Unfortunately, Being a Hero is Mostly Illegal

How the fantasy of having agency is just that: A fantasy.

Hi,

Today is a pretty heavy, weighty Webworm — so maybe get yourself a cup of tea or coffee before you settle in. It’s about, you know, the end of the world and stuff.

Before we get to that, I’d like to say I thoroughly enjoyed the notes you left under my “I Found A Note In A Tree” story.

Rowan’s words in particular hit me:

“Sometimes the woods are the only place where I feel like I don't have to mask my autistic self for the benefit of others, messages like ‘Smile’ would definitely be jarring in the place I go expressly to avoid that sentiment.

I love that people want to be kind and inspire happiness and joy in others but I am definitely one of the curmudgeons that finds this particular version grating.”

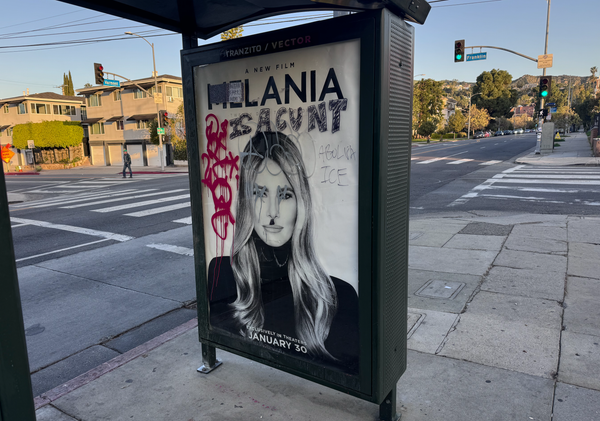

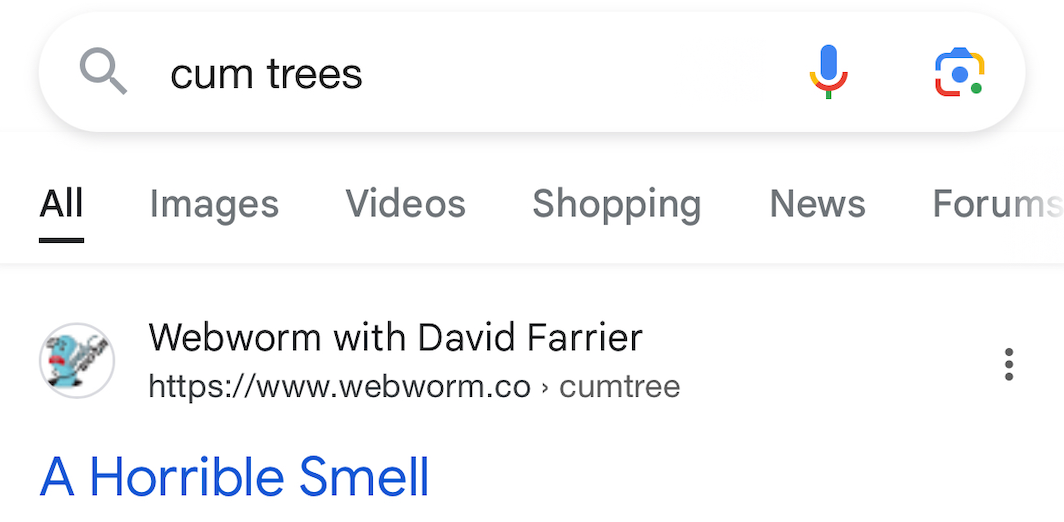

In happier news, I’m proud to announce that this Webworm deep dive is now the top result for anyone googling “Cum Trees”. We’ve made it!

As if things couldn’t get better than that, I also got to hang out with David Chen — someone whose podcast (The Filmcast) I’ve been listening to for about 15 years now. He also writes an excellent pop-culture newsletter called Decoding Everything. We are mostly online friends, which makes it a real thrill when we get to hang out IRL. Look at the happy couple!

