Why Webworm Has Left Substack

Webworm has left Substack for Ghost. Here are all the reasons why.

Hi,

Welcome to Webworm, no longer on Substack. Instead, Webworm is powered by the open source "Ghost".

In short: Nothing dramatic is changing for you, wonderful member of the Webworm community. My investigations and oddities will continue to arrive in your inbox (and on the website, www.webworm.co) as they have for the last 5 years + 4 months.

But, I have moved off Substack entirely — using another technology (called “Ghost”, oooh, spooky!) to deliver my writing to you.

Why? Well, I will try to make it simple and short. What follows is the last newsletter I sent out via Substack.

Oh, and if you're new here for any reason - you can sign up here:

If you're currently reading for free, and you believe in what Webworm stands for, consider signing up as a paid Webworm member.

And there's a Tip Jar, if you want to contribute to Webworm's legal defence fund:

The Camel’s Back

Back in January of 2024, I sent out a newsletter called “When Good Dogs Do Bad Things”. In it, I explained how, as well as hosting newsletters like Webworm, Substack also hosted newsletters by some Nazis.

Not borderline alt-right types, but full-blown Nazis.

Substack has an incredibly hands-off approach to moderation, and at first wasn’t going to do anything. Then, after pressure from writers (and readers) like me who weren’t Nazis, Substack deleted a bunch of them, deciding they did violate one of their T&C’s by including “credible threats of physical harm”.

Back then, I decided to stay on Substack — hoping things would get better. I have had open dialogue with their founder, Hamish McKenzie, which I found somewhat reassuring.

I hoped things would get better.

They didn’t.

As Webworm crept up some of Substack’s “Rising in Culture” lists’, newsletters touting harmful anti-trans rhetoric, conspiracy theories, and health misinformation also crept up (way higher than Webworm), aided by Substack’s algorithm.

