offending.

It’s unlikely Cora would have engaged in that kind of calculus, living in a tent on the streets outside uni with a man she says was a bad influence. She’s avoided jail for now, and if the stats are anything to go by, she has a good chance of staying out.

Evaluations have shown Te Kōti o Timatanga Hou reduces reoffending rates by 66%, nights spent in prison by 78%, and hospital admissions by 78%. Cora puts the difference down to being treated with respect. She has two social workers now, and trusts the people involved with the court to want the best for her. “Or if they don’t, they’re doing a good job of faking,” she says. Because they care, she feels motivated to make good on their investment, and take steps not to fall back into old habits. That was never the case in other courts. “They just look at you like ‘here’s another criminal person in the justice system, just doing the same shit and being dumb’. It’s just a fight between you and them,” she says. “Here you’re just getting treated like a human. You’re not just getting looked down on.”

Cora’s story is more the exception than the rule. Punishment is baked into almost every layer of our society. It’s embedded in our stories and pop culture. Half our movies are about a guy getting revenge for the death of his wife, child, or dog by gunning down a small town’s worth of baddies. Politicians compete to propose the most medieval-sounding crackdown on potential lawbreakers. Parents are told if they spare the rod, they’ll spoil the child. The comment sections under crime stories fill up with calls for the return of corporal punishment or public hangings.

Our unmerciful disposition manifests in laws like three strikes, boot camps for young offenders, or Texas governor Greg Abbott loading rivers with circular saws to torture potential illegal immigrants and probably quite a few fish. It inflicts suffering in households, where smacking persists as a form of punishment, or in workplaces where employees are compelled to endure harsh conditions with threats or intimidation. Even making an error on a cooking show might see you wind up having your head placed between two slices of bread and called an idiot sandwich.

At her office in AUT University, law professor Khylee Quince spells out what she sees as the fundamental problem with our reliance on harsh punishment. “It doesn’t work,” she says. She rattles off the stats.

Around 56.5% of New Zealand inmates are reconvicted within two years of leaving jail. Nearly 36% end up back in prison in the same span. A multitude of studies suggest imprisonment can end up perpetuating a cycle of violence. The psychiatrist James Gilligan calls punishment the “most powerful stimulant of violence we’ve discovered yet”. Even the former right-wing New Zealand prime minister Bill English called prisons a “moral and fiscal failure”.

“If imprisoning people or brutally punishing them was going to fix things like crime, violence, and addiction, they would have by now,” says Auckland University lecturer and prisoner advocate Emilie Rākete. “We’ve spent four decades now putting people in prison at a rate unprecedented in this country’s history, and all of these social problems are worse than when we started.”

Awatea Mita spent two years in prison on non-violent drug charges. About 11 months into her sentence, guards came into her cell after the usual 4.30pm lockdown to tell her she needed to go to staff base. She thought she was being put in solitary or high security. But when she got there, she was told her 13-year-old son was missing. That afternoon, on the last day of the school term, he’d been taking turns with his cousins diving off the Whakatāne bridge into the water below. On one jump, he hit his head. Another, he didn’t surface. “The guards were saying ‘hold on to hope’, but there was something inside me, I just knew straight away he had passed.”

Mita was allowed out of jail on compassionate leave for her son’s tangi. An administrative error from an inexperienced guard meant she was only given 12 hours away, rather than three days. She spent 10 minutes with his body on the marae before he was taken away to be buried. Soon after, she was heading to the airport for her flight back to prison. When she arrived at her cell, the guards tried to confiscate the picture of her son she’d collected from her family. The experience did indelible harm. When she got out, she had trouble being in crowds and anxiety making her own decisions. “Prison didn’t do me any good at all,” she says. “It stunted me.”

To Rākete, Mita’s experience is our justice system as intended. She sees prison as “theatre for the rich”, aimed at demonising individuals to distract from systemic issues that cause crime like poverty, addiction, and underfunded public services. She points out that in periods where the working class is strong, New Zealand’s imprisonment rate has generally been low and stable. “The idea that this is how we're meant to make people's lives better just becomes farcical if you ever have any kind of interaction with people who actually have had to go to prison,” she says. “Prisons don't get rid of violence, really, at all. What they do very, very well is concentrate it.”

