How the Far Right Weaponised the Grooming Gangs Story

How racist agitator Tommy Robinson found support with the world’s richest men.

Note: This Webworm discusses sexual assault and rape. Please read with care.

Hi,

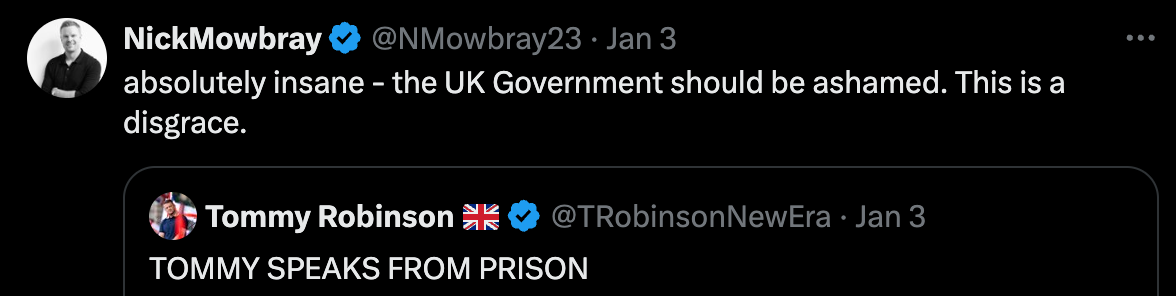

A few weeks ago I reported on how one of New Zealand’s richest men, Nick Mowbray (he and his brother own Zuru and are worth an estimated $20 billion), had taken to sharing posts by a British man called Tommy Robinson.

Mowbray wasn’t the only rich man doing this — Elon Musk spent weeks on X boosting the views of Tommy Robinson.

To be clear, Robinson isn’t a little bit racist — he’s really, really racist. He’s one of the UK’s biggest far right campaigners and is vehemently anti-Islam.

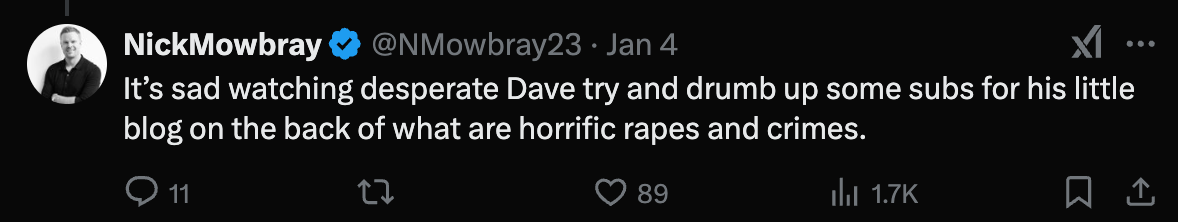

What may have also puzzled you was what Nick Mowbray tweeted at me (AKA Desperate Dave):

“On the back of what are horrific rapes and crimes.”

What was the New Zealand billionaire talking about?

What rapes and crimes?

To unpack this particular wormhole, I am handing today’s newsletter over to Dr. Annie Kelly.

Kelly is a journalist and researcher based in the UK, specialising in anti-feminist and far-right digital cultures. She is also the UK correspondent for one of my favourite podcasts, QAnon Anonymous — and I’ve been wanting her to write for Webworm for ages.

I’m very happy to have her here, making sense of why some of the world’s richest men are boosting the views of one Tommy Robinson.

David.

Like all of Webworm’s public interest journalism, this edition if free to share using this link: https://www.webworm.co/p/tommyrobinson. This is made possible thanks to Webworm’s generous paying subscribers.

How Racist Agitator Tommy Robinson Found Support with the World’s Richest Men

How the far right have taken a story of real institutional failings and twisted it into a weapon against immigrants, the left, and many of the victims themselves.

Dr. Annie Kelly

When someone next snidely reminds you that social media isn’t real life, it’s worth bearing this story in mind.

In the course of a little over a week, discussion of the UK grooming gangs scandal has travelled from an exchange by anonymous right-wing accounts on X, to the leader of the Opposition calling for a new inquiry in the House of Commons.

