20 Years of The Streisand Effect

And how the world's worst people still don't understand what it means.

Hi,

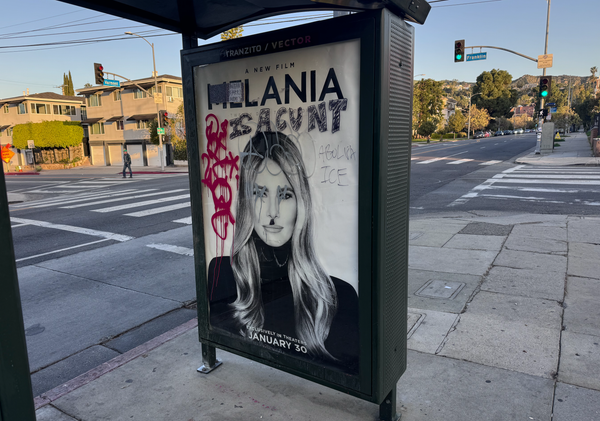

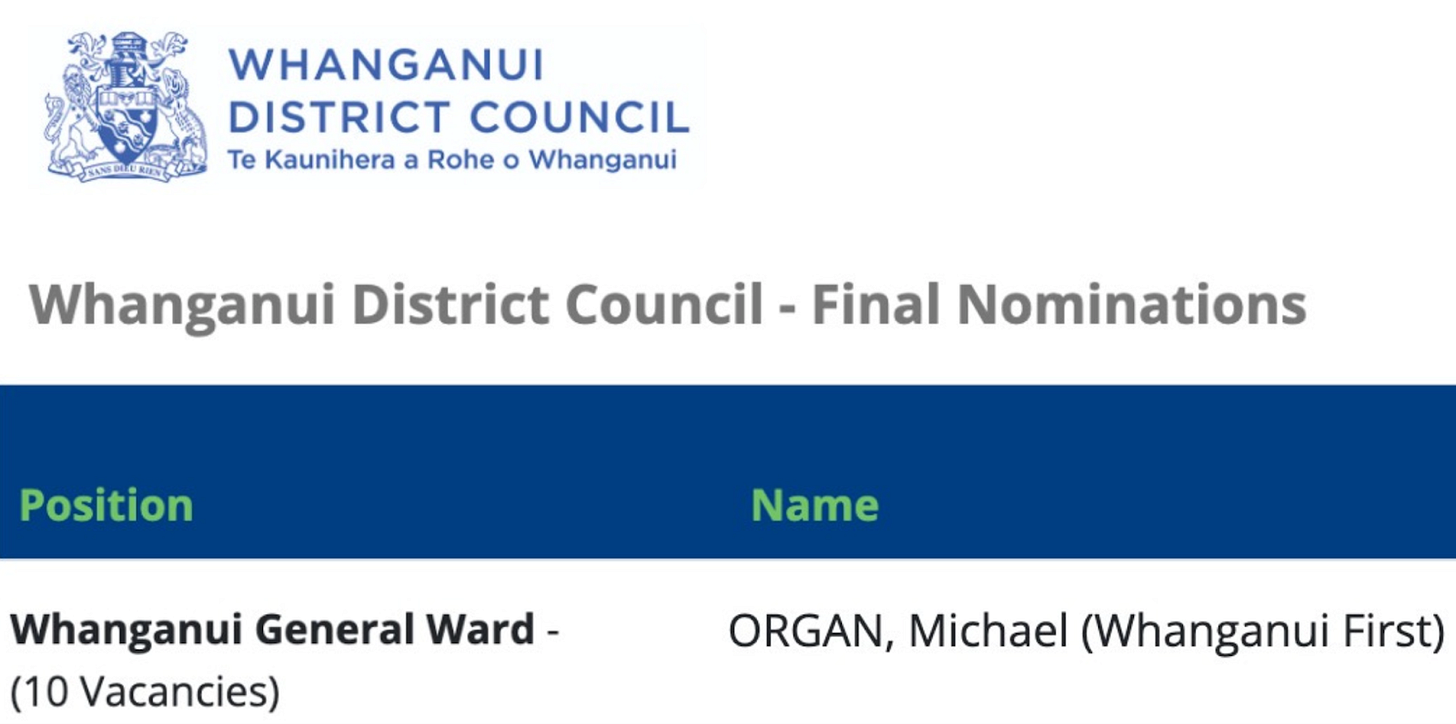

Last week a small shudder went down my spine as I found that Michael Organ, the subject of my 2022 documentary Mister Organ, is attempting to enter New Zealand politics.

