The Making of a Mental Health Rockstar

Does Mike King’s popularity come with a big dose of impunity?

Hi,

If you’re a New Zealander — you know who Mike King is. He is the face of New Zealand’s battle against mental health problems. He can be loud and brash. He raises, and is entrusted with, a lot of cash. Last year his “I Am Hope” charity reported a revenue of over 7 million dollars.

But something strange has happened along the way.

I often write here on Webworm about powerful men acting with a kind of impunity.

Sometimes this behaviour is exhibited for entirely selfish reasons — but sometimes it can happen even when the person involved thinks they’re helping others.

For the last decade, journalist Jess McAllen has reported on mental health, and Mike King. At times she’s found herself in his firing line.

Over that time she’s gathered together a vast tapestry of Official Information Act responses and interviews related to the mental health advocate, which paint a portrait of a man who moves in the mental health space with a licence to do what he wants.

People bend around him as he does his thing — many simply afraid to criticise or critique because of what might blow back in their face.

But with so much on the line — including money, and lives — I think we need to look closer at Mike King, and how he got to occupy this unique space in New Zealand.

David.

Like all of Webworm’s public interest journalism, it is made possible thanks to paying members, who also keep Webworm 100% ad-free. Thank you.

The Making of a Mental Health Rockstar

by Jess McAllen

Mike King was on the radio station Newstalk ZB in October to talk about an alcohol ban at a fundraiser for suicide prevention. The comedian turned mental health campaigner thought the ban was ridiculous. He told his interviewer, Heather du Plessis-Allan, alcohol could be a vital crutch for people contemplating suicide.

“Alcohol is not a problem for people with mental health issues, it’s actually the solution to our problem,” he said, adding, “I would suggest to you that alcohol has prevented more young people from taking their own lives than it actually takes their own lives.”

Criticism came thick and fast, including from the National government that recently gave King’s charity $24 million in what the auditor-general has called an “unusual and inconsistent” procurement process. Many people pointed out the well-documented link between alcohol and suicide.

Others defended King, arguing he’s been misconstrued or insinuating he’s simply being cancelled for political reasons.

For me, after ten years of covering King as a journalist, the question wasn’t whether the backlash was justified, but why it hadn’t come sooner.

King rose to (New Zealand) fame through his comedy in the 1990s. Many New Zealanders remember him from when he became the frontman for New Zealand Pork, only to later denounce the pork industry, going undercover with activists in 2009 and filming pigs in cramped conditions.

Later that year, while filling in for Martin Crump on a late-night Radio Live show, King talked about his experience with addiction and depression. The talk resonated with a big audience, and the “Nutters Club” radio show was born. He wrote a book, which featured a picture of him grinning in a straitjacket.

I first started talking to King in 2014, when I was fresh off a minor suicide attempt and a few months into my first journalism job at Sunday Star-Times. I was 21, had been waiting for over six months for a psychologist in the public mental health system, and was still reeling from the death of a close friend two years prior. I was impressed by his candor.

When suicide affects you, whether through a loved one dying, or your own attempt or ideation, you feel awfully alone. It feels like no one is talking about it. That isn’t necessarily from malice. Suicidality is hard to understand if you haven’t been there. King broke the silence, confronting the issue head-on in plain language anyone could grasp. He visited schools across the country to front frank, often emotional, talks about suicide.

My admiration started to fade in 2016, when I attended the World Indigenous Suicide Prevention Conference in Rotorua. After staying on a marae with social workers heavily involved in rangatahi suicide prevention, I started to realize King was incredibly controversial, even disliked, by some people at the coalface. They didn’t view him as a rebel shaking up the system. Instead many saw him as turning up to speak to vulnerable young people, convincing them to share their emotions, then leaving others like them with the task of carrying out professional, longer-term care that was really needed.

At one point, King gave up his speaking spot to a group of young people, much to the chagrin of organizers. I started to feel uneasy. That sense solidified further at a conference in 2017, when he called a respected Polynesian Panther activist a “cunt” during their presentation and stormed out, before later returning to apologise.