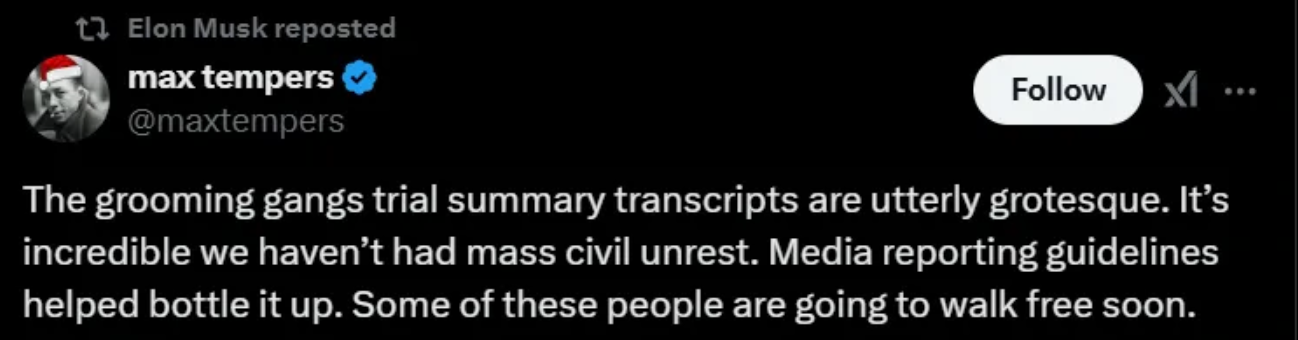

On the 30th December, 2024, the user “@maxtempers” on X quoted a smaller account, “@wolfofclapham”, saying “People should have hung for Rotherham”. They added a screenshot of the sentencing remarks (not actually from Rotherham, but a similar child sexual exploitation case involving a gang in Oxford), along with this commentary:

“The grooming gangs trial summary transcripts are utterly grotesque. It’s incredible we haven’t had mass civil unrest. Media reporting guidelines helped bottle it up. Some of these people are going to walk free soon.”

As of the time of writing, both of these accounts had under 15,000 followers - and they almost certainly had far less at the time. The child exploitation rings that they referenced, in Rotherham and Oxford, were convicted around 10 years ago.

The users had brought these cases up to add their voices to a small squabble erupting on the online British right over a piece by Fraser Nelson, then-columnist for the right-wing Daily Telegraph, in which he praised multiculturalism in the UK and what he called the British “integration miracle”.

For the British far right, “Rotherham” or “grooming gangs” are all that is needed to counter this particular belief. The details of these cases are so harrowing, they argue, that only the most ideologically committed could look at the facts and still believe in British multiculturalism.

This back-and-forth is a conversation that the right in this country are pretty much constantly having with themselves. What made this turn into a political firestorm, was the fact that the richest man in the world, as part of his crusade on behalf of the jailed far-right activist Tommy Robinson, saw the exchange and decided to amplify it to an international audience of millions.

Suddenly people all over the world were being introduced to the Rotherham grooming gang story, or other related cases for the first time.

I’ve seen a lot of confusion from non-Brits on this topic, with some claiming Tommy Robinson is in prison for trying to bring the truth about Rotherham to light (he isn’t), or that the case was a subject to a media cover-up (it was one of the biggest national news stories of the 2010s, there have been several primetime documentaries and a BBC drama).

On the other hand, it’s important not to get so negatively polarised against bad-faith actors that you end up talking nonsense yourself. “Grooming gangs”, or more precisely, gangs which engage in on-street child sexual exploitation, are a real phenomenon. And for decades in many of this country’s most deprived areas, the state’s response to their activities was negligent at best, complicit at worst.

Even now, the recommendations of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, which investigated institutional responses to the issue in the wake of the scandal, has yet to have had any of its 20 recommendations implemented. The victims were failed by the state that should have protected them, and they continue to be failed today. If this was the only claim Tommy Robinson, Elon Musk, Nick Mowbray, or Nigel Farage were making, I’d find myself in the unusual position of agreeing with them.