But prisons are just the sharpest point of a punitive apparatus. Punishment — at least in its retributive, most violent forms — falls down in spheres across society. In parenting, hitting children leads to trauma rather than better behaviour. Just as with prison, it can create a cycle of violence. Most parents who hit their children were themselves smacked growing up. Athletes perform better with positive reinforcement, or sometimes correction, but not punishment. The tech billionaire Steve Ballmer was forced to abandon a ranking system pitting Microsoft workers against each other because it made the company perform worse, and drove employees away.

If behaviour change is the goal, most evidence shows less punitive methods are more effective. A study carried out in a New York state hospital found only 10% of staff sanitised their hands before and after entering a patient’s room, despite signs warning about the medical risks of failing to do so. The stats didn’t change even when cameras were installed next to sanitising stations. Then electronic boards were placed in the hallways which gave instant positive feedback whenever an employee sanitised. Compliance rates rose to 90% within four weeks.

Rewards-based systems may be better than punishment, but they aren’t panacea. Dr Melanie Woodfield, a clinical psychologist who studies parental discipline, says we spend too much time thinking about consequences for behaviour and too little looking at the conditions that drive it. If a bar wants people to buy a drink, it might put out bowls of chips or salted peanuts to make them thirsty. If a parent wants to ward off a meltdown, they make sure their toddler isn’t hungry.

The same principles can be applied more broadly, says Woodfield. Governments looking to reduce youth crime could start by addressing its known antecedents: things like poverty, insecure accommodation, and mental health issues. “You don’t need shame and humiliation to change behaviour,” she says. “If we make sure that people have a place to live, that they’re feeling safe, and they’ve got enough to eat, then parents’ ability to respond to their children is going to be enhanced. And as children grow, they will feel safer and more secure, and they’ll be able to potentially engage with other young people who are feeling safer and more secure.”

Quince says the justice system fails at stopping crime because it doesn’t change peoples’ circumstances. It can’t address inequity or the effects of colonisation. It’s ill-equipped to effectively help people with substance abuse or mental health issues. It’s an ambulance at the bottom of the cliff in a system where the fence at the top is broken. “If you go to any prison, the one thing that almost everyone will have in common, no matter their ethnic background or gender, is poverty. These are people who’ve lived lives of deprivation and restriction of choice.”

Punishment remains so enticing despite all this in the main because it scratches a psychological itch that transcends evidence. New Zealand prime minister Chris Luxon, when challenged to deliver data backing his party’s tough on crime measures, tends to just say they make sense. Mitchell, when furnished with evidence of the effectiveness of a programme to reduce addiction among gang members, simply intones “I don’t agree with that at all” with no further explanation.

Emma Woodward, founder of The Child Psychology Service, sees fear lurking behind our retributive systems. “Punishment is a defence mechanism against our internal feelings of vulnerability,” she says. For people who believe our capitalist systems are just, there’s also an explanatory power in how it hurts the poor. If they’re bad or criminal, then the system that produced their poverty seems less unfair, and the comparatively cushy lives lived by the richest members of society feel less unjustifiable. “We get into this psychological space where we split things into black and white. You do that, you're bad, I do this, I'm good. That makes us feel safe, because we can understand the parameters. We don't have to sit with this stuff in the middle.”

For a long time, Carmel Claridge was one of that system’s more ardent defenders. Back in 2020 she was the 14th ranked candidate for Act heading into the general election. If the party rose a few more percentage points in the final count, she’d likely still be spending her time standing behind its leader David Seymour as he touts spending $1 billion to put more people in prison. Instead she had to find another job, and got one as the convener of Te Kōti o Timatanga Hou.

The role has widened her perspective. She sees what people bring to the court. Abuse has led to addiction or homelessness. Poverty has made them desperate. The government processes they have to navigate to get help are hostile. Once Claridge went down to Work and Income with someone who appeared in the court. They stood in a lengthy line under the watch of security, and were treated with barely disguised contempt when they finally got to the counter. She’d find it hard to navigate as a middle-class person with a home and a stable income. For someone with addiction issues and almost no possessions to their name, it’s all-but impossible.