If you watched the documentary, you can probably imagine how hectic Organ could get on the campaign trail.

This news got me thinking about how Michael acted when Mister Organ came out: With absolute chaos.

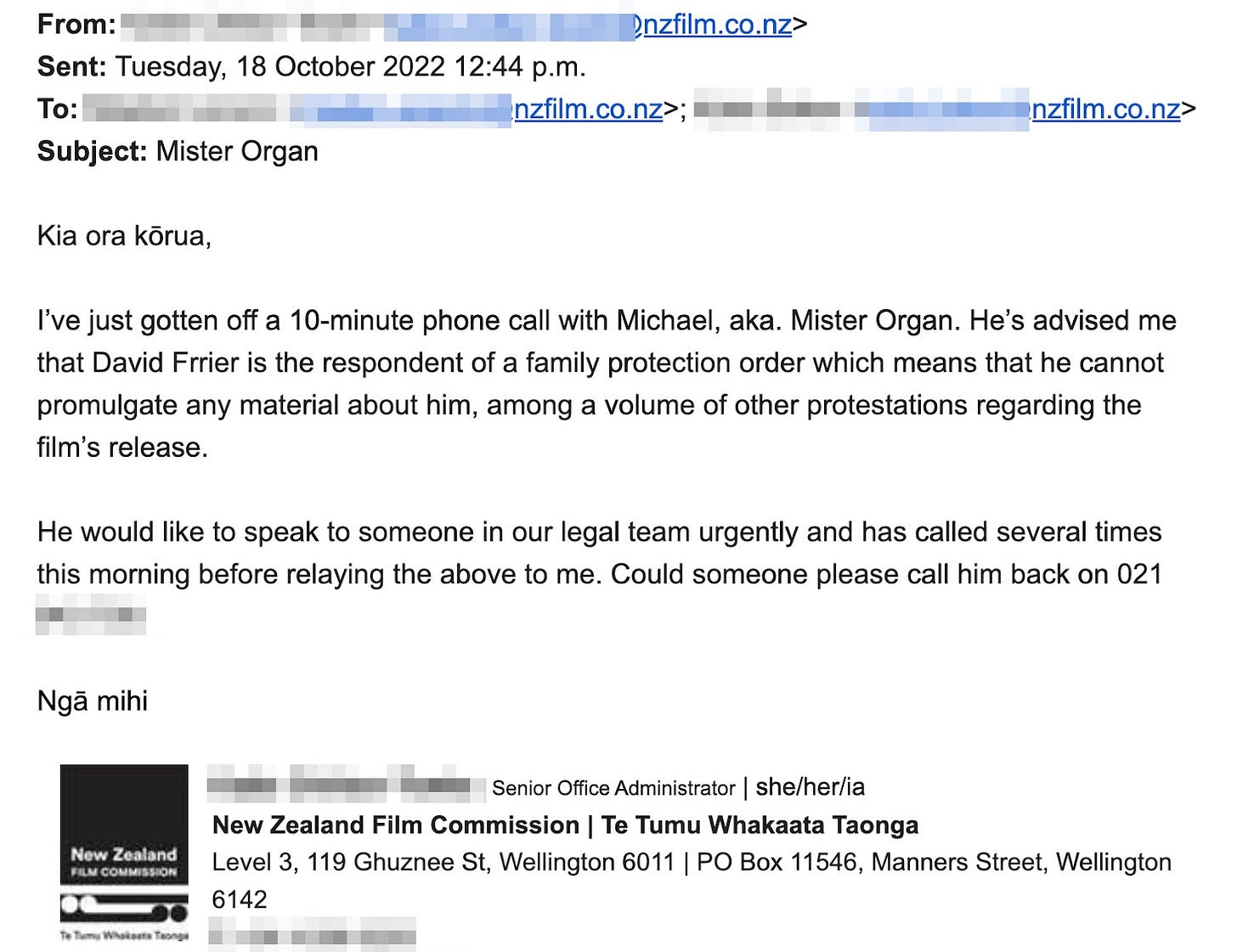

It’s all a bit of a blur, but as the film’s cinema release approached, he took me to court for assault (don’t worry, I didn’t assault anyone, it got thrown out), then used that court case to reach out to the media to try and stop the film. He then started ringing individual cinemas, before contacting the NZ Film Commission (who’d helped fund the documentary):

While this was stressful, it also got my documentary a lot of press in New Zealand, and the film went on to do relatively well.