But it isn’t. As is the far right’s talent, they’ve taken a story of real institutional failings for which there is real public anger and twisted it into a weapon against immigrants, the left, and ultimately, many of the victims themselves.

It would take an entire book to detail the full history of the “grooming gangs” story in this country. We don’t have that kind of space here, so this will be, as briefly as possible, an explanation of “grooming gangs”, Rotherham, and what the far right gets wrong about both.

“Grooming gangs” became national news in the United Kingdom in about 2011 after a series of high-profile stories ran in The Times. These stories drew attention to several court cases across Northern England and the Midlands in which two or more adult men participated in an exploitation scheme where they befriended underage girls, some as young as 12, before raping and brutalising them. Many of the girls had been physically imprisoned, sold to other men for sex, and trafficked to other gangs in nearby towns and cities.

This form of abuse is sadly a very old story. The slums of Victorian London will have been filled with countless women and children who shared a similar origin of desperate poverty and neglect, before being exploited in the most violent way by someone they thought they could trust.

Nonetheless, the sheer scale of the problem was a shocking one. And it continued to grow as further cases emerged, mostly in poorer post-industrial northern towns like Huddersfield, Rochdale and Oldham, but eventually extending as far south as Oxford and Bristol.

There was also a strong racial element to the cases that differentiated them from the “usual” stories of child abuse in people’s minds. A great majority of the perpetrators were from British-Asian Muslim backgrounds, while their victims largely weren’t. As The Times noted in their very first article which first broke the story:

“[In the 17 original cases covered] Three of the 56 [men who were convicted] were white, 53 were Asian. Of those, 50 were Muslim and a majority were members of the British Pakistani community.”

As further cases were uncovered and more victims came forward, something particularly disturbing was revealed. Local authorities, including the police, care home staff and social services, had been made aware at several points over the years as to what was happening, but didn’t act. Victims were ignored, brushed off if they attempted to report their abuse, and in some cases actually arrested for defending themselves.

This happened in too many localities, but the sheer scale of the abuse in one south Yorkshire market town, where a local inquiry found that at least 1,400 children had been abused, meant that “Rotherham” became a national byword for the scandal at large.

The Times, whose chief investigative reporter Andrew Norfolk led the charge on the early coverage of the scandal, was clear as to what had facilitated this “culture of silence” - political correctness. They quoted one senior detective as saying:

“These girls are being passed around and used as meat. To stop this type of crime you need to start talking about it, but everyone’s been too scared to address the ethnicity factor. No one wants to stand up and say that Pakistani guys in some parts of the country are recruiting young white girls and passing them around their relatives for sex, but we need to stop being worried about the racial complication.”

Following the exposure of a similar child sexual abuse ring in Newcastle in 2017, the Labour MP for Rotherham, Sarah Champion, echoed a similar line, that authorities were “not dealing with it”, because they were "afraid to be called a racist”. As recently as 2023, former Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said that the abuse had gone ignored “because of "cultural sensitivity and political correctness”.

This line, or some variant on it, was repeated so often in the media that it soon became the lasting memory for the majority of the British public when remembering Rotherham, Rochdale or any of the other towns and cities exposed by the grooming gangs scandal. The victims had been “sacrificed on the altar of multiculturalism” by an anxious, overly ethnically-sensitive political class which had passed its edict of colourblind tolerance down to the police and social services, terrified that if they accurately described an Asian suspect they’d lose their jobs.

There have been several inquiries in the affected areas in which key people working in local councils, social services, youth charities, and the police were interviewed as to what went wrong. Some of those testimonies do include people saying they were afraid to appear racist if they pushed the issue, or that they thought the Muslim community were meant to be “dealt with” by officials from the same background. But they also reveal far more: under-resourced local services, a culture of institutional misogyny, and police incompetence. None of these factors seem half as attractive to the media as the idea that this was solely down to racial sensitivity, but they should matter to anyone who claims to genuinely care about protecting children.