Te Kōti o Timatanga Hou tries to give choices and chances to people who are otherwise trapped on a treadmill of poverty. In between cases, Judge Muir turns to Webworm for an off-the-cuff interview. He looks around at all the support agencies present in the room and laments the fact that other courts don’t have the same resources and ability to change people’s lives.

Besides the support, Claridge sees Te Kōti o Timatanga Hou’s first, and sometimes most effective intervention, as treating people as human beings with dignity. Just as violence begets violence, kindness can generate kindness, she says. “Many of these people have had no kindness from the moment they were born. No learning how to treat people well. This court gives them that.”

It was kindness that saved Awatea Mita. When she got out of prison, she enrolled in a criminology degree at AUT. But she felt she didn’t fit in at the university as a Māori woman who was older than the other students, and almost dropped out on her first day. A friend reached out to her with encouragement on Tuesday. Then another reached out on Thursday. She found a course that taught te reo Māori and started to reconnect to her culture. Through it all, her mind kept returning to her son, and what he hoped for her when he was alive. “He always wanted me to be happy. When he passed, the thought flashed in my mind to just give up and despair. But I couldn’t do it because he wanted me to be happy. And so I resolved myself that I would educate myself on grief, make sure I don’t fall into the abyss, and then use these experiences to hopefully help other people, and that helps me transform that pain into something meaningful.”

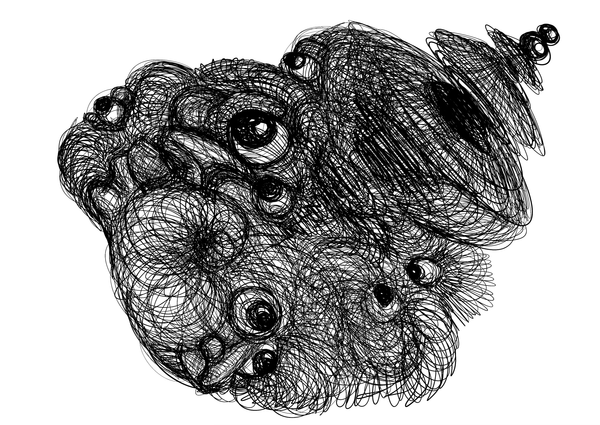

As the session draws to a close at Te Kōti o Timatanga Hou, Paul* sits under a shock of frizzy black hair, speaking in short, sometimes single-word sentences about his efforts to get a copy of his birth certificate. It’s important not just for personal reasons, but practical ones. Government support often isn’t accessible without a form of ID, and poorer people don’t always have any.

Paul is an artist. As he talks, he draws. His notebook is filled with block letters and doodles. He also has a history of painting on walls and roadsides around the city. He tallies the charges. Eighteen counts of graffiti. Three months each. Four-and-a-bit years in jail if they were added up. Instead he’s here, and has recently found a place in a brand new central city social housing complex which has an art room. Muir is excited at the prospect of Paul appearing next time with a new painting to show off to the court. “I’m married to an artist so I know what the artistic process is like,” says the judge. “It’s not easy. I’m really looking forward to seeing that art.”

In the hallway outside the court after his appearance, Paul talks about the possibility of making art, and maybe even putting his work up for sale. “This could be my breakthrough into the art world,” he says. “It feels buzzy.” In his own understated way, he seems overwhelmed at the opportunity. When asked what helped him most getting to this new, more hopeful place, he answers strangely, describing a series of catastrophic events. His mother died. His partner left him. Then he tried to kill himself. It’s almost like he misheard the question. But the incongruousness of the answer keeps nagging, and before the interview ends, we return to it. Why would he describe the worst things that ever happened to him when asked for the best? Paul, a man of so few words, looks up and starts talking with surprising eloquence. “I’ve done the dying and it didn’t work,” he says. “Now I’m going to try living.” He pauses and reconsiders. “Or maybe it did work. Maybe I killed the old dying me, so now this living guy can come out.”

Before he leaves, he picks up a large package wrapped in cardboard that Claridge has given to him. It’s filled with art supplies. As a metaphor it’s almost too on-the-nose. Paul is walking out of the court with a literal blank canvas. But it’s less the object and more the act of giving that’s really important. Thanks to the generosity of others, he has the space to draw something new.

-Hayden Donnell.

You can share this piece if you like — and please do: webworm.co/p/punishment