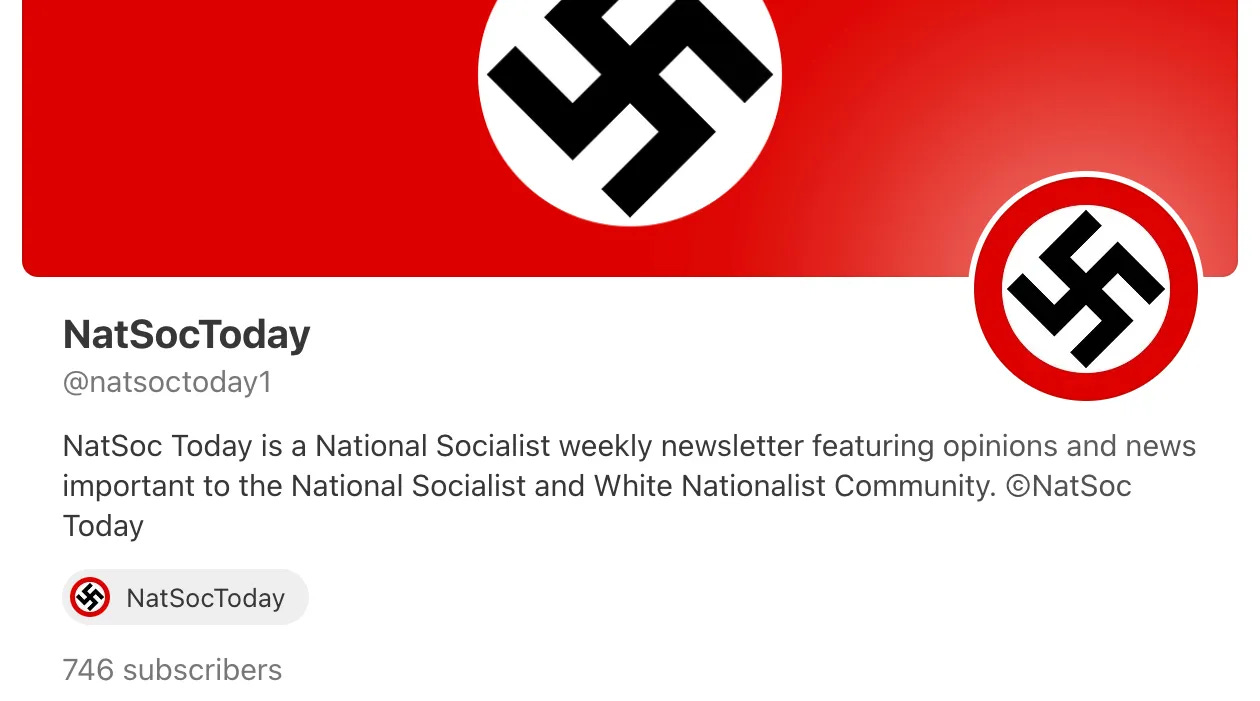

Then, last month, Substack sent out a push notification to some users of the Substack app encouraging them to subscribe to a Nazi newsletter. Like, full-Nazi stuff. Not subtle:

Not only were they still allowing Nazis to publish using their technology, but their App was telling people about it. In a positive way.

As Taylor Lorenz reported on July 29:

Substack sent a push alert encouraging users to subscribe to a Nazi newsletter that claimed Jewish people are a sickness and that we must eradicate minorities to build a “White homeland.”

NatSocToday describes itself as “a weekly newsletter featuring opinions and news important to the National Socialist and White Nationalist Community.”

So that happened, meaning it could happen to you — my reader — too.

