Why is God Obsessed with Spanking?

Christian leaders are obsessed with tougher punishment - but why?

Hi,

If you’ve read Webworm for a while, you’ll be aware that I’ve spent a lot of time writing about horrific, corrupt megachurches and the shitty men who lead them.

And in all of this writing, I think some people have this idea that I hate Christians or Christianity. As I explain on today’s Flightless Bird episode (about 7th Day Adventists and Armageddon) I’ve had this slow-burn idea of making a documentary where I go and track down the people I converted to Christianity when I was a teenager, turn up at their door, and go, “Sorry, I fucked up, I was wrong!”

Chaos ensues as I try to un-convert them (and their kids), decades on.

But to clarify a little — I don’t have some blanket disdain for people who have faith. I have disdain for the horrific ways in which religion is used to justify a whole sway of shitty human behaviour. I end up writing about Christianity, because it’s what I know.

So today I wanted to turn today’s newsletter over to Shane Meyer-Holt. He’s a Christian, but he’s — in my humble opinion — one of the good ones. He contributes to a podcast I love (and have appeared on) called In The Shift, which deconstructs the faith I grew up in. He also has his own newsletter, Untethered.

Shane has been looking at this weird obsession so many Christian leaders (see also: world leaders who are “Christian”) have with dishing out harsh justice. Of locking up the troublemakers, or — in some cases — killing them as quickly as possible.

Shane explores where this obsession comes from, and if there’s a better way.

Spoiler: there probably is.

David.

Why are Christians so hell-bent on harsh justice?

by Shane Meyer-Holt

Back in June, Hayden Donnell published an excellent Webworm on the flaws of “tough on crime” policies. In case you missed it, he covered the New Zealand government's plans to “crack down on crime” — including reintroducing boot camps for children, refreshing the three-strikes law and constructing a mega-prison to contain all the future criminals they plan to incarcerate. Of course, they are far from alone in this. The United States is the current world record holder for inmates, and in Australia, kids as young as 10 can be imprisoned.

That all sucks because there’s a ton of evidence that it doesn’t work, and it diverts funding to punishment rather than prevention. At best, it makes us feel safer believing that there are fewer “baddies” out there doing baddie things. At worst, however, it funnels vulnerable people into a justice system geared towards incarceration. In my years working with young people on the margins of society, all too often, I heard them describe the likelihood of their future in a cell with a crushing sense of inevitability.

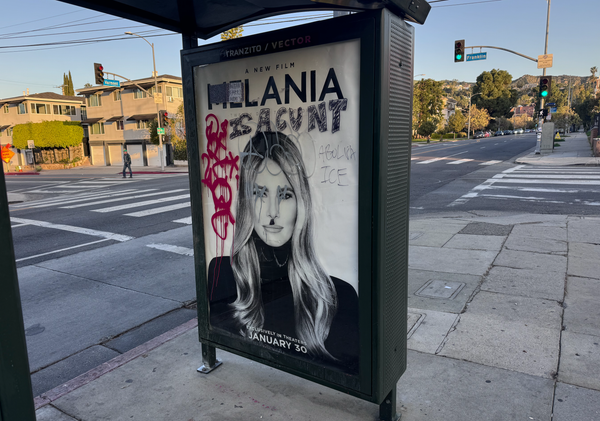

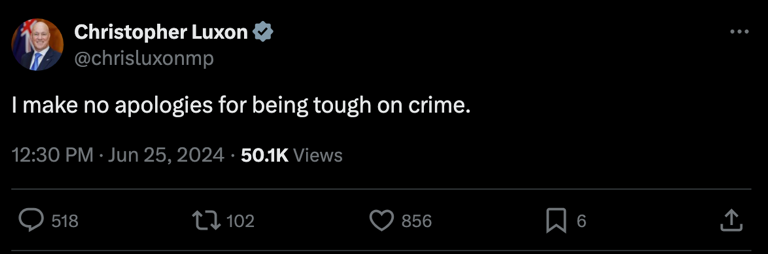

But as a person of faith, what really boggles my mind is that all too often, it’s people who profess to be Christians championing this. In New Zealand, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon and former MP Simon Bridges - both men who have highlighted the importance of their Christian faith - also campaigned on the promise of flexing their judicial biceps.