As my regard for him waned, King was becoming an almost universally admired media staple. He’d spent years as a reliably interesting quote, weighing in on mental health matters. But his star rose to new heights in the leadup to the 2017 general election.

It was a strange time. After ignoring or sidelining the issue for years, New Zealand had whipped itself into a moral frenzy about teenage suicide. Netflix was airing 13 Reasons Why. The New Zealand Herald ran its ‘Break the Silence’ youth suicide series, and the Public Service Association launched the ‘Yes We Care’ 606 shoe campaign.

Though painful emotions were being stirred, many began to see opportunity. At a conference I attended that year, a high-level mental health advocate said the last time there was as much of a push for meaningful change in the sector was in the 1990s, when the public were concerned about police shooting unwell young men. It would be easier this time, she cynically offered, because the cause was more sympathetic: teenage suicide.

King came to dominate the national discussion. On May 15, he resigned from the Ministry of Health’s Suicide Prevention Strategy advisory group and immediately came out swinging in just about every national media outlet. The 2017 draft suicide strategy, which had just gone out for public consultation a month prior, was “deeply flawed”, “pandering to minority groups”, and was a “masterclass in butt covering”. He expressed frustration that the strategy didn’t include a 20% suicide reduction target.

The suicide strategy went down in flames.

King’s profile grew.

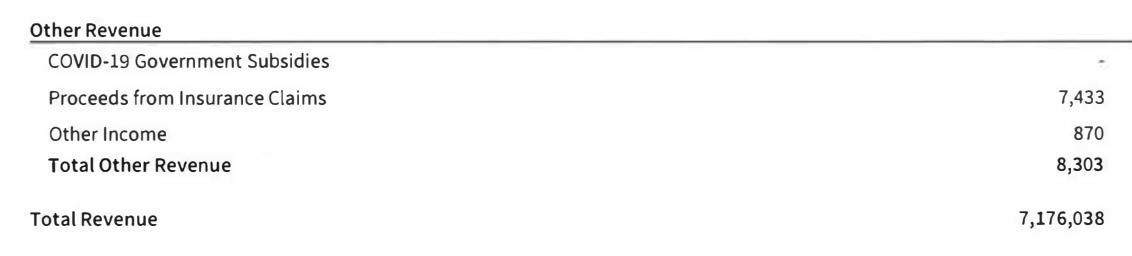

His media ubiquity centred him in our mental health discussion while also attracting investment to his charity. “Key to Life” (formerly known as “The Nutters Club” and now known as “I Am Hope Foundation”) increased its income by 1800% between the year to March 2017, when it declared revenue of $373,386, and the year to March 2024, when it reported revenue of $7,176,038 — most of which came from donations.

For his work, King was awarded New Zealander of the Year in 2019 with judges citing his efforts to shine a “much-needed light on the issues of depression, alcohol and drug abuse and suicide.”

