"I Wanted, So Badly, To See His Face"

When we love someone, we close our eyes & see them. Except not everyone can.

Hi,

Four years ago on Webworm, my friend Kate wrote an essay about having aphantasia. In her words, “Aphantasia is the inability to visualise mental images. Most people who have aphantasia are also unable to recall sounds, smell or sensations of touch. That’s me. I can’t do any of it. Never have, never will. Put simply: my imagination is blind.”

I loved what she wrote, and so I recently asked her to reflect on that essay. A few weeks later she got back to me with some thoughts. Kate’s funny, and smart, and I was expecting some jokes and quips. What I ended up doing was having a lil’ cry. Her words were so beautiful and moving, and today I’m sharing them with you.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how our brains all process the world so differently. Last week, I spent half the day with Disa. She’s involved in bird conservation in Denver, and let me get up and close with New Zealand’s endangered kea parrot, and some very friendly flamingos.

I had a blast with Disa, and spent about three hours with her. Later that night, after a live Flightless Bird show we’d put on, a woman came up to me to chat. We talked, and she seemed to know way more about my day than she should have… and, way too late, I realised it was Disa.

I had to explain that I have prosopagnosia, or face blindness, something I wrote about on Webworm ages ago.

My point is — our wobbly wet brains all do things a little differently, and that’s OK. But as Kate will soon explain, it can cause certain complications and complexities, too.

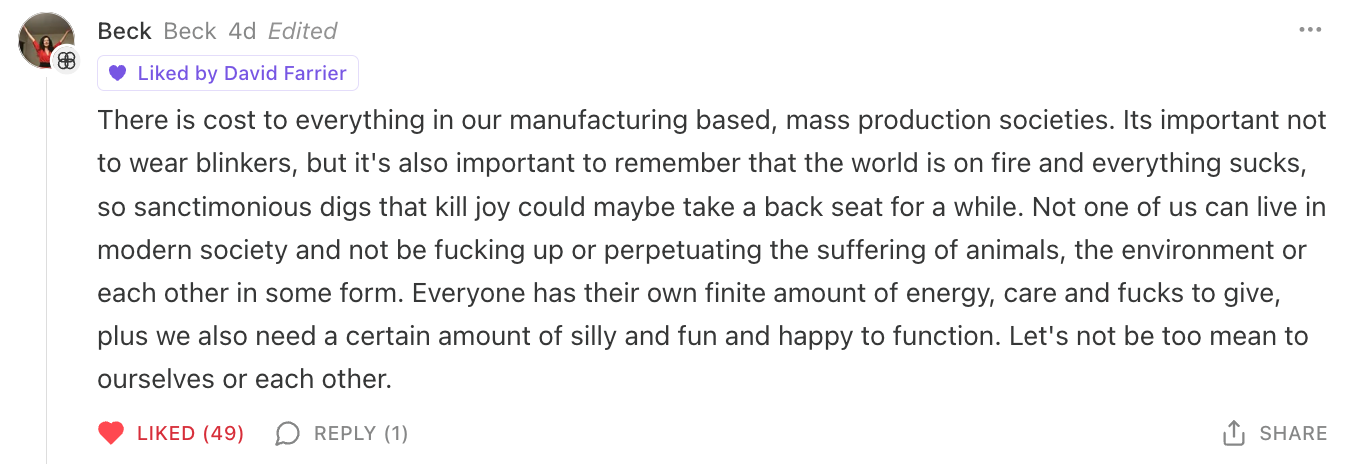

Just quickly, before we get to Kate, I wanted to thank you for all the passionate and considered comments you left under my piece about being a massive milk guzzler.

I’d written the piece after posting a photo of me as a kid drinking a carton of milk, and receiving some quite intense feedback.

That led to me reckoning with my milk drinking, and you left such smart feedback I wanted to say “thanks”. Some of you told me off some more, some didn’t, and plenty mused about the balancing act of living ethically. I value all of your comments, and am endlessly appreciative of the community here.

Finally, if you’re in New York I’m doing a Webworm meetup on Sunday July 13th, and on Monday 14th I’m showing Tickled on the big screen. My buddy John Wilson from HBO’s How To With John Wilson will be there with me doing the Q&A, and I’m giving some tickets away to paying Webworm supporters: all the details are here.

I try to do things like this as a “thanks” for those that support Webworm financially. Paying members make this whole project a reality, so they deserve some fun things imo!

Okay — Kate. Here’s her original essay, followed by a very heartfelt update.

David.

I Accidentally Discovered I Had Aphantasia

by Kate McCarten, originally published March 20, 2021

Just over a year ago — before the apocalypse officially started — I had taken my annual escape from the grim winter in my adopted home of Berlin and returned for a few weeks to my sunny kāinga tupu, Aotearoa New Zealand. I had recently read an article about a woman who doesn’t have a stream of consciousness. As in, she doesn’t think in words. She doesn’t have a voice in her head. It had blown my mind and so I started telling my sister about it. She immediately interrupted me, as sisters are prone to do.