The Straw

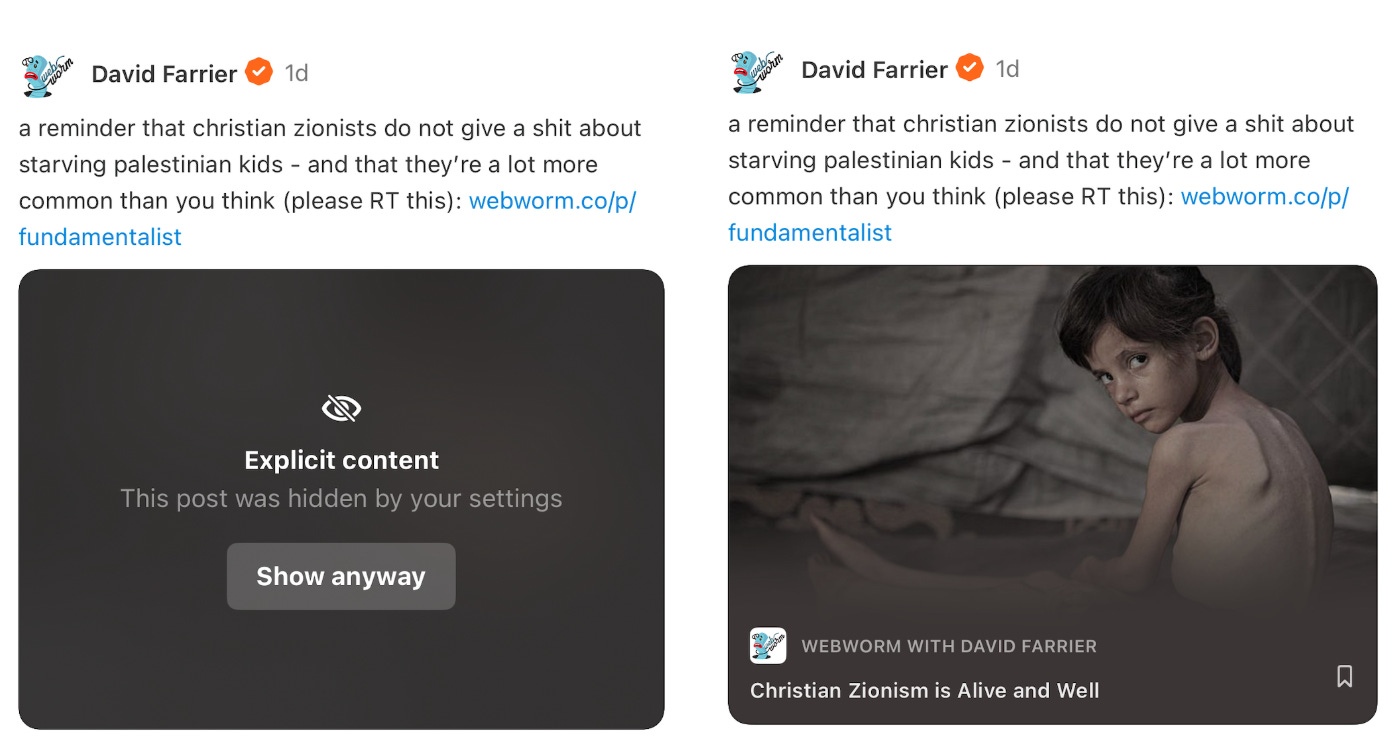

That same month, I used the Substack App to post a message about the genocide in Gaza, which included a photo of a starving child. The App censored it.

Something about Nazis being actively pushed to some Substack users, whilst a photo of a starving child got auto-censored, made me snap. As in I yelled “OH FUCK OFF”, very loudly, to myself, in my one-bedroom apartment.

Since I yelled that profanity to myself, some deep dives by some other journalists turned up. On August 7, Marisa Kabas & Jonathan Katz wrote:

Substack founder Hamish McKenzie used an official podcast to promote Richard Hanania – an openly racist former writer for white nationalist blogs like Richard Spencer’s alternativeright.com, who had shifted from calling for the sterilization of “low IQ” minority groups to more strategically calling for more policing of Black neighborhoods and the gutting of the Civil Rights Act. The official Substack blog, meanwhile, had promoted Darryl Cooper, a podcaster who, as I noted in my Atlantic piece, had argued that the United States should have joined the Nazi Axis in World War II.

Earlier on July 31, Noah Lanard wrote a piece for Mother Jones titled “How a Nazi-Obsessed Amateur Historian Went From Obscurity to the Top of Substack.”

You get the idea.

Putting it bluntly: Nazis (and homophobes, and anti-trans folk, and conspiracy theorists) have always existed on the internet, and always will. But being in a place that not only actively hosts them, but promotes them through algorithms and talking about them, is a deal breaker for me.

Begging the Question: Why Have I Stayed Until Now?

Over the last year or so, since I wrote “When Good Dogs Do Bad Things”, various people have gotten in touch demanding I leave Substack immediately.

I understand their perspective, but wanted to quickly explain why I have stuck with Substack until now. I am not saying it was the correct decision, but I hope it informs where my head has been at.

I think there’s this idea that moving Webworm from Substack to another platform is as easy as moving from Twitter to Bluesky. But there have been a lot of other considerations that came into this move:

- Over the last five years, Webworm has turned into a fulltime job. A job that I love. I didn’t want to make a kneejerk move and mess that all up — for me, for the guest writers I pay, or for you, my reader.

- For the last few years, I have been a part of Substack’s legal defence programme, where under certain circumstances they will defend me in court, at no cost to me. When writing critically about megachurches and literal billionaires like Nick Mowbray, as a solo journalist without the backing of a newsroom’s legal council, this significantly mitigates risk.

- I have been in touch with Substack’s CEO over the last year, directly voicing my concerns and hoping pressure from writers would help keep them on track. “Change from the inside” was my hope.

- Substack’s algorithm. Webworm is powered by lots of small individual payments from my readers. And while people sign up, they also leave — which is why some months Webworm is shrinking. But, sometimes Webworm grows and bounces back — and a big part of that growth is due to Substack’s algorithm. It lets people who don’t know about me or Webworm find it, and this makes up for any subscriber “churn”. In the same way that Nazi push motivation went out, some people are getting told about Webworm. That is a powerful tool for Webworm’s survival.

- There are writers on Substack that I admire, and whose work I love: Parker Molloy and Taylor Lorenz come to mind. It’s not all Nazis out there!