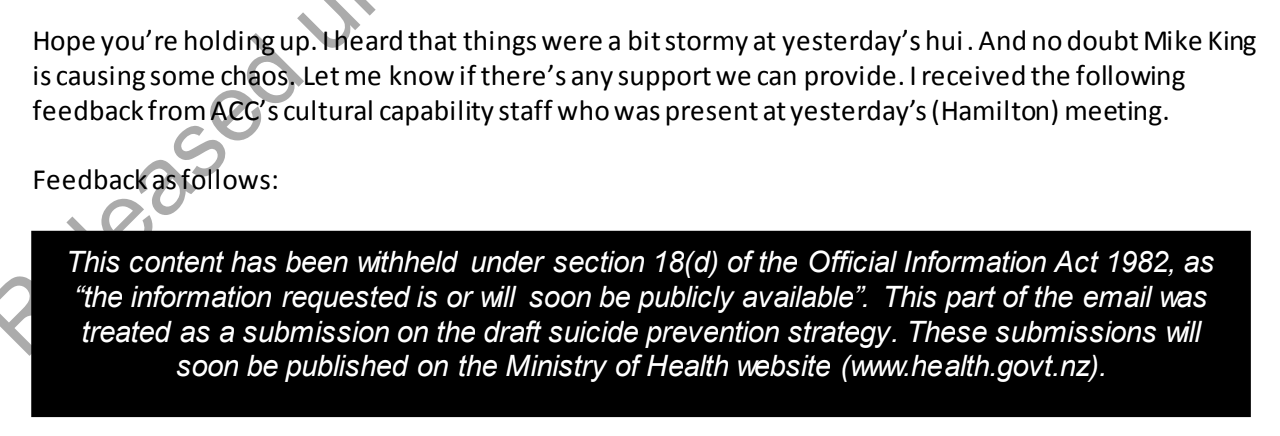

King was a Kiwi hero. But for people in the mental health sector, his prominence had some big downsides. Many times he talked to journalists, he would deliver a concerning quote or misleading statistic. When I requested internal communications about him from the Ministry of Health, I received back dozens of emails, many of which seemed to share my skepticism about King. More often than not, they expressed alarm at things he’d told the media. “Hey - can we please get this corrected? Or rebutted as quickly as possible,” said one email. “No doubt Mike King is causing some chaos,” said another.

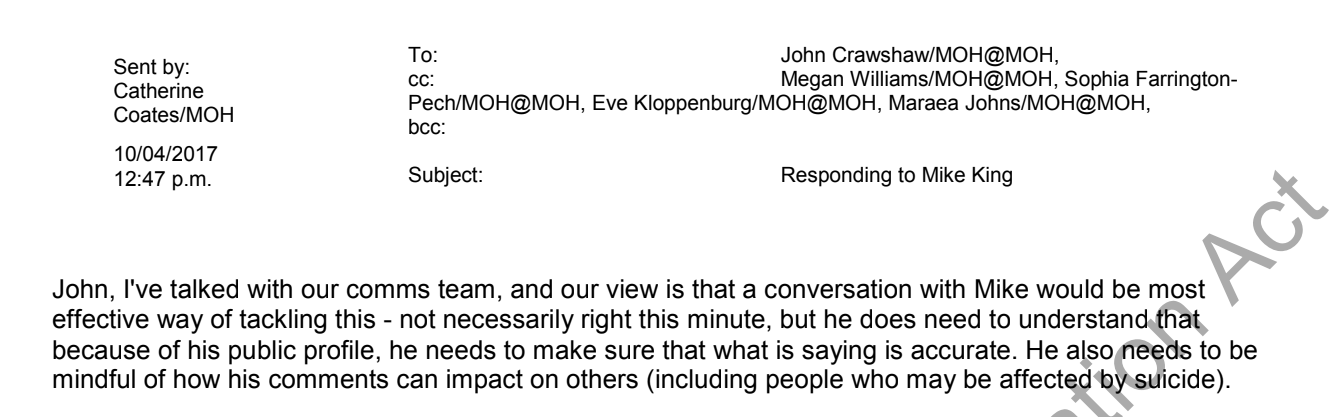

In April 2017, a health ministry advisor sent an email with the subject line “responding to Mike King”. The staffer highlighted the importance of a conversation with King to tackle the misinformation he was putting out, writing “he does need to understand that because of his public profile, he needs to make sure what he is saying is accurate”.

The issue ramped up after King’s resignation from the suicide prevention group. Just the day after he announced his departure, he prompted a fresh batch of headlines after incorrectly claiming on The AM Show that New Zealand’s real suicide figure was double what was reported.

“Autocides aren’t counted, drownings aren’t counted, cliff falls aren’t counted, and anyone who has a trace of drugs or alcohol in their system is not counted as a suicide — even if they leave a note.” The actual number of annual suicides, King said, “would be well over a thousand”.