When being interviewed for an inspection of Rotherham Borough Council following the scandal, one officer had this to say:

“[T]he one thing that we found funny, that had us in stitches, was the idea that those old bunch of politicians could have a problem with political correctness! Ha ha! They couldn’t be further from politically correct. They were bullies, they were sexist.”

This was particularly revealing when it came to the way certain people on the council spoke about the teenage victims themselves. The vast majority were working-class girls from unstable home lives or living in social care. Many of them had been in trouble at school, or previous run-ins with the law for petty crimes. And most had been convinced that their adult abusers were their boyfriends.

They were, in short, not the docile, passive, young woman from a respectable background who functions as an “ideal victim” in the popular imagination. In the words of one Rotherham Detective Sergeant “some of them were worldly-wise and not meek and mild victims’. As a result, many people who were in a position to help the girls genuinely seemed to have no idea that they needed it.

This is revealed over and over again in statements from the inquiries.

One Rotherham councillor, speaking about the victims themselves, said:

“The girls, the way they dress, they don’t look 14-15 years old, the way they make up– they look more adult. They go into clubs, get served in bars, It’s very difficult for me, very modern dress…..”

Someone else, describing the police’s perspective, put it even more boldly:

“The view was that they were little slags.”

This wasn’t exclusive to Rotherham. An inquiry into abuse in Telford heard a police witness say this:

“I think at that time the attitude was that it was a lifestyle choice. These girls had chosen to go with, I don’t know, “bad boys” if you like, because of the excitement of all that, and that may well have been true to some extent. But it wasn’t until later on I think, when attitudes did start to change, that we realised they weren’t actual prostitutes.”

Far from being too politically correct to comment on race, some family members of the victims specifically remember the police bringing it up as a way to dismiss their concerns:

“One mother [...] recalled an officer saying her daughter needed to stop associating with Asian males, (although the officer allegedly used an inappropriate term), as they were not good for her. Another parent told us that, when they raised concerns about their daughter being missing and concerns about older men, the officer said that it was a ‘fashion accessory’ for girls in Rotherham to have an ‘older Asian boyfriend’ and that she would grow out of it.”

Even where there wasn’t overt misogyny, low resources meant that youth services were often pressured to prioritise younger children over teenagers, because they were considered to be the ones who really needed help. As one officer in Rotherham said, the institutional culture often dictated:

“[W]e had to protect the younger children first as they were more vulnerable, and teenagers should be able to make their own decisions. And there was an element of they are choosing to do this, getting into cars in the evening.”

In at least one comment I read, this was framed explicitly in terms of money:

“Resources were an issue: there was a focus on children rather than teenagers. The girls weren’t easy to deal with. They were resource intensive. They were expensive.”

Interviews like these, which directly link child safeguarding failures to lack of funding for social services, were of curiously little interest to our right-wing press or politicians. Perhaps the “political correctness gone mad” narrative was just too exciting, or perhaps, arriving as they did right in the middle of the coalition government’s austerity programme, there was simply very little appetite for the reminder that tight budgets frequently have a human cost.

None of the reports into the failings at Rotherham make for easy reading, but there are some parts which are especially troubling. They suggest to me, at least, that there may have been some members of the South Yorkshire Police who weren’t simply negligent when it came to the gangs, but actively complicit.

I’m not the only person to have had this suspicion. David Greenwood, a solicitor acting on behalf of 65 of the Rotherham victims in 2016, said this after the trial: “We’ve heard evidence in the trial of money and drugs being passed between police and abusers. We’ve heard evidence of behaviour from the police which suggests an element of corruption. I’m sure that at the heart of this there’s money.”

Although none of the official reports state matters this plainly, there are statements that stand out. The council inspection report notes several comments from councillors and social service officers where they tried to register concerns and were told to “leave it” to the police, who were in the midst of an ongoing investigation they couldn’t discuss. But, the report continues:

“[We] were left wondering what these ongoing investigations amounted to. Because, from where victims and some organisations working with them stood, there seemed to be lawlessness in relation to CSE in Rotherham. Perpetrators seemed to face no consequences.”