- CEO Hamish McKenzie is a friend. I started writing on Substack when it had just started — and I get quick, direct tech support from them. A practical example: One time someone accidentally subscribed for $36,000 (there is an option when you become a paying member to “choose” an amount). The reader emailed me in total panic, and of course I refunded them $36,000. But Substack had already taken their 10% cut ($3,600) and Stripe had taken an additional $972.30 in processing fees. Stripe refused to refund a cent. But Substack, no questions asked, did — refunding the $3600 immediately.

- The Substack App can be slick and beautiful — and there are some readers, especially younger ones, that only read Webworm on the App. I also have enjoyed the Substack chat, where we’ve done regular shares of our pet photos. While silly, it’s fun!

- I am scared of change.

- Over the last five years, I have gotten used to writing directly into the Substack interface; It was a ritual and I was scared of changing the ritual.

- I am scared of change.

I Am No Longer Scared of Change

It was a year ago when I first spoke to Ghost, an open-source alternative to Substack. They do not host Nazis.

As I kept running points 1 thru 10 in my head over the last year, I also kept talking to the people that run Ghost. I have gotten to know them. I trust them.

Over the last few weeks we’ve been doing some technical tomfoolery behind the scenes, and over the weekend, Webworm will migrate so that it’s fully powered by the nonprofit, open-source publishing platform Ghost.

To be clear — the next edition of Webworm will be delivered as per usual to your inbox.

All your subscriber information is saved, nothing has changed. If you’re paying for Webworm, you don’t need to update payment information — it’s all stayed the same.

Any stress has all been at my end, not yours!

What Is Good About This Move?

I have written at length about the impossibility of living an ethically perfect life (focussing on me being a milk guzzler). But making this change is one very logical thing I can do.

In bullet point form:

- For you, my reader, nothing really changes. This is good!

- I am no longer giving 10% of what I earn to Substack, a company I no longer have faith in to do the right thing.

- Ghost has a much more aligned view on what free speech means. I have talked to them at length about this, and feel confident in their moderation approach. And if they ever start hosting Nazis? Well, because Ghost is open source, I can set it up so I host it all myself one day. I can do this relatively easily as I will be entirely free from Substack.

- I am no longer locked into Substack’s world. I have realised a lot of the “positives” I listed earlier are also a kind of curse. The slick app? That just made it harder for me to leave. My reliance on the algorithm to get me new readers? That also made me feel locked in. In short — while it’s nice to have certain Substack features, you also become reliant on them — which is exactly what they want.

- I have little doubt that at some stage, Substack will pull the rug out. Substack can be generous now while funded by VCs — but eventually those VCs will exit, and Substack will be under more pressure to squeeze writers, and readers. Maybe they’ll force ads in. Maybe they’ll change prices. My point is, if they pull the rug, it’s a hard landing. This is what newsrooms discovered the hard way about relying on social media platforms for their distribution. And what they’re learning now about Google.

- With that in mind — the longer I keep using their tech, the harder it will be to leave. So I am leaving now.

- Substack has made itself a social media network, and we’ve seen how that goes Every. Single. Time. I think my anxiety about making this move is proof that yes, Substack is too much in control of how I do things. In making this move to Ghost, and you sticking with me, this anxiety leaves.

Why I Need You Now More Than Ever

While I am absolutely backing my decision, there are a few things that I am nervous of — and paradoxically the first thing is the reason I decided to make the change in the first place.

In leaving Substack, I lose their algorithm — an algorithm that allowed me to find new readers. Yes, the same algorithm that allows Nazis to find new readers.