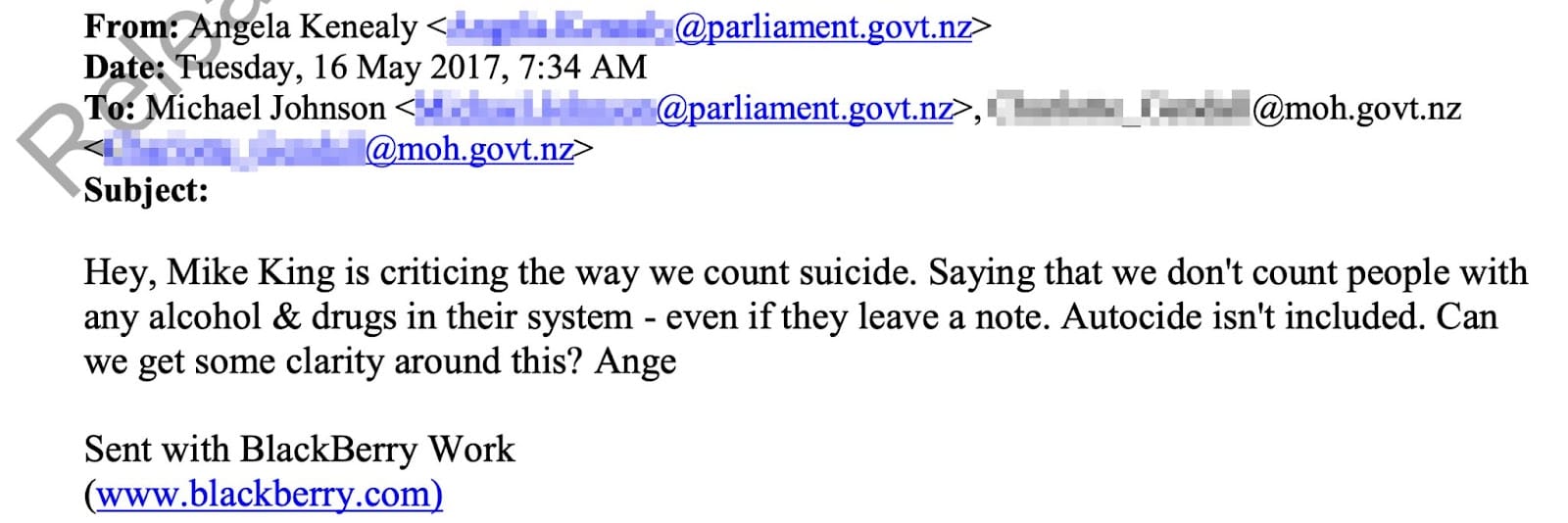

This prompted emails between advisors to the Minister of Health and the Director of Mental Health’s office on how best to address the claims.

I saw first-hand how King’s tendency to shoot from the hip could hurt the people he was trying to help. During that heated 2017 election period, King managed to get a copy of a letter sent to students of Karamū High School in Hastings after a pupil died by suicide. The school’s principal wrote that the suicide was “an irreversible and unacceptable choice… one that, along with her family and friends, we are deeply saddened about”.

King spoke about the letter on RNZ’s Checkpoint and said the principal’s attitude discouraged people from asking for help. It escalated all the way to the Australian website of the tabloid The Daily Mail, where the letter was dubbed “deeply disturbing”.

King later removed the letter from his Facebook at the request of Year 13 students from the school, according to a student at the time who spoke with me a few years ago.

“It made our principal look terrible for what he had written, although in the moment of pain and grief at losing a young life I don’t think he had fully thought it through. By the comment he made of it being unacceptable, I don’t believe it was meant in a bad way, I think he was describing the anguish and trying to stop anything like this happening again.”

The student told me that, despite the media outrage, the school’s staff had been kind and considerate. They gave students a room where they could gather and share memories, and held assemblies where they confronted the issue of suicide head on.