Now — onto the heavy stuff. Really.

A little over three years ago, Webworm semi-regular Josh Drummond wrote a piece called “Imprisoned In a System That Won’t Let Us Act”.

It was about how we are being denied what he called “climate agency”; about how we are all prevented — on a vast, horrifying scale — from doing anything meaningful about the global climate change emergency that threatens the biosphere and, well, all human civilisation.

Josh lay out his theory that this denial of climate agency — and the way we are being forced to act in ways we know are insane — is slowly driving us mad.

Today, Josh still feels the same — only more so.

And he wanted to try and understand why.

Unfortunately, he may have figured some of it out.

David.

The Fantasy of Having Agency

by Joshua Drummond

The hills frame the rising sun. As it paints the clouds with pastel shades of orange and red and pink, you stand on the precipice of a great cliff. A wide green land lies before you. Yet it is bespoiled. A blight rises above the castle, and evildoers terrorise as they march. Your hand goes to the hilt of your sword.

You run.

You leap.

You fly.

Most days, before starting work, I need to quite intentionally shake off a Sadness so deep and profound it warrants a capital letter.

I’m not depressed, not in the medical sense. And I have a wonderful family and a nice home and a good life. I feel like an inherently cheerful person who would be quite happy-go-lucky were it not for:

- the genocide

- repression of basic human rights

- the constant legislative attacks on some of society’s most vulnerable and marginalised people

- the march of imperialism

- the rising tide of fascism

- a political system that seems to be an eternal split between two hateful choices: bad, and worse

- responding to inflation (caused mostly by oil pricing and corporate profiteering) by deliberately engineering recessions, arbitrarily raising unemployment to keep wages low

- the world’s refusal to countenance any alternative to an economic system that is engineering an inescapable global emergency which (science says) if not stopped will devastate our only home and destroy any hope of a decent future for our children.

I think any of those are fairly normal things to be Sad about.

And yet, there are cynics among us. “Oh Josh,” you, an intellectual – probably an economist – reassure me. “There have long been bad things in the world! War will always be with us. Now, sit down, have a drink, and forget about all those dead Palestinian children.”

But that’s just it. I’ve made every effort to just shake it all off.

I do what everyone else does. I escape into unreality.

I read books. I watch movies. I play videogames.

The reason I am still Sad is that, for my whole life, the juggernauts of pop culture told me a bewitching, powerful lie.

Practically all the most popular media and mega-franchises, across movies, books, TV shows and videogames, contain at their core the ultimate desire. One that I think may be poisoning our minds and destroying the possibility of climate action in ways both obvious and subtle.

We are being sold a fantasy of agency.

A young person – usually male, but thanks to Big Woke, now sometimes female – finds out they have a destiny. Their task is to destroy a great evil. Despite hardships and complications, they achieve their goal. Sometimes they sacrifice themselves in the process, but usually they survive the quest, often to retire quietly, bearing the scars of their great journey.

Anyone who’s dabbled in media studies or just TV Tropes will recognise this structure: it is the monomyth, as articulated by Joseph Campbell in The Hero With A Thousand Faces.

As befits a myth, the monomyth is not true. But its influence in media is impossible to overstate. When it comes to popular culture, it’s not just a structure, it’s the structure. Nearly every juggernaut franchise, be it book, movie or videogame, hews to it.

In Star Wars, the chosen one destroys a great evil

In Harry Potter, the chosen one destroys a great evil.

In the The Legend of Zelda games, the chosen one… you get the idea.

The structure is so ubiquitous and well-known I wonder if it’s made us miss some of what's going on. It’s not necessarily that the monomyth itself is what appeals – indeed, we frequently see criticism of movies that adhere to the same tired formula even as audiences flock to see them – but the fantasy of freedom that lies at the monomyth’s heart.