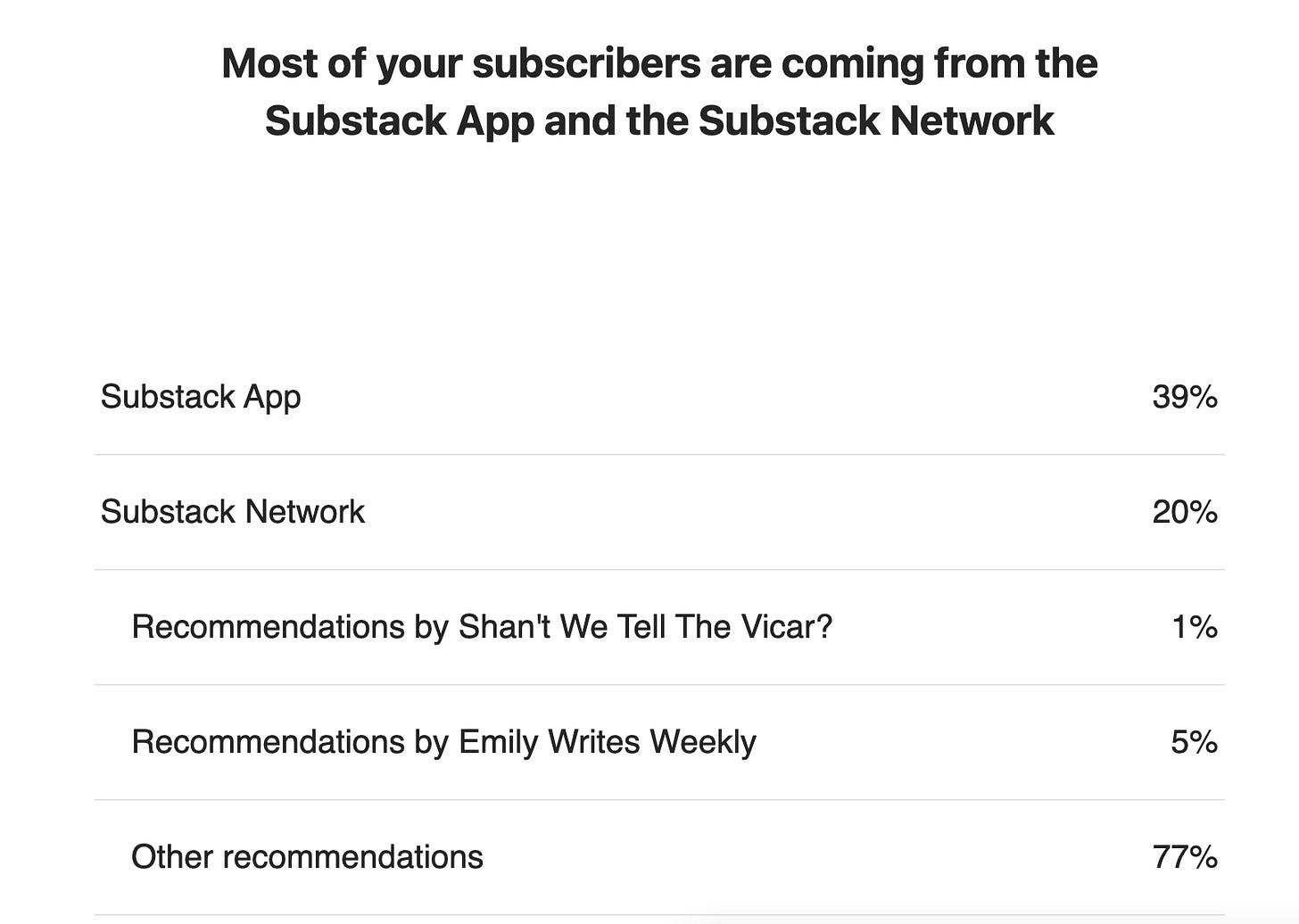

This is an example of a “subscriber summary” Substack delivered for me last month, showing that nearly 40% (that’s close to half!) of new Webworm readers were discovering me because of the Substack App and the Substack social network:

I lose all that on Ghost.

Secondly, I am no longer part of Substack’s legal defence program. If I get sued, that’s all on me, an individual.

I am fortunate and lucky enough that over the last five years — thanks to paying subscribers — I have been able to save a small war chest for such things. But that shit goes quickly. And I need to keep on top of it (it’s already been used on occasion to engage lawyers to deal with the various cease & desists Webworm gets).

And so, more than ever, I am going to rely on YOU. Your subscription is now more important than ever, and so is telling other people about Webworm.

If you already pay for Webworm: Thank you. Please just know that Substack now has nothing to do with it.