The subject of previous documentary Tickled, David D’Amato, acted in a similar way. From the second I started making the film it was private investigators outside my house and cease & desists in my letterbox. When the film came out at Sundance, D’Amato sent goons to sit in the audience, creating hype for the film that never would have existed otherwise.

When the film came out, D’Amato turned up to a screening, ate a lot of popcorn, took the microphone, and started issuing legal threats. Shortly after that he sued us. All that got us a spot on ABC’s Nightline, Tickled became a weird sort of indie hit, and HBO greenlit a mini sequel called The Tickle King (free on YouTube).

All of these are perfect, wonderful examples of one of my favourite things: the Streisand Effect.

I feel like the whole planet knows this term, but if not — the “Streisand Effect” describes a very internet-driven phenomenon where an attempt to hide or censor information has the opposite effect.

This year marks 20 years since the term was first invented, so I decided to track down the man — and the story — behind it.

Nearly three decades years ago, Mike Masnick founded a tech blog called Techdirt, which tended to focus on IP, privacy, copyright and legal issues that were arising from this newfangled thing called “the internet”

It was 1997, and the internet was a very different place back then. People used Netscape Navigator and Microsoft Internet Explorer, connecting to the internet via modem which tied up the phone line.

As Techdirt was founded, I was playing videogames like Tomb Raider 2 and GoldenEye, and downloading pirated mp3’s on Napster — one song at a time.

“There was a lot of discussion about what the internet meant, and how big of an impact it was actually going to have. It was a different time — and there were different concerns — but in many ways they were also similar,” Masnick tells me over Zoom.

Mike is still very, very plugged into the internet. Techdirt is still going, and it’s generally agreed upon that Mike inspired Bluesky through a paper he wrote (last year he became a board member at the social media company). But back in the 90s, he noticed that with the rise of the internet came a rise in something else: lawsuits.

“The internet was new, and it allowed people to speak in ways they hadn’t spoken before. There was a sort of rush in the early days of what I would describe as ‘fairly crazy lawsuits’ relating to speech on the internet.”

And that brings us to one very particular lawsuit.

“There was this guy, a fairly successful software entrepreneur, and he also happened to fly helicopters. And he decided that it would be a good project to start flying along the entire west coast of the United States, taking photographs all along the way to document coastal erosion.”

Back in 2003, photographer Kenneth Adelman began his very ambitious “The California Coastal Records Project”. But in amongst 12,000 or so images, Kenneth dared to add one particular photo that contained American singer Barbra Streisand’s seaside house in Malibu, AKA “Image 3,850.”

Streisand and her lawyers came across the photo and sued Kenneth for $50 million. The lawsuit contained five different claims around privacy and publicity rights violations — $10 million in damages for each claim.

Barbra wanted $50 million dollars for one photograph.

“The whole thing seemed like a joke. It seemed like an obvious case of the rich and the powerful sort of abusing the legal system to try and silence someone. There was no basis for the lawsuit. It was just a fabulous story because of the ridiculousness of it.”

Before the lawsuit was filed, the photograph had less than 10 visits, two of which were from Streisand’s lawyers. No-one had seen it because no one cared. It’s not like the photo of Barbra’s house was sitting on a website with the headline “LOOK, THIS IS BARBRA STREISAND’S HOUSE!”. Streisand wasn’t in the photo. You couldn’t see her cat.

It was just a photo of some house on the coastline, along with 12,000 other images of whatever else was on the coastline.

“So basically suddenly everyone saw it. And I thought that was kind of an amusing outcome, and worth calling out. How this attempt to have this content censored would lead to a lot more attention to it. And it felt to me like a particularly internet type of story. It was a quintessential example of how the internet was different from other types of media.”

Kenneth took the photo sometime in 2002. No one gave a shit.

Then — Streisand sued on May 20, 2003.

Mike says she apparently tried to file the lawsuit under seal, but her lawyers messed up, so it was very public.

The Associated Press found out about it and did their story. Other outlets, including Techdirt, followed up.

On June 24th, 2003, Techdirt wrote that the photo of Streisand’s house had become “An Internet Hit” — but the term “Streisand Effect” still hadn’t been coined.

“I think a lot of people assume that I named it that when it happened, but it actually came about from a different story a couple of years later, where I continued to see similar attempts to bully people and use very aggressive lawyering to take down content online.

There was another story that involved a very silly website, urinal.net [editor’s note: Urinal.net still exists]. This was the early internet where people would put up all sorts of silly websites, and this was a website that was just photographs of urinals from around the world.

And so they had gotten a legal threat from one of the locations, some sort of resort where there was a photo of a urinal. And they were like, ‘What do we do about this?’ Because they were just some guys who ran a stupid website. And I was like, ‘Can I write about this?’

And so I wrote about how stupid it was for this resort to threaten them, and jokingly at the very end of the article I said, ‘We should have a name for this sort of thing where a lawyer gets really aggressive and tries to hide something, and instead it leads to more attention drawn to it.

Why don't we just call it the Streisand Effect?’”

Mike Masnick published those two words on January 5th, 2005, almost two years after Streisand had filed her $50 million lawsuit.

“I just made it up on the spot. I included at the end of the article, and linked back to that original article about the photo of her house getting so much extra attention.

It’s really strange, and I had nothing to do with it, which is also weird. I mean, I used it that one time. And then it sort of took on a life of its own through no effort by myself.

I think the first moment where I realised, ‘Oh, this is becoming something larger’, was that Forbes magazine mentioned it. And I was like, ‘Oh, that's like a real publication. Look at that.’

And then NPR’s All Things Considered wanted me to come on with [host] Robert Siegel.”

During that interview, Siegel joked with Mike that he’d made a big mistake, suggesting he should have named it “The Mike Masnick Effect” so people would know it was him who’d invented it.

After those two pieces of press, those two simple words — “Streisand Effect” — went global.

“I think somewhere around 2010 or 2011 it sort of hit that tipping point. It wasn’t something that I consciously tried to spread. It wasn’t like I said, ‘This is my ticket to fame.’ I just named it, and then it sort of took on a life of its own.”

I was really curious about this — how this term, these two words, invented in America — spread around the entire globe. And not only those words, but the meaning of those words. Suddenly we all knew what the Streisand Effect meant.

“That was really when social media was starting. So it was the early days, and you did have Facebook.

And I think really a lot of it came about just because it’s a useful term: When things feel unfair, people want to express themselves about how unfair it is. And so if there’s a simple term that is useful for making that expression get out there, it becomes a very useful thing. So it was sort of a ‘right place at the right time’ sort of thing.”

The other thing I think is really interesting about the Streisand Effect is that it’s a kind of built in PSA. A built-in warning to the rich bullies of the world.

“I would like to think that there’s a sort of public service element to it existing, which is the idea that hopefully it teaches some people not to go crazy legal, when that is sort of an initial instinct.

There was a part of me that always thought it sort of marked a change in how lawyers should respond to a situation. Because I think that pre-internet, the natural inclination of lawyers when a client comes and says, ‘I’m upset about this’, the natural inclination is, ‘We’re gonna go in hard, we’re going to have the most aggressive threatening letter we can possibly come up with. We’re just gonna scare this person into removing that content.’

And the internet enabled this ability for those who were then threatened to talk about it, and for that to become news and draw more attention to it.

And so there is certainly now a class of lawyers who understand the Streisand Effect and recommend to their clients, ‘There might be a better way because this could really backfire on you.’

And I think that’s very much a product of the Streisand Effect. And this idea that, ‘Maybe there’s a nicer way to go about this — and maybe your aggressiveness is gonna do the exact opposite of what you’re hoping’.”

Of course, not everyone listens to that PSA. All around us are constant examples of people not listening — like every time Trump tells people there’s nothing to see in the Epstein Files.

And then there are those who embrace the Streisand Effect because they want to get noticed. A perverse kind of PR.

There was a period of time that I sometimes jokingly refer to as the “Reverse Streisand Effect”, where it felt as though some people were sending legal threats on purpose as a kind of marketing strategy, or acting out that like, ‘Oh I’m gonna be censored!’ so sort of using that to try and get publicity.”

If one were to sum up what the Streisand Effect is all about, I think it’s a story about the internet. About how this new invention really started to change our lives since the late 90s. It strikes me that back then — pre-Streisand Effect — we had such hope for the internet. It was such a magical, amazing place to find information.

Today, perhaps, it feels a lot less shiny.

Maybe.

“I think we’re in an interesting time right now, because the internet has enabled a ton of really good things and a ton of really bad things. And at times it feels like people overweigh one side or the other.

Right now there’s a sentiment out there that it’s all bad and that the world would be better if the internet went away, or all of social media went away.

And I think that’s wrong.