The appeal of agency explains the success of media that has nothing to do with the monomyth. For every Legend of Zelda where you play as the world’s saviour, there’s an Animal Crossing or a Sims or a Stardew Valley; “cosy” games where you get to act out the increasingly rare, highly agential activities like having time for meaningful projects or owning your own home.

It’s present in other media as well. The children in the Enid Blyton books I devoured as a kid have all the agency in the world; they roam the British countryside at will during their endless school holidays, solving crimes and putting the world to rights. Today, as my son watches Paw Patrol, I think the talking dogs might be the least unrealistic part. Far greater is the fantasy that adults, let alone children, have any agency at all.

Over and over again, from childhood onwards, we are sold the vision of a world where radical choices that make a positive impact on the world — in other words, heroism — is an option. Consequently, we all want to be heroes.

Unfortunately, being a hero is mostly illegal.

You sit bestride a mighty steed. You were able to name it, so its name is Horsey von Horseface. Its name makes it no less mighty.

Atop a hill, you watch as the sun sinks behind a distant, muttering storm. The wind ruffles the sheepskin fringes of your greatcoat and sighs through the trees, followed by a light scatter of raindrops.

On the plain before you, little dapples of light spring from the homesteads and campfires of fellow travellers. One of them belongs to the gang who kidnapped your friends. They do not know it yet, but they will soon play host to rough justice.

Unconsciously, your hand goes to the hilt of your gun. The other gently tugs the reins of your steed. Horsey von Horseface whickers, eager for the battle to come.

You ride into the gathering night.

You could still try heroism. But it probably wouldn’t go well. Any attempt to emulate the heroes of popular media franchises would almost certainly see you in jail, or shot. The unrealism of heroics might be more tolerable were we not beset by overt Saurons, Palpatines, Voldemorts and Lex Luthors; evil emperors waging vicious war on defenceless civilian populations and mad billionaires intent on colonising Mars. We have villainy to spare, on a scale that screenwriters would consider cartoonish.

Meanwhile (I am correctly assuming no-one reading this is a billionaire) our actions never seem to have mattered less. In fact, for most people, they seem increasingly restricted to two options: to consume, or not to consume. Is your university investing in oil companies? Write them a polite letter asking them to stop. Is your coffee company sponsoring genocide? Don’t buy Starbucks.

I’m not mocking boycotts and divestment campaigns, as they have real effects - but they seem a poor substitute for more direct justice, which world leaders have decided cannot be allowed. And even this paltry power, to use what little agency we have left to decide what to buy, is often threatened or outright outlawed.

Attempts to be more heroic, even in the mildest ways imaginable, are meeting with more and more repression. All over the purportedly democratic world, non-violent protest is being violently outlawed.

In the UK, both Labour and the recently-ousted Conservatives are aligned in their furious opposition to people putting paint on the glass protecting paintings, or chalk dust on rocks, to highlight the very real danger of climate change; Attempts by (again, non-violent) protestors to highlight the ways in which humanity is unwisely challenging the laws of physics are increasingly being met with draconian jail sentences, after the traditional police beating.

The only actions permitted, according to fossil fuel’s political enablers, are to sign petitions, or vote — either for the Bad Party or the Worse Party. On special occasions, we may walk down a road with a few like-minded people at an appointed time, as long as we inconvenience no-one.

With protest neutered, we are taught to mock and deride those earnest enough to persist. Silly schoolchildren, striking for their futures! Don’t they know that all we need to do is create carbon credits, and let the market work its magic? Scolded sternly by our economic betters, we are told to take individual action, and consume our way to a stable climate.

And there is always the stultifying, inert, impossible fantasy of heroic agency to distract us from the real horrors that beset us.

Sad, isn’t it? Now, now. Don’t be upset! Here is a video game in which you’re the hero and your actions matter. Agency can be yours for just $110.

(Or $150 for the premium edition. It comes with a unique set of armour for your horse.)

You stand on the shores of a great still lake, the moon rising swiftly above the scudding silver clouds. The lake reflects, and so do you.

You wish none of this had happened, but that is not for you to decide. All that you get to decide is what to do with the time that is given to you. There’s a Dark Lord that needs defeating. If you don’t find a way, no-one will.

A boat glides out of the shadows, and ripples spread out ahead of it, marrying your reflection.

Your hand goes to the backpack sitting by your side, which contains your weapons. Bottles, rags, petrol, a lighter.

Your companions help you into the boat, and you take an oar. Your destiny awaits.

Getting the world hooked on time-consuming heroic fantasies that are impossible to live out in real life isn’t some conspiracy by the fossil fuel industry. But it may as well be, because we now have a broken society that has been given faulty instructions for how to fix itself.

There are two problems. One is that when heroism is called for, few are willing or able to make the sacrifices that heroism demands. And there’s a great danger that those who do see themselves akin to the heroes of pop-culture and are willing to sacrifice others often act in the most villainous ways possible.

I don’t have to reach to find examples, and neither do you.

The second problem is that while villains might be real, heroes mostly aren’t — at least not the ones we’re presented by mainstream entertainment. I argue that, while heroism has never been more necessary, real heroism is so far removed from popular motifs that being heroic will require some concentrated unlearning.

To my mind heroism is activism, it is journalism, it is mutual aid; it seeks justice and avoids violence; it recognises that individual action alone cannot win the day, but that collective actions are made of many individual ones.

The reason superheroes are given superpowers in movies is because it’s a screenwriting shorthand for people power, of investing the strength of tens or hundreds of people in one person. When struggles against injustice were won in the past, it happened because of mass movements. (Of course movements have talented figureheads and leaders who are later held up as heroes, but plenty of that is post-hoc justification.)

Where our popular conception of heroism is correct, it is that it is anti-hegemonic, pro-justice, pro-diversity, anti-Empire. The problem remains that, when held up against mass-media templates, real heroism is also fallible, bureaucratic, boring. It is organisation and committees and funding drives and arguments over meeting minutes rather than pulse-pounding action.

If we rediscover a crucial fact – that true heroism lies in the many small individual actions that add up to a collective movement – then maybe we’ll still be able to take down the very real villains that are destroying the Earth.

If it works, there might still be a civilisation around one day that might make a heroic movie about it.

-Joshua Drummond

David here again.

I grew up on a diet of action films where heroes saved the masses, usually leaving a trail of bloodied bodies behind them.

The Hollywood fantasy of being a hero — Stallone, Seagal, Schwarzenegger — is deeply embedded in my brain, and so I really felt Josh’s piece in my bones. But try doing a Neo or John Wick on the baddies of this world… and it’s not gonna work out so well for you.

I also have How To Blow Up a Pipeline running through my head. I rewatched it after editing Josh’s piece. It’s an amazing film — edge of your seat, terrifying stuff that makes you want to scream.

It’s based on Andreas Malm’s non-fiction book of the same name, in which Malm argues blowing shit up is an incredibly valid form of climate activism.

I agree we need to gather into some kind of collective movement, but fuck I feel discouraged. I look around and see the sheer gravitational pull someone like Elon Musk exerts over so many, and I don’t even know where to begin.

This system might as well be the Death Star, and nothing in Star Wars taught us anything real about defeating it — just lightsabers, wookies and mystical green men.

David.

PS — Josh linked to it in his piece, and I just mentioned it in passing — but Elon’s Mars dreams really are just horseshit. This piece is a great, hilarious, frustrating read:

“This doofus’s birdbrained space-colony takes are important to know; that alone is a very awful and embarrassing true thing to say about the state of things. Capitalist society permits such profound inequalities of wealth and power, and the U.S. has allowed its public sector to lapse into such abysmal decay, that a guy like Musk exerts a terrible gravity on the world around him: What he is interested in seeing done, some number of other people will work on doing, because that work pays better than nearly all others. Whatever pit he wants to throw his money into, some appalling volume of the world's resources and human labors will follow it down.”