“I think although Mike King is meant to be anti-bullying, in this situation he jumped at the attention and shared something which only hurt a suffering community more. Our principal not only looked tired and lost from the events that occurred but also many parents started to notice his weight loss after this story was produced.”

King’s unpredictable nature and potential volatility was even considered within one of my many Official Information Act responses back in 2018. “The Ministry considers that the main risk associated with the release of the documents is the potential for some damage to its professional relationships, notably its relationship with Mike King,” a Ministry of Health staffer warned then-health minister David Clark’s office.

The briefing said they had taken “particular care” to brief King on the content of the emails written by and about him. Later, King, aware that I had been talking to former acquaintances, texted me: “Respectfully, if you would like I can post on my page that any person who has a beef with me can contact you which will make your job easier?”

This is all to say that King’s assertions on Newstalk ZB didn’t materialise out of thin air. For nearly a decade the Ministry of Health and others have been aware of both King’s temperament and tendency to deliver misleading statements, often on platforms with reach and influence.

But even as health ministry officials emailed back and forth on how to correct King’s latest bit of media misinformation, his star continued to rise, and his organisations were prioritised for funding by both Labour and National governments.

Criticism could charitably be described as muted. Why did he get such an easy ride?

New Zealand’s news organisations have had a big role to play. For a long time, many people didn’t want to talk about suicide. The Ministry of Health — under former health minister Jonathan Coleman at least — was reluctant to even front up on the issue. There were also legal issues. It was only in 2016, when the Coroner’s Act was amended, that media was even legally allowed to report a death as a suspected suicide.

Then King came along. He filled a void. His comments were a tonic: here was someone finally rightfully angry about our high youth suicide rate. His solutions seemed simple and no-nonsense, tailored to appeal to people who hadn’t really grappled much with the issue before. It helped that his sense of humour made it easier for teenagers to let their guard down, while his no-bullshit personality appealed to their staunch fathers.

All that made it easy for journalists to elevate him to vaunted status. They were incurious, perhaps wilfully so, about anyone attempting to puncture King’s image.

But dissenting voices were also hard to come by, partly because King’s scorched earth approach to criticism made people reluctant to come forward. Those sounding a note of caution about his work were painted as fear-mongering and censorious. In September 2019, a group within the mental health advocacy community wrote an open letter raising ethical issues about King’s charity’s 1000 letters research project, which solicited real-life suicide notes. Its signatories included the Mental Health Foundation.

King advertised Key to Life’s ensuing report’s findings on Instagram as “the truth about suicide that Ministry of Health officials didn’t want you to know”. It’s true the ministry’s medical ethics chief had concerns about the project — but she wasn’t alone. King’s comments served to shunt aside the criticism from people with lived experience and expertise in suicide prevention in favour of a narrative about bureaucratic censorship.

Soon after, “Key to Life” posted an open letter to the Mental Health Foundation on Facebook, signed off by its former chair Kyle MacDonald, a psychotherapist, columnist, and former Green Party candidate. MacDonald called on the Interim Mental Health Commission to “review the funding and efficacy of the Mental Health Foundation”.

The foundation hasn’t spoken out much about King or his charity in recent years. One of its former employees says the silence is intentional, and partly motivated by self-preservation. “He had emotions and we had facts and he always won,” they say. “From the moment someone new started at the Mental Health Foundation, we were given the same warning: we don’t support Mike King, but we don’t say anything against him either. He was the reason some of us wanted to do this work. But eventually most of us saw for ourselves the ways his work caused harm, both to us and to the public.”

The former employee now sees the foundation’s reticence as a betrayal of principle. “We ran a national anti-bullying campaign (Pink Shirt Day) with a slogan encouraging New Zealanders to speak up — and in the face of our biggest bully, we were silent”.

Ministry of Health advisors have also been wary of speaking out against King or correcting his statements. One official flagged a potential risk for the ministry while preparing a response to what they saw as misinformation in 2017. “A formal response is likely to result in claims that the Ministry is trying to ‘gag’ conversations about suicide and risks escalating future conversations into an unhelpful space,” they wrote.