I think we are discounting all of the wonderful things that social media has done. I mean, for a lot of people, it has helped them find community and friends and job opportunities and really, really good things. And the stories of the good things it’s brought are important.

The problems I think have more to do with the nature of who controls social media, what their intentions and interests are, and how they’re twisting the knobs and manipulating it to that interest. And I think that is part of the reason people feel really bad about it.”

Masnick happily admits his bias — he’s on the board of Bluesky afterall — but I find myself agreeing with a lot of what he says. There is this panic around the internet that is worrying, my mind turning to all the current talk of social media bans for kids.

I think it’s very easy to jump to the gut reaction of, ‘Yes, a ban for under 16’s is good: Kids get terrible self esteem issues from social media; there’s bullying, creeps, porn, and horrible behaviour.’

A lot of those points are valid — but unfortunately bans create much bigger, more worrying problems when you zoom out. As Taylor Lorenz wrote over the weekend on The Guardian:

“But while the law and others like it claim to be narrowly focused on pornographic content and material that promotes suicide, self-harm, eating disorders or abusive and hateful behaviour, the subjective nature of the restrictions has led to mass censorship, with the de facto removal of vast swaths of content from the web. Tech companies find it easier and cheaper to simply remove mass amounts of information than have something slip through and be deemed non-compliant.

The Online Safety Act is just the latest in a troubling global trend towards a more censored internet, within which governments and data harvesters have obliterated privacy and everything you do online is logged, tracked and monitored. Australia and Ireland have passed similar age verification measures. Denmark, Greece, Spain, France and Italy have started testing a common age‑verification app, paving the way for potential mandatory EU-wide use.”

It’s also worth looking at those leading the push for bans. In New Zealand, it’s a who’s-who of incredibly rich, white, insufferable privilege — people like Zuru’s Anna Mowbray.

The joy of the internet isn’t that you can create a billion dollar plastic toy empire. The internet is a joy because it’s where marginalised, underprivileged, at-risk people can find each other and create community.

“Yes, repeatedly people forget that,” agrees Masnick.

“Just last week I was at this conference of internet safety professionals. And one of the things that became clear in talking to them was how much damage this idea is that the internet is unsafe for children. That idea is in itself creating safety problems, because we’re not teaching kids how to use it properly.

We’re not teaching kids how to use it in an age-appropriate way. We’re not saying that the internet is perfect for everybody at every age — and you shouldn't let your five-year-old surf randomly, right? — but this idea that it’s all bad and dangerous means that you don’t teach people the good parts of it.

And you don’t teach them how to use it properly and use it well — to find interesting people and interesting communities, and be exposed to different ideas and different ethnicities and all of that kind of stuff.

And so that whole view [of under-16s bans] I think is very dangerous, and I hope that we can move away from that and begin to get back to celebrating the good parts of the internet and making them even better.”

It reminds me a bit of my old school, Bethlehem College — where our sex education class was, “Don’t dare have sex before marriage” We were shown photos of out of control STI’s: warts and ooze and pus galore.

An army of kids was created with a total fear of sex, who found themselves stumbling into the world totally unprepared and blind to a perfectly natural act.

I was curious what Barbra made of all this. I reached out, but didn’t hear back. Luckily for me, she wrote about the Streisand Effect in her book. Sort of.

“She talks about when she first became a star and how the media would make up all sorts of stuff about her. And they would lie about her, and they would say things about who she was dating or whatever — stuff which was completely made up.

And she says in the book that at this time she knew not to respond or to threaten the media — just let the story go because otherwise you turn it into a bigger story than it already is.

She says all that and makes no reference to the Streisand Effect when she does! And implies that she understood it in the 1960’s!

And then later in the book she does talk about the actual Streisand Effect and how it happened, and how unfair she feels that it’s been named after her — without making that connection! I thought that was absolutely hilarious.”

Streisand’s lawsuit got thrown out by the judge, by the way. Absolutely shredded to pieces. She had to pay Kenneth Adelman about $177,000 for his legal costs.

Kenneth’s site of coastal erosion is still up, including his photo of Barbra Streisand’s Malibu home. If you want to be reminded of what the internet looked like in 2002, please visit his site: californiacoastline.org.

This year makes it 20 years since Mike termed the “Streisand Effect” — a time in internet history when we were reminded that the little guy had a chance to push back against the rich and powerful.

And maybe today in 2025 it’s nice to be reminded of that.

David.

PS: There are 28 uses of the word “Streisand” in this piece. Make that 29. That’s way too many.