In Australia, YouTube ranter and former Pentecostal Evangelist Pat Mesiti is exasperated that you’re not even allowed to put an ankle monitor on a child. And over in the United States, Evangelicals disproportionately support state executions. It’s weird. And given they have a not-insignificant voting block behind them, it’s a force worth taking seriously.

This begs the question: why is it that tougher punishments hold such an appeal for so many people whose religion is centred on a man executed by the State? As a group that so often proclaims a spirituality of compassion and kindness, endorsing harsh justice seems to fly in the face of this.

To be honest, I often find myself wondering, “Why are you so mean?”

Then I remember all the years I spent thinking this way. Perhaps a better question is, “Why did this once seem so fair to me?” While there’s undoubtedly a variety of factors at play, I’ve begun to suspect there’s a foundational reason that’s easily overlooked - how Christians see God doing justice.

To understand this, you’ll have to come with me on a short but slightly disorientating journey into an alternate realm.

Many of us who grew up in fundamentalist Christianity were raised with a pretty confusing vision of God that only really made sense in the “MCU” (Munted Christian Universe): God is both loving and holy. Awkwardly, these two traits often came into conflict. Without boring you with the intricacies of how this was theologised, the bottom line is that God really does love everyone, but because “He” is so pure, the divine laws of the universe meant He can’t spend eternity with impure things without them burning up like crepe paper.1

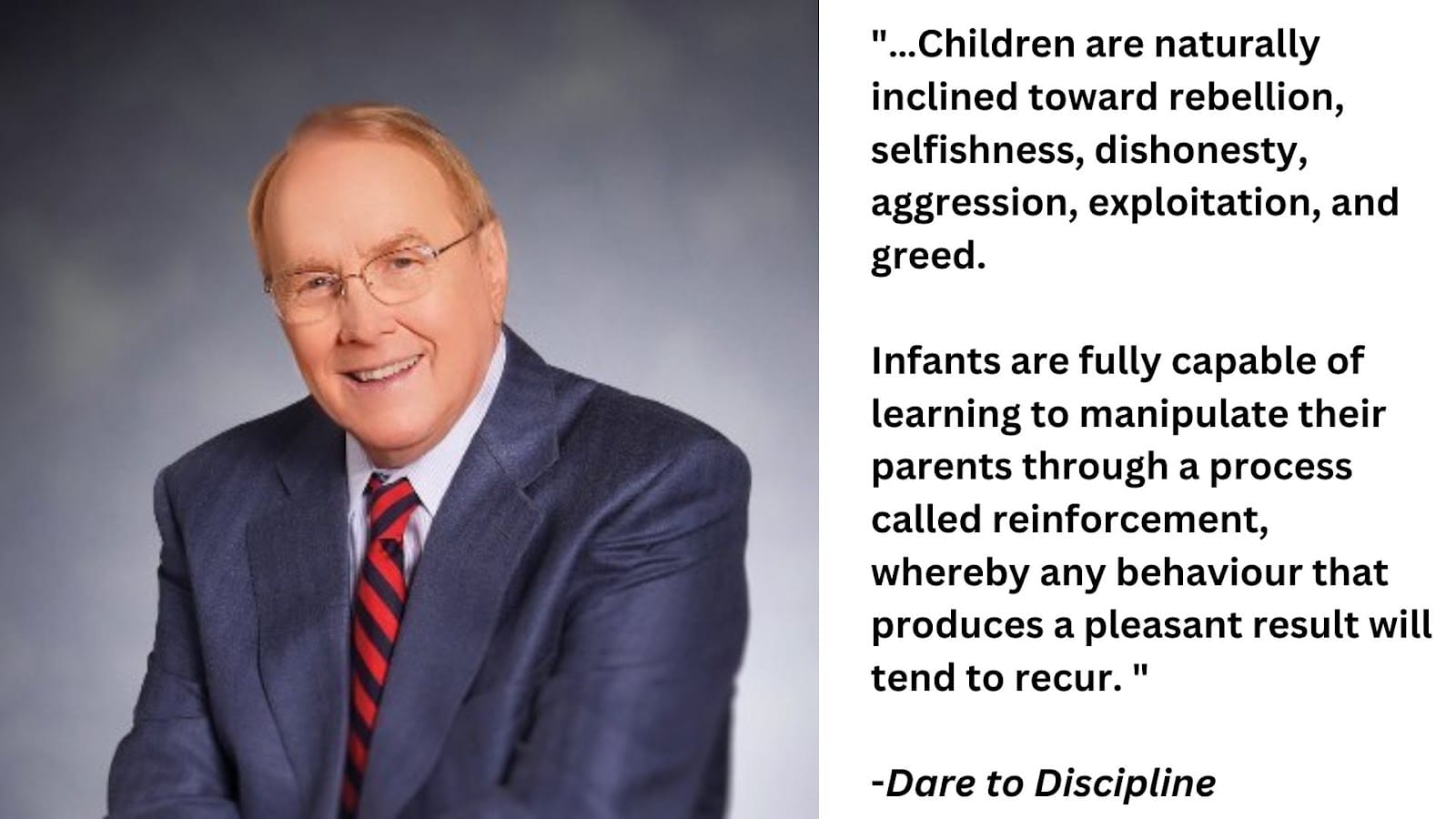

This brings us to “Judgement Day”, where God has to sort out who goes where (sadly, it’s not as good as the second Terminator film). Unfortunately, as spelled out by “parenting expert” Dr James Dobson, babies are all born incontrovertibly evil, so anyone who didn’t make the switch to Team Jesus before they died is stuck on the wrong side of the ledger.

Technically, God doesn’t want anyone to burn for eternity in a fiery hellhole, but he has to be fair. And in the laws of the MCU, being fair has eternal consequences. Come the end of time - with baddies unable to enter a gold-paved paradise - the only other available Real Estate happens to be a conveniently located burning lake of fire. I can tell you from personal experience that convincing children (or adults) that they must believe any of the above is both intolerably cruel and can be very harmful.

But what does this have to do with Christians and mega-prisons? Well, I’m gonna argue that if this is the vision of justice you see God acting out, then that becomes the model you imitate - consciously or otherwise. If God says it’s good and fair, who’s to argue?

The judgement of hell is about delivering consequences to baddies - and the justice system that dominates in the West mimics this. Prison is hell - not just for prisoners - but for the primal logic of punitive justice. If the end goal is punishment, separation, and the illusion of deterrence - then boot camps and mega-prisons are doing a great job.

But surely, at some stage, we should collectively ask, “What’s the point of justice?” and then, “Can we do better?”

The problem is, as Psychologist Richard Beck points out in “Unclean”, punitive justice instinctively feels “right” to us because it taps into one of our most primal impulses - disgust. The disgust mechanism helps our body avoid and expel harmful food, but there are compelling arguments that it drives many of our social habits. Just like the way our body causes us to involuntarily eject that slightly whiffy ham we took a gamble on a few too many days out from Christmas, a justice system that divides the world into insiders and outsiders, then repels and expels perceived “baddies” from society intuitively feels like it’s keeping us safe.

As a self-proclaimed “good kid”, this all made perfect sense to me. A binary world was a simple world and a simple world was a safe world. I remember my nine-year-old self proposing to a friend that the police should arrest all people wearing hoodies because they seemed to feature in all the shoplifting photos at my local grocery store. Surely this would save them a lot of time.

You’ll have gathered by now that central to this view of justice is the focus on isolated individual choices. Systemic issues such as poverty, intergenerational trauma, stability of home environments, and how your culture is embraced in wider society are nowhere to be found.

We’re just isolated people making isolated decisions. And when you’ve never really experienced the dark side of marginalisation, it can all make a lot of sense. Conveniently, this approach means those of us with privilege don’t have to lift a finger to address the many factors that appear to contribute to crime stats more than just “bad choices”.

The big question is whether this is inevitable. Is this just the kind of thing that religion, and Christianity in particular, naturally produces? Some will say religions are hotbeds of intolerance and hate. They can be, of course. No one can deny that those threads are there. But that’s also a fundamentalist view in itself - buying the narrative that there is only one story in a tradition.

Contrary to popular belief, the Bible is not one homogenous text - it’s a wild tapestry of competing voices who all care deeply about what God might be like. Enshrined in the texts are countless arguments about people’s experience of the Divine, what they believe God cares about, and how justice should work on the ground.

When Jesus says, “You have heard it said… but I say…” he’s entering into that conversation - this is how wisdom traditions work! People of faith have always had to make decisions about what threads of their tradition they’ll hold on to. They just often pretend they don’t.

What’s remarkable is that, despite how prevalent the relatively recent punitive vision of eternal torment is, it is far from the only option in the Christian tradition. There’s a long line of prophets — from Jesus to St Francis of Assisi to Desmond Tutu who didn’t see a God obsessed with spanking but one who cared deeply about ongoing care and the prevention of harm.

Here, the end goal is less about individual destinations as it is about the unfucking up of all of the deeply fucked up things in this world. God’s judgement is about calling out harm, and inviting creation towards the redemption and renewal of all things. This includes restoring fractured communities through truth-telling, reparation and reconciliation. Theologians such as Kathryn Keller, Jürgen Moltmann and Miroslav Volf have argued that the only vision of Divine judgement worth holding on to is a restorative one.2 “Heaven” is not up there but down here. And it is not an apartheid state but a healed and thriving community of all creation.

For many of us, this vision of justice is a wellspring of hope - a difficult challenge to the understandable knee-jerk reaction of vengeance. And as unpalatable as it might appear, sometimes those who need a way back to community, back to humanity, are those who have caused harm.

I’m not arguing for “soft on crime”. I’m arguing for the difficult work of seeking restoration, even though it won’t always be fully possible. I’m excruciatingly aware of those who have suffered horrors at the hands of others here, but unless we have it as a goal, we risk seeing everyone who crosses a certain line as a subhuman write-off who deserves the minimum of care and effort.

Of course, there are very good reasons not to believe in this. First of all, it’s much harder than just “disappearing” faceless baddies. Doing the work of truth-telling, listening deeply to the experience of victims, finding ways of building trust and ensuring repentance is real without endangering vulnerable people - these are all very difficult things.

Tutu, whose theology of restorative justice shaped his work as Chair of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission says:

“Forgiving and being reconciled to our enemies or our loved ones are not about pretending that things are other than they are. It is not about patting one another on the back and turning a blind eye to the wrong. True reconciliation exposes the awfulness, the abuse, the hurt, the truth. It could even sometimes make things worse. It is a risky undertaking but in the end it is worthwhile, because in the end only an honest confrontation with reality can bring real healing. Superficial reconciliation can bring only superficial healing.”

This also means telling the truth not just about perpetrators but about the systems in which they exist. Fixing some of the systemic issues, such as the lack of secure housing, accessible therapy to process trauma, and a liveable social security net, might really cost us something.

I’d argue nowhere near as much as it costs to house and feed a prisoner for 40 years, but still…

Christianity can function as a religion that peddles fear with totalitarian fervour. Or, it can offer a radical vision of kindness that invites us into challenging but beautiful possibilities. People of faith can believe in the God of simple solutions or the God of difficult compassion, who fiercely takes the side of victims and wants a way back for those who have committed harm. A life and afterlife of vengeance or the persistent hope of reconnection.

Could a kinder vision of the afterlife inspire Christians to fight for more hopeful possibilities here? Could it help us all dream of a better kind of justice? Could convince us we can do better than locking up 10-year-olds?

In my case, spending time with kids on the wrong side of the law made me choose sides. It made me choose Gods. I chose the one who talks about the last being first and stops everything to find the lost sheep. That God doesn’t look anything like the God of James Dobson or Donald Trump, but might look a bit more like Jesus.3

-Shane Meyer-Holt

Shane works at a curious and queer-affirming church in Melbourne called Fitzroy North Community Church. It’s not fancy but very kind. He also chips in on an excellent podcast called “In the Shift.”

*At which point you might ask, “If they were divine laws, then wouldn’t that mean God made them and could change them?” to which I can only shrug and say, “See my first point about things that only make sense in the MCU.” ↩

The older I get, the less concerned I am with whether or not I believe this stuff is “true” in any provable sense. Despite the extreme unlikeliness of an afterlife, I find myself hoping for it - that something this beautiful might be possible, either side of death. I’m compelled by a deep desire for love and consciousness to endure beyond life. However that might look, I want the experience to carry on. The other reason is a demand for justice. The idea that some people get to live and die as prosperous tyrants without ever facing the damage they’ve done, while others are born and die in refugee camps without ever having the opportunity for a life of freedom is just too much for me to bear. To keep fighting for justice now, it helps me to believe it might not all just burn up when the sun explodes. ↩

For the record there are heaps of Christians who have chosen this path. In Australia, Common Grace is campaigning to Raise the Age of criminal responsibility. Youth advocate AJ Hendry from Kick Back Make Change does marvellous work advocating for young people in Aotearoa, and among many others, Prison Fellowship fights for prison reform in the United States. ↩