If you don’t pay for Webworm — consider signing up as a full, paid member:

My usual thing still stands: Only ever pay for Webworm if it causes you zero financial hardship. Screw paying for this if you’re stretched. If you are a student, or on a pension, or any kind of benefit, or just having a hard time — email me what’s going on and I will comp you a full paid membership: davidfarrier@protonmail.com.

Just To Repeat Myself A Little: What Changes, Then?

As I said, very little.

- The most “extreme” thing? You will have to login again if you want to comment under my next piece. It’ll all be very user friendly and obvious. You’ll see for yourself when you hit “comment” in the next edition of Webworm.

- New Webworms will no longer appear in the Substack App. It’ll be in your email inbox (as per usual, check your spam if it’s not showing up) and at www.webworm.co (as per usual, too).

That’s not to say a shitload of work hasn’t gone into this change (and more over the weekend) and there may be some teething issues. If so — email me here: davidfarrier@protonmail.com.

I won’t be far away, and am here for you, like you’ve been here for me.

God, I said this would be short. It’s gone long. Thanks for your support,

David.

PS: I wanted to end with a conversation I had with the founder of Techdirt, Mike Masnick. We’d been talking about the Streisand Effect — and I realised he’d been writing about the internet, free speech and legal craziness since the World Wide Web arrived in the 90s. So I started to talk to him about Substack and the decision I’d made.

Mike mirrors where my head is at perfectly:

When Substack first came about, I was actually really excited by it. I had talked to the founders before they’d even launched when they were still thinking about the idea.

I had been introduced to him through another New Zealand person who I was friends with. Turns out I know a lot of people from New Zealand. I don't know how that happened!

I had a lot of hope for them — and I now am very worried about where they're heading and what they're doing.

I think they originally structured themselves in a way that was very much about “user empowerment” and “run your own newsletter” and “we have a built-in business model” and “we’re empowering writers” — and that was very exciting to me.

I think there are a couple of things where they made some poor decisions recently. One was that as they were trying to raise money, they realized that they needed to add these other social components, which were more about sort of creating lock-in.

Part of the original promise of Substack was that writers own the relationship with their readers. You can export everything and leave and take it with you. But they’ve really started to add a bunch of features that are really sort of designed to keep you there.

That is a big concern. And I think it goes against the original ethos… but I think it makes sense given the incentive structure that they faced as a venture backed company.

The second thing was that they presented themselves as being this sort of free speech platform. And look, I’ve spent 25 years talking about the importance of free-speech and trying to get across how important free speech is.

But I think they misunderstood what free speech really means — and free speech includes the right to associate and not associate with certain individuals. And they sort of took it to mean, “We must allow all speech, no matter what.”

But when confronted with this, Chris [Chris Best, Substack CEO] basically said, “We don't care. Like, anyone can be on our platform.”

And when it was presented to them even further, that there were outright neo-Nazis using the platform, like, “How do you feel about that?” they were kind of, “Well, you know, it would go against free speech to take it down.”

Which is not true, right? No-one’s saying that Nazis have no right to speak — but you can say, “They can't speak in my living room. This is my house and I can decide.”

That is true of Substack: Substack is a private company. They get to decide who uses their thing. That’s not saying Nazis have nowhere to speak! If they wanna go speak, they can go set up their own website!

That you are saying, “We’re not going to moderate that” also does a second thing, which is that it paints a giant sign on Substack itself and says “Nazi-friendly.” And then it sort of gets taken over. And as we’re speaking today — I don't know if you saw the news this morning — Substack did a push notification in their app for an article from a blatantly pro-Nazi Substack.

And so a bunch of people once again are saying, “Huh, Substack seems not just welcoming to Nazis, but now they’re actively promoting Nazis.”

And so I think they’re wrong about free speech. I don’t think they actually understand what free speech is, because while it sounds good to say, “We’ll let anything go”, that means you’re actually probably crowding out a bunch of people.

Because while some people will stay, a lot of people are going to say, “Well, I don’t wanna put my newsletter on ‘the Nazi site’ — and so that crowds out other kinds of speech.”