“Oh my god, yeah I know about this—that thing where people can’t visualise stuff, right?”

Wrong. But wait, what are you talking about now?

My sister began explaining that there are some people out there who don’t have a mind's eye; who don’t see pictures in their head when they’re thinking. And that blew her mind. The more we discussed it, the more confused I got. It eventually dawned on both of us why I was so confused: I am one of those people. I don’t have a mind’s eye. I don’t see pictures in my head when I’m thinking. And what’s more, I’d never even realised that anyone could do that.

I’d accidentally discovered I had aphantasia – all thanks to a chance conversation with my sister.

It took me 31 years to discover this very fundamental part of myself.

Aphantasia is the inability to visualise mental images. Most people who have aphantasia are also unable to recall sounds, smell or sensations of touch. That’s me. I can’t do any of it. Never have, never will. Put simply: my imagination is blind.

There are a lot of mind-bending things about aphantasia. But the thing that amazes me most is that it was only officially “discovered” six years ago by a guy called Adam Zeman. Professor Zeman was referred to a patient who’d lost his ability to visualise after a heart operation. Before the patient had heart surgery, he had a vivid, visual imagination just like most people. Afterwards, he couldn’t picture anything.

Professor Zeman began studying this case and after talking to different people, quickly realised that this was not unique to this one patient. If Zeman hadn’t had been referred to a patient who’d had this drastic shift in the way they perceived the world – and hadn’t panicked about it – we’d be none the wiser. And so he coined the term aphantasia. Because the identification of the condition is so new and the research is still so scarce, no one really knows how many people have what I have, but estimates range from 1-3% of the population.

If you want to know if you have aphantasia, this is a good way to find out.

In the year since I found out I have aphantasia, I’ve had many discussions about it with friends. Because most people do have a mind’s eye, the idea that anyone doesn’t seems to be an extremely hard one to grasp. It’s almost impossible for our brains to think about how a different brain works; we are so limited by our own experience. So let me try to break it down for you a bit. Think of the person you love the most in your life. Think of the curves of their face. The colour of their hair. The way they smile. How they look when their face breaks into a laugh. You have a picture of all this in your head as you’re reading this, right? Well, I don’t.

I can’t see what things look like, or hear what things sound like, unless I’m actually seeing them with my eyes or hearing them with my ears. But – and this is the part that is hardest to explain – I still know what things look like. I can still remember things. I still know what my bedroom looks like when I’m not in it. I know what a tree looks like. I know what my mum’s voice sounds like. I can close my eyes right now and I know where the couch is, where the bookshelf is, where the TV is. But I can’t see them. I just know.

A metaphor I read on Reddit once explained it better than I can. Think about it like a computer with the monitor switched off. All the programmes are still running, all the information is still there, you just just can’t see it.

So how had I lived 31 years without realising my brain and imagination doesn’t work like everyone else’s? I’ve had many long and repetitive and exhausting conversations about this, and I still don’t think I’ve ever been able to explain it satisfactorily. I guess the only thing I can say for sure is that I just assumed everyone’s brain thinks in the same way mine does. Don’t you?

But as soon as I realised I had aphantasia, things I didn’t even realise didn’t make sense before suddenly started clicking into place. Why I never remember people. Why I need to write words out on a piece of paper when people ask me how to spell something. Why I never really understood why people were disappointed about the casting for the Harry Potter movies because the actors didn’t match how people pictured the book characters in their head!

And there are a lot of concepts I always vaguely assumed were just hypothetical turns of phrase or story-telling tropes that I now realise are actual real things people’s minds do. Daydreaming. Picturing the audience naked when you’re public speaking. Flashback sequences in movies (memories are actually like that?!). Imagining yourself in your happy place to help calm down. Not being able to get the image of Trump’s mushroom dick and yeti pubes out of your head.

I’ve never had any image in my head. When I’m reading, I can’t see the world the author is writing about. When I’m recalling memories I’m just recalling what I know happened, not what I saw happening.

When I close my eyes, I just see black.

I know it’s hard to comprehend. It’s hard for me to comprehend that most people can see things in their mind. But at least I have a point of reference: I can see things with my eyes, so I can understand what being able to see something is like. The only way I can try to explain it to people without aphantasia is to tell you to imagine black. Not a black room or a black piece of paper. Just black. Just nothingness. And hey, whether or not you can picture that, welcome to my world.

People often ask me if it makes me sad. It’s hard to mourn something you never had, but it does feel like I’m missing out on something. Reading books would probably be a lot better. My sister says reading for her is like watching a movie in her head. That sounds pretty fun.

It would be nice to be able to recall the faces of the people and places I love, especially during the never ending nightmarish hellscape of a Berlin winter during lockdown. And yeah, sometimes if I think about it too much I do feel a bit sad about it. But I think that’s the case with everything, right? And there are some positives to having aphantasia. At least I can’t picture Trump’s toad dick.

-Kate McCarten

David here again. Kate’s story was originally published on Webworm way back in 2021, so I thought I’d ask her for an update, or any reflections on her original piece.

She thought about this for a few weeks, and then sent some words that were beautiful, personal, and painfully honest. And she wanted me to share them.

Her reflections deal on a friend who died by suicide, so please read with care.

An Update From Kate: July 6, 2025:

Way back in the dusty dark ages of 2021, David asked me to write an essay about my discovering I have aphantasia — my inability to visualise mental images (and sounds, and tastes, and smells, and touches). I’d lived over three decades thinking everyone’s brain worked like mine, only to accidentally find out at the tender age of 31 that actually most people can conjure vivid pictures and sounds and movies in their minds. Most people can see their memories; imaginations playing like movies somewhere in the back of their heads. What the fuck?

My brain does not work like that. It never has. And if people a lot smarter than me are to be believed: it never will.

When I learnt about aphantasia – and realised I had it – I found the whole thing mildly disorienting, mostly fascinating, and occasionally inconvenient. I couldn’t visualise anything when I was reading a book. I couldn’t remember faces very well (at least now I had an excuse). I needed to write things down to “see” or remember them. But it was all manageable — even kinda funny, in a Nietzsche, Camus, should-I-kill-myself-or-have-a-cup-of-coffee kinda way.

Then, towards the end of 2022, one of my dearest friends, Sam, died by suicide.

And suddenly, the absence of a mind’s eye stopped being a quirky cognitive footnote and started feeling like a loss all on its own. I wanted – so badly – to see his face; to replay a memory; to conjure the sound of his laugh. But there was nothing. Just the same empty, black void I’d always known. Except now, it felt unbearable.

In the days and weeks after Sam died, I found myself obsessively searching for old photos and videos. Not for nostalgia. For proof. For evidence. Because I couldn’t close my eyes and see him, not even for a fraction of a second. And if I couldn’t see him, couldn’t hear him, couldn’t summon even a flicker of his presence... it felt like he was slipping away too fast. Like he was vanishing from me in a way that wasn’t happening to anyone else.

Everyone grieves differently, I know that. But every time anyone said anything like “I’ll never forget his laugh” or “every time I’m at the beach I can see him surfing”, it felt like a rusty spike to the stomach. Why can you, and not me?

I know those comments were meant to be comforting, or grounding, but they made me feel like I was locked out of something everyone else had access to. Like everyone else was flipping through a photo album and I was staring at a blank page.

There was jealousy. Sharp, shameful, stupid jealousy. It felt ridiculous to be jealous during a time like that — to resent someone for having internal, vivid memories — but there it was. I wasn’t sad that I couldn’t see him in my mind because I’d forgotten. I was sad because I never could in the first place. I never had the chance to forget.

This is the part that’s so hard to explain. I do remember him. Of course I do. I remember how witty and sarcastic he was. I remember how heated he got when he was speaking about something he was passionate about. I remember the way he used humour to alleviate the darkness.

I remember the conversations, the jokes, the shared judgmental eyebrow raises. But it’s knowledge, not image. A list of facts, not a scene playing out in my head.

For people with aphantasia, memory doesn’t mean visuals. It doesn’t mean sound, or movement, or smells, or snapshots. It means facts, feelings, words. And sometimes that feels like a poor substitute — like trying to hold water in your hands while everyone else has a glass.

But what choice do I have? There is no choice. I have to remember Sam in the ways that I can, and make peace with the fact that I can’t remember him in the ways that I wish I could. Maybe memory isn’t really about images at all. Maybe it’s about continuity.

Maybe it’s about how someone’s presence weaves itself into your life so completely that even in their absence, they’re still here — not in the black space behind my eyelids, but in the way I speak, or show up for people, or notice all those little details he would’ve noticed.

I still worry I’ll forget him. That part hasn’t gone away. Maybe that’s why I talk about him so much. Maybe that’s why I write him down. Maybe that’s why when David asked if there was anything I wanted to write as an update to my last essay, my first thought was to write about Sam.

If you do have aphantasia or SDAM and you’ve lost someone, I wanna say this clearly: your grief is not less. Your memories are not less. You are not broken or cold or disconnected just because your brain doesn’t cast a visual slideshow whenever you ask it to.

And if, like me, you sometimes feel like you’re mourning in the dark, try to remember we don’t need pictures in our heads to keep people with us. They stay with us in other ways. In gestures. In jokes. In love.

In us living our lives in the ways they didn’t get to.

-Kate.