One victim described being told by a police officer in his car that “nothing good [would] come” of reporting her abuser. After persuading her to drop the charges, she said he pulled the vehicle over, ripped up some paperwork, and dropped her off at a restaurant where suspected perpetrators used to gather.

In the local inquiry into child sexual exploitation, a researcher who had been appointed by the council, conveyed this terrifying story:

“A young girl who had been repeatedly raped had tried to escape her perpetrators but was terrified of reprisals. They had allegedly put all the windows in at the parental home and broken both of her brother's legs 'to send a message'. At that point, the child agreed to make a complaint to the Police. The researcher took her to the police station office [...] Whilst there, the girl received a text from the main perpetrator. He had with him her 11-year old sister. He said repeatedly to her 'your choice…'. The girl did not proceed with the complaint. She disengaged from the pilot and project and is quoted by the researcher as saying 'you can't protect me'. This incident raised questions about how the perpetrator knew where the young woman was and what she was doing.”

Those questions remain unanswered. The Independent Office for Police Conduct undertook 91 investigations into police responses during the Rotherham child abuse scandal. In 2021, it found that eight officers had a case to answer for misconduct and six for gross misconduct. Only two cases resulted in disciplinary hearings. No officers were prosecuted or even sacked.

If you’re looking for an actual taboo around what happened in Rotherham, this feels like a pretty stark example. While untold amounts of mainstream column inches have been devoted to whether the Rotherham police were too politically correct, there has been very little exploration of whether their systemic incompetence ever stretched further into outright corruption.

Sensing the momentum and public anger around the grooming gangs issue, it has become fashionable on the more respectable parts of the British right to call on the Labour government to launch a new inquiry into grooming gangs.

Nigel Farage, leader of the far-right Reform Party, explained to the House of Commons why previous inquiries which looked at the issue, most recently the IICSA, weren’t good enough.

“The scope of that inquiry was like a shotgun, it was to cover a whole range of areas in which children were being abused. What we need, and what we’re calling for, is a rifle shot inquiry. One that looks specifically at to what extent were gangs of Pakistani men raping young white girls.”

This, helpfully, gets to the heart of the far right’s real complaint. No inquiry will satisfy them unless it draws the conclusion that the rape, exploitation and abuse perpetrated by Pakistani men is fundamentally worse in character than the kind committed by white men or against non-white victims.

Some criminologists, like Dr. Ella Cockbain and Dr Waqas Tufail, have argued that this hierarchy was implicitly baked into the “grooming gangs” narrative from the very beginning. The term was always a media buzzword rather than one with a precise definition. This means that reports which have tried to quantify it along ethnic lines have run into severe methodological difficulties, and inevitably ended up counting media headlines. This leads to tautological results. From its very first introduction, part of what made the “grooming gangs” story feel new and modern was the ethnic element. As a result, gangs of white men engaged in similar behaviour might instead get called a prostitution or paedophile ring - that is, if they get press at all. When a gang of mostly white men were convicted for very similar offences in Derby in 2012, the coverage was notably much more muted.

This country has been shamed several times over by child abuse scandals in recent decades. Operation Yewtree, for instance, revealed widespread institutional culpability in covering up sexual abuse against children by the English media personality Jimmy Savile, among several other high-profile entertainers. Savile, just like the Rotherham predators, frequently targeted children in social care.

These crimes and their cover-ups reveal something fundamentally broken in British culture. To say that the problem that needs to be tackled is political correctness, Islam, or immigration rather than patriarchy, classism and an underlying disregard for young people, is to say that only some victims matter.

We know exactly why that idea appeals to racist agitators like Tommy Robinson, but if you actually believe in preventing further atrocities against society’s most vulnerable, it is one you must reject.

Dr. Annie Kelly is a journalist and researcher specialising in anti-feminist and far-right digital cultures. She is the UK correspondent for the QAA Podcast. You can find her on Bluesky here.