King would also use social media to hit back at critics. When he resigned from the suicide prevention advisory group in 2017, a discussion snowballed on Facebook among advocates with lived experience of mental illness. They wondered if this would finally generate change, or if it would have been more effective to stay on the panel. King saw the comments and fired off private messages that were later provided to me.

“I’m not sure you really understand what happened today,” he said. “This wasn’t the actions of a frustrated panelist, looking for publicity. It is part of a very structured strategy… to help services like yours to get the funding you desperately need. Bottomline: I’m happy to sacrifice myself and become untouchable if that means you get the resourcing you need to make a difference in vulnerable New Zealanders’ lives. Would you do the same?”

King used to name people who raised concerns on his Facebook page, often resulting in those people being targeted for vitriolic comments by his fans. When I contacted a suicidologist about this in 2017, they were unwilling to speak to the media for fear it would provoke further attacks.

In an email to Webworm, King says these conflicts are now in the past. Much has changed in the last seven years, both in the mental health and suicide prevention sectors, and with him personally, he says. “While I remain deeply passionate about mental health reform and suicide prevention, I’ve also come to appreciate the value in the work of others. I’m fortunate to have cultivated strong relationships with both the Mental Health Foundation and the Ministry of Health, with whom I am in regular contact. Time, as they say, is a great healer, and I’m focused on strengthening these connections to benefit all New Zealanders.”

King’s statement doesn’t directly address the specifics of his conflicts with others working in suicide prevention, saying there’s little reason to relitigate them years later. “I must admit, I’m unsure of the motivation for revisiting matters from the distant past, and I feel there’s little value in exploring them now, particularly out of context,” he says.

In 2019, Mike King, flanked by prime minister Jacinda Ardern and health minister David Clark, stepped up to a podium to launch the Suicide Prevention Office and endorse the suicide prevention strategy that had been delayed by his dramatic 2017 exit. He’d had a change of heart on the suicide reduction target that had helped precipitate his resignation in the first place. “I’m absolutely fine with there being no target,” he said.

After the launch, Labour ran an advertisement featuring King’s endorsement on Instagram and posted an edited clip on Facebook. In the clip King is featured at the podium saying “so this government did in two years what that last government didn’t do in nine years,” and “the last government paid nine years of lip service and did absolutely nothing”. Even if that government’s own health officials had expressed concerns about some of the things he said, King’s endorsement was still sought-after political gold.

This is not just a story about one man’s unchecked ego. King’s rise reveals serious deficiencies in how we all talk about suicide. It shows that if someone is confident and high-profile enough, we tend to listen when they speak and take them at their word, to the point we might not interject even when they start spreading potentially harmful misinformation about a pernicious social problem. With popularity comes near impunity.

It also tends to come with disproportionate funding. Multiple governments have now spent nearly a decade and millions of dollars supporting King. They’ve found creative ways to fund his charity and shaped strategies in line with his preferences. They’ve invested eagerly in his initiatives, and more reluctantly in fixing the cracks in our public mental health services that created the need for King to speak out in the first place.

That’s done some good. But it’s also come with costs we’ve failed to account for or consider. Just as I had a six-month wait for a psychologist some ten years ago, people with suicide attempts still face a similar, if not longer, wait time in the public system.

In October, on Newstalk ZB, King’s tendency to make dubious assertions caught up with him. He said something that couldn’t be ignored or cast off with a counterattack. But the biggest debate isn’t whether he deserves the criticism he received; it’s why we didn’t start asking tough questions earlier, and what the cost of that silence may be.

-Jess McAllen

David here again. Like all of Webworm’s public interest journalism, it is made possible thanks to paying members, who also keep Webworm 100% ad-free. Thank you.

If you want to get in touch about anything in this story you can reach me in confidence at: davidfarrier@protonmail.com

You can also share this piece if you like: www.webworm.co/p/rockstar — or click this button